Editor's Note: This article references racial slurs and offensive language.

Ever since the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol, Americans and the world have tried to make sense of the violent insurrection that horrified television viewers.

The past month has been a time of reckoning with the growth of white supremacy and other hate groups that have been growing largely unopposed. Americans have also seen a rise in violence toward Asian Americans. On Feb. 25, a 36-year-old Asian man was stabbed in an unprovoked attack in New York City’s Chinatown. In a little under a year, StopAAPIHate has seen a 1,900% increase in hate crimes against Asian Americans in the city, totaling 2,800 separate incidents including both verbal and physical assaults.

President Joe Biden addressed these problems during his inaugural address, urging listeners to combat this national division through unity.

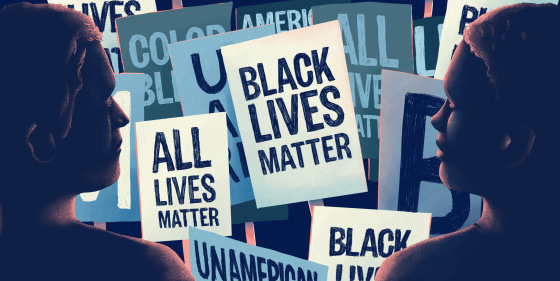

From this rift, reactionary terms and phrases like “socialist” and “all lives matter” have emerged, meant to further fuel hatred. TODAY interviewed former neo-Nazi turned activist Christian Picciolini and author, social justice poet and public speaker Theo Wilson to help unravel the meaning behind these inflammatory phrases — and, more importantly, explain how to respond when they are used.

“Unpatriotic”

As a former member of a white nationalist hate group, Picciolini said he is strongly opposed to any instance where patriotism is used to promote racist ideals.

“Groups like QAnon, and certainly even white supremacist groups, are all kind of banding together behind this false notion of patriotism,” said Picciolini, 47, of Chicago. “Their notion of patriotism is anti-Semitic; it is often based on conspiracy theories on race. These groups love to hide behind things like the American flag and free speech because those are things that should be very hard to argue against.”

Picciolini told TODAY that white nationalist music is what ultimately helped radicalize him through what he now sees as a false patriotism narrative. During the ‘80s and ‘90s, he was deeply entrenched in the first neo-Nazi skinhead group: the Chicago Area SkinHeads. A shaved head and swastika tattoos across his body painted the portrait of a different man who was spewing hate rather than breaking it. In fact, he formed two separate bands, White American Youth and later Final Solution.

But today, as the founder of the Free Radicals Project in 2017, Picciolini said racist ideologies are more “palatable to the mainstream” due to a conscious decision on the part of former KKK leaders David Duke and the late Tom Metzger to soften the language around their mission. They realized that since many Americans had relatives who fought against Nazi Germany in World War II, “swastikas weren’t going to attract the average American white racist.”

How to respond: Picciolini said when he is accused of being unpatriotic, he avoids a confrontation, adding he doesn’t need to prove his dedication to the United States to anyone. He condemned it as “racial gaslighting,” adding that real unpatriotism is “trying to take away the voice of a marginalized group or keeping democracy from progress.”

“I have Black friends.”

Wilson said this phrase is used to deflect the possibility of even having implicit biases through the notion that being friends with someone who is Black makes one immune to committing racist acts.

But Wilson, 39, of Aurora, Colorado, has heard this excuse too many times. He suggests asking the following to anyone using this phrase: “If you really have Black friends, why aren't you listening to them? If you have Black friends, care about their lives. If you got Black friends, you should be saying, ‘Black Lives Matter.’ Or don't your friends' lives matter?”

In 2011, Wilson lost his childhood friend Alonzo Ashley, 29, after he was tasered multiple times by the Denver police in a zoo altercation. His latest TEDxMileHigh talk eulogized his death along with that of George Floyd and others.

I try to bring the conversation to a place of commonality. And despite how ugly, you know, some people’s beliefs are, they still probably have children or, you know, want to be healthy or need a job, things like that.

Christian Picciolini

Eight years earlier, Wilson was almost sure that he was going to join the list of Black people who have been killed by police officers. The summer of his college graduation, Wilson was beaten by Denver police. The event is still traumatic for Wilson, who said he thought he was going to die.

“There's nothing like being a police brutality survivor, like Eric Garner's death knocked me down,” Wilson said. “It wounded me because how he got beat up was very similar to how I got beat up, and the survivor's guilt weighs 10 tons … You don't know why I lived and why this guy died.”

How to respond: Wilson said this phrase shows the danger of thinking that racism is binary: Either you are racist or not. He encourages people to think of it as a scale and help others come to terms with the fact that everyone has biases that can cloud judgment or opinions.

“I turn it back on myself,” he said, “like am I an ally to women? Yes. Am I still working through some toxicity? Yeah, they're both true, see? Your willingness to be called on it is the thing that makes you an ally or not.”

“All lives matter.” “Blue lives matter.”

Picciolini and Wilson agreed that both phrases were intentionally manufactured to be in direct opposition to the 2013 hashtag “Black Lives Matter” and the greater movement behind the rallying cry. Picciolini told TODAY that 30 years ago, he would likely have been leading the “All lives matter” marches.

“They're using that just to maintain power, to push back against another civil rights movement that is making progress,” Picciolini said. “Fundamentally, all lives do not matter to them.”

You wouldn’t say to somebody who’s suffering with breast cancer, "All diseases matter."

Theo Wilson

Wilson likes to use two analogies to illustrate how counterintuitive it is to say “All lives matter” in defiance of “Black Lives Matter.” He said that if his house were aflame and he yelled to you to call the fire department, no one would ever refuse and say, “All houses matter.”

“I know houses matter, that's why I need help. My house is on fire, what's wrong with you?” Wilson said. “And the best rebuttal to ‘All lives matter’ is you wouldn’t say to somebody who’s suffering with breast cancer, ‘All diseases matter.’ You just wouldn’t say that.”

And Wilson is more confused by "Blue lives matter."

“When does a blue life begin?” he said. “If blue lives matter, tell that to Black cops out of uniform. Period. They will tell you real quick, ‘I'm not a blue life without this badge.”’

How to respond: Wilson suggested placing the onus on the other person to explain their position. Asking probing questions can help to see if they truly understand the message behind the phrase.

“Ask them to drill down into what Blue Lives Matter means,” Wilson said. “When you say ‘All lives matter,’ what do you mean? Put it back on them … Because most people when they say that kind of stuff haven't examined it past the point of arguing on social media. It does it in a polite way that says you should be able to defend how you feel.”

What people miss is the opportunity that America can be great if it faces its past.

Theo Wilson

If the person saying it is in your social circle and you feel comfortable, Wilson said it can be extremely effective to call them out in front of the group in a constructive manner.

"Yo bro, that's not how we do it; that's not how we do it, man,” Wilson said as an example. “Because if you don’t, you permission the space for more. And by the time you permission the space for more, it’s just a catastrophe.”

“I marched in the ‘60s.”

In light of the 2020 protests that erupted across U.S. cities like Minneapolis, Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio, this sentiment was used in defense of choosing not to protest. Wilson acknowledged that while people may have marched in the 1960s, not supporting the Black Lives Matter movement based on the thought that “Dr. King would have a problem with the statement” is a flawed belief.

“Black Lives Matter has always been what we're saying,” Wilson said. “It’s literally always been what we're saying to them — not saying we matter more, but just matter at all.”

How to respond: Picciolini cautions against trying to talk to strangers in a large group since they are unlikely to defy the group mentality. Keeping it to a one-on-one encounter often leads to a better result.

“I don't argue with them,” he said. “I try to bring the conversation to a place of commonality. And despite how ugly, you know, some people’s beliefs are, they still probably have children or, you know, want to be healthy or need a job, things like that.”

In the event a discussion devolves into a shouting match, Picciolini says having a reference point of commonality to circle back to is crucial, although he emphasized this does not mean agreeing with them ideologically. But, in seeing what people care about, Picciolini said you should try to see the “potholes” in someone’s life that need mending.

He considers potholes to be problems people must handle in their lives that detour them into fringe ideologies. He has found that often issues of trauma, abuse, poverty or even privilege can lead someone to search for belonging in hate groups. Picciolini said his pothole was an eroding relationship with his parents who were always working.

“Liberal media”

On its face, the term suggests that a media outlet is biased toward Democratic ideals, but Picciolini argues the origin of this term is firmly rooted in the Third Reich and the rise of the Nazi Party during World War II. It derives from the German word “Lügenpresse,” or “lying press.”

Adolf Hitler challenged the credibility of Jewish journalists in Germany to stir his followers to question and, ultimately, despise the media. Picciolini said the term “liberal media” is simply a modern adaptation to have people doubt accredited news outlets.

“Media companies are being painted fake news and the lying press in the exact same way,” Picciolini said. “That's dangerous because really, their mandate is to tell the truth, to really dig until you can find it.”

How to respond: In Wilson’s experience of combating sentiments that mainstream news outlets are “fake, liberal media,” he said the best tactic is to “stay on the facts.” That means seeking out primary sources, including court documents or videos, and steering away from proselytizing pundits.

“Drill down to the facts,” Wilson said. “Have you read ‘The 1619 Project’ or have you just listened to (Sean) Hannity talk about it? Primary source journalism, primary source research in the age of the internet is gold.”

“Systemic racism doesn’t exist.”

Wilson said the reason so many people decry the existence of systemic racism is because they are looking for “explicit laws that say Black people can’t, and white people can.” He said that one of the last explicit forms of racism dissolved with the unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decision that approved of a busing program to help the process of racial integration in schools.

It's a privilege not to have to figure out how you affect other people … This whole critique of political correctness, a lot of it is based on the fact that you just don't like having to play by other people's rules.

Theo Wilson

These days, according to Wilson, systemic racism exists in the interpretation of the law, when someone’s intentional or even unintentional biases can determine how a law is enforced. He drew an example from Shawn Rochester’s book “The Black Tax: The Cost of Being Black in America,” in which he details an experiment conducted by consulting firm Nextions to demonstrate implicit biases in the workplace.

The team drafted a legal memo with 22 errors and submitted it for review by 53 partners from 22 law firms. About half were told it was written by a Black man and the others, by a white man of the same name: Thomas Meyer.

Results showed that when the reviewers thought they were reading a memo written by a Black man, they found most spelling errors, scoring him a 3.2 out of five and noted he needed a lot of work. However, when they were told a white man drafted the memo, they found only three of the seven spelling mistakes and scored it a 4.1 out of five, praising him for his analytical skills.

“And that translates to dollars and cents,” Wilson said.

How to respond: Wilson suggested that if someone declares systemic racism doesn’t exist, providing specific examples of its existence in the interpretation of the law can help. For instance, Wilson pointed to a 1973 lawsuit filed by the Justice Department in which former President Donald Trump’s real estate company was proven to have violated the Fair Housing Act of 1968 by discriminating against potential Black renters.

“What people miss is the opportunity that America can be great if it faces its past,” he said. “It's like therapy. You're never going to say your childhood don't matter. America has a screwed-up childhood.”

“It was one joke.” “You’re too soft.”

Both phrases often trail closely behind an intolerant joke or statement as a way to minimize their impact. Wilson said reducing a disparaging comment or stereotype to a joke is the first step in normalizing these intolerant ideas that can lead to violence toward a minority group.

“It's a privilege not to have to figure out how you affect other people,” Wilson said. “For the last 500 years, Black and brown folks had to step off the sidewalk when a white child walked by. This whole critique of political correctness, a lot of it is based on the fact that you just don't like having to play by other people's rules.”

He added that in the time of Black slavery in America, use of the N-word and jokes were closely followed by violence. Curbing offensive jokes is not an indictment on free speech but rather an effort to “stop the chain of violence here.” His concern comes as the Southern Poverty Law Center reported the number of hate groups in the U.S. has doubled since 2016.

“These are the same people who will be like, ‘Oh the left … you guys are weak,’” Wilson said. “That's fine. But you can't accept the reality of losing this election.”

How to respond: Picciolini said the hardest part is for someone to admit to themselves that they possess biases about certain races, genders or religions. Through his experience, Picciolini encourages people to stand up — but in a nonaggressive way — that is constructive rather than more “cancel culture.” He added that people cannot grow when mistakes cannot be made.

“We are all in a learning process,” he said. “And people are accountable for their actions, but at the same time, we cannot ask them to stop hating and then have no place for them once they do.”

Ultimately, Picciolini said the nation at large must also finally acknowledge its “historical potholes” — and that starts with accountability.