When Albert Einstein introduced his theory of general relativity in 1915, it changed the way we viewed the universe. His gravitational model showed how Newtonian gravity, which had dominated astronomy and physics for more than three centuries, was merely an approximation of a more subtle and elegant model.

Einstein showed us that gravity is not a mere force but is rather the foundation of cosmic structure. Gravity, Einstein said, defined the structure of space and time itself.

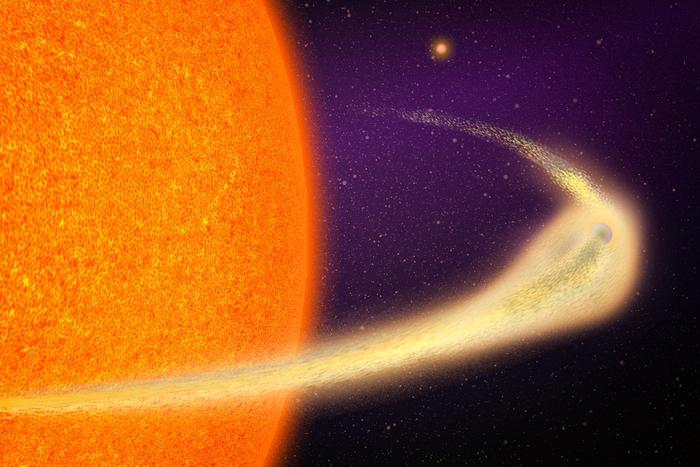

But in the past century, we have learned far more about the cosmos than even Einstein could have imagined. Some of our observations, such as gravitational lensing clearly confirm general relativity, but others seem to poke holes in the model. The rotational motion of galaxies doesn’t match the predictions of gravity alone, leading astronomers to introduce dark matter.