The U.S. Supreme Court has struck down a law used by Florida and other states that set a strict cut-off, based on IQ test scores, to determine eligibility for the death penalty.

In the wake of the court's earlier ruling that the states may not execute the "mentally retarded," Florida determined that the dividing line would be an IQ of 70.

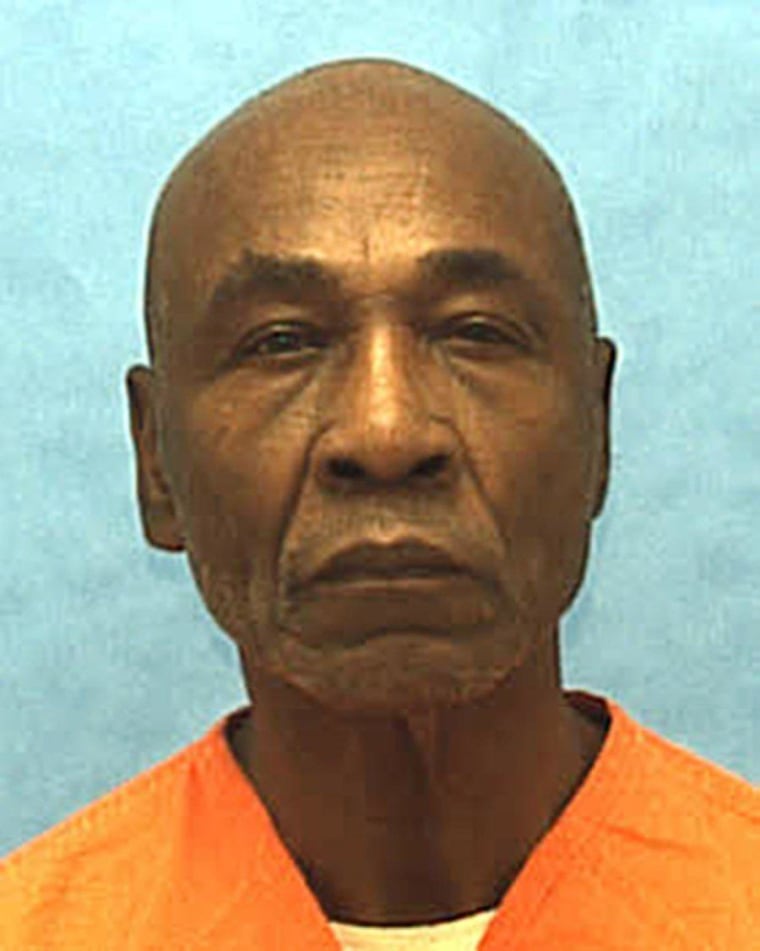

The defendant in the case at the center of Tuesday's ruling, a convicted murderer named Freddie Lee Hall, had an IQ of 71 — so the state said he could be put to death.

But the high court, in a 5-4 decision along ideological lines, said such a line is too rigid.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, who wrote the court's opinion, said the experts who design, give and interpret IQ tests say they reveal only a range — that a person's IQ may be five points above or below the score.

That means Hall could actually have an IQ of between 66 and 76. For that reason, the court held, he must be allowed to present evidence of his intellectual disability, including deficits in functioning over his lifetime.

"The death penalty is the gravest sentence our society may impose. Persons facing that most severe sanction must has a fair opportunity to show that the Constitution prohibits their execution," Kennedy wrote.

Hall was sentenced to death for abducting and murdering a 21-year-old pregnant woman, Karol Hurst, in 1978. He also shot and killed a sheriff's deputy.

His lawyers contend that he is functionally illiterate and has brain damage, psychosis, a speech impediment, a learning disability, and the short-term memory of a first-grader.

The Florida attorney general's office said it was reviewing the ruling and had no immediate comment.

Hall's lawyer, Eric Pinkard, said in a statement that the court "has recognized that 'intellectual disability is a condition, not a number' and that consequently Florida cannot ignore the standard error of measurement inherent in all IQ tests."

The Supreme Court decision means the Florida courts must take a new look at whether Hall has significantly below-average intelligence, taking into account other evidence such as school records.

John Blume, a Cornell law professor who worked on Hall's case, said the ruling could also affect inmates in four other states: Kentucky, Virginia, Alabama and North Carolina.

Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, which opposes capital punishment, said the decision was notable but would not affect many death-row inmates.

"People with mental retardation are 2.5 % of the population. It might be a little higher on death row. So we are not talking hundreds of inmates here," he said.

"But this is a further refinement of the court’s restrictions on the death penalty and it makes it clear they meant what they said in 2002: people with mental retardation under the normal definition in the profession should be excluded. It’s not each state deciding for itself."

The American Psychological Association also applauded the ruling.

"We are pleased that the majority of the court agreed that Florida's use of a fixed IQ score cutoff to determine a defendant's intellectual functioning is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of how to interpret IQ tests," said Nathalie Gilfoyle, the group's general counsel.