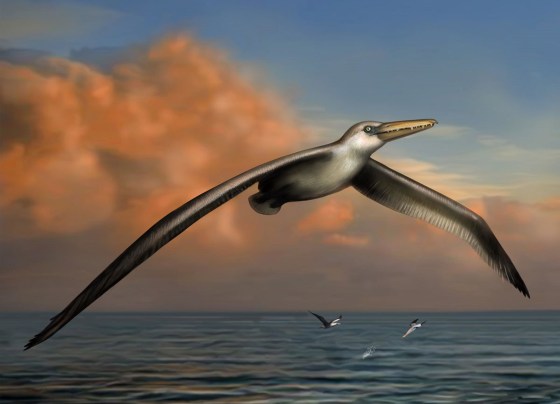

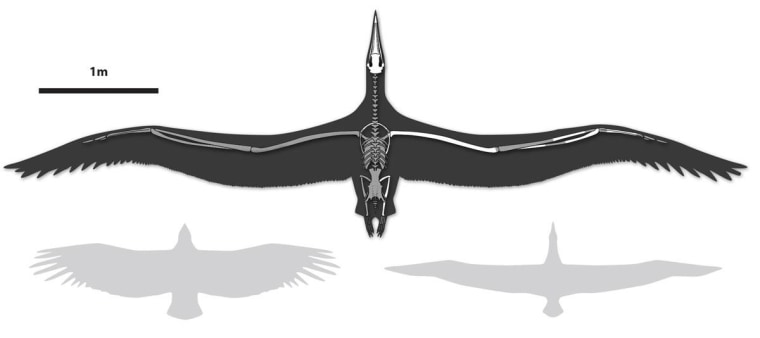

Behold the ultimate Big Bird — a seabird called Pelagornis sandersi, which probably needed a running start to take to the air because of its absurdly wide 20- to 24-foot wingspan.

The fossilized bones of the giant creature were found more than 30 years ago near Charleston, South Carolina, during excavations for a new airport terminal. But the skeleton hinted at a bird so big that researchers puzzled over how it flew.

Sign up for Science news delivered to your inbox

Dan Ksepka, a paleontologist who recently moved from the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in North Carolina to become curator of science at the Bruce Museum in Connecticut, fed the fossil's vital statistics into a computer simulation to determine how the bird could have done 25 million to 28 million years ago.

The simulation suggests that the spiky-jawed bird, classified as a pelagornithid, couldn't take off from a standstill. It probably had to run downhill into a headwind or take advantage of a gust of air to get itself aloft. But once it was airborne, it could glide for miles and miles over the ocean without flapping its wings.

P. sandersi could swoop down to snag eels or other prey from the sea, then soar back into a holding pattern. "That's important in the ocean, where food is patchy," Ksepka said in a news release.

Ksepka's findings are being published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The bird's wingspan was arguably wider than that of Argentavis magnificens, which has held the title of all-time largest flying bird (with a 23-foot wingspan). That far outdoes the 12-foot wingspan of the wandering albatross, the living bird with the widest wings. However, the fossil record points to heavier flightless birds (such as Aepyornis) as well as bigger winged creatures (such as Quetzalcoatlus).