NORTH LAS VEGAS, Nev. — The International Space Station's next module looks like a hot tub wrapped up in bulletproof fabric, sitting on the floor of a Las Vegas warehouse — but when the module goes into orbit later this year, NASA plans to unfold it into the outer-space equivalent of a rec room.

"This could be a very nice module potentially for the crews to go hang out in. ... It may become a very popular place," Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA's associate administrator for human exploration and operations, told journalists who gathered Thursday at Bigelow Aerospace's Las Vegas headquarters for the module's unveiling.

But that's just the start. If the experimental module works out the way NASA and Bigelow Aerospace hope it does, we could be seeing even bigger and better expandable spacecraft, including monster space blimps that have twice as much volume as the International Space Station.

"Expandable systems are the spacecraft of the future," said Robert Bigelow, the billionaire founder of Bigelow Aerospace.

Thursday's event marked the public debut of the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module, or BEAM, which Bigelow Aerospace built under the terms of a $17.8 million contract with NASA.

Within the next few months, the BEAM module is due to be trucked east to Florida for processing. It'll be launched as early as September from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, aboard a robotic SpaceX Dragon cargo capsule.

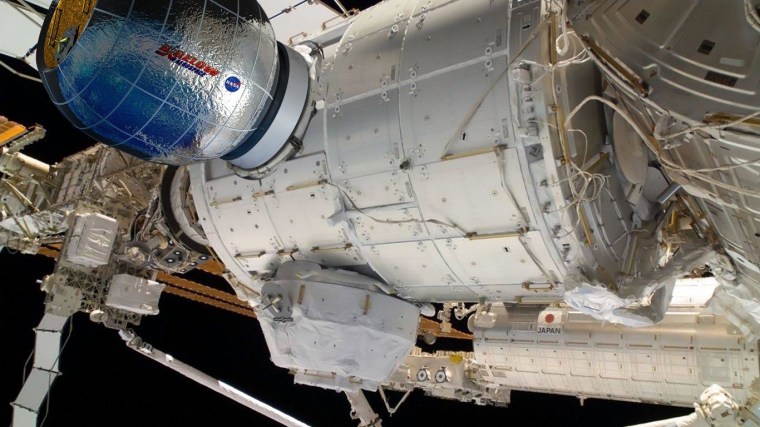

The Dragon will deliver BEAM to the space station in its folded-up, 5-by-7-foot (1.5-by-2-meter) configuration. Astronauts will use the station's robotic arm to attach the module to a docking port on the U.S.-built Tranquility node — and then they'll fill it up with air.

As it's inflated, the module is designed to expand like an air mattress — but with a many-layered, high-tech, bulletproof skin that Bigelow compares to the steel belts in a radial tire. When fully deployed, BEAM will provide as much volume as a 10-by-12-foot (3-by-4-meter) room.

NASA will conduct two years' worth of tests to determine how well the module holds pressure, how much protection it provides from space radiation and how resilient it is to impacts with tiny bits of orbital debris.

"It's the boring engineering stuff, but it's the stuff that we really need to do," Gerstenmaier said. "When we commit a spacecraft to a Mars kind of mission, you don't want to carry any uncertainty with you ... and a great place to do that is on [the space] station."

The expandable architecture provides a way to fit a big space module into a small cargo space. NASA engineers came up with the concept in the 1990s, to address the challenge of creating habitats big enough to sustain crews during their transit to Mars.

NASA had to drop the "TransHab" concept due to budget cuts — but Bigelow Aerospace picked it up, and turned the idea into two working prototypes that were launched into orbit on Russian rockets in 2006 and 2007. Those two Genesis modules are still in orbit today.

The success of Genesis gave NASA and Bigelow the confidence to go with the BEAM. This module will serve only as a test bed — and possibly a quiet hangout for the station's spacefliers. When the experiment is over, the module will be jettisoned to burn up in the atmosphere. That will free up the docking port for other spacecraft, Gerstenmaier said.

Next step: Stand-alone space stations

But that won't spell the end of the expandables: Bigelow Aerospace is already working on scaled-up versions that will offer 330 cubic meters of volume, compared with BEAM's 16 cubic meters. In comparison, the International Space Station has 916 cubic meters of pressurized volume.

The "B330s" would be marketed as stand-alone commercial space stations — for use by research organizations, by corporations or even by governments that don't have NASA-size budgets.

Bigelow said he has been holding off from building the first B330s until he was sure that private-sector spaceships would be available to ferry visitors back and forth. Thanks to NASA's support for the development of space taxis by the Boeing Co. and SpaceX, Bigelow is now confident that the spaceships will be ready sometime in the next two or three years.

"We are preparing, therefore, to produce two B330s to be able to be shipped out by the end of 2017, out of this facility, and then deployed in 2018 at some time," Bigelow said.

Bigelow said the first B330s would be launched into low Earth orbit, like the International Space Station, but he said it was too early to specify which launch vehicle or launch site would be used.

Hiroshi Kikuchi, senior managing director of Japan Manned Space Systems Corp., told NBC News that a wide variety of clients could use the Bigelow-made stations — including manufacturing companies such as Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, a major Japanese carmaker that he declined to identify, entertainment ventures and pharmaceutical companies.

"Many companies are waiting for the opportunity to use space station commercialization," Kikuchi told NBC News. "Bigelow Aerospace could make it happen."

Looking ahead to the moon and Mars

A full-size mockup for an even bigger expandable module, known as the Olympus, towered over the shop floor during Thursday's briefing. Bigelow said the Olympus would offer 2,250 cubic meters of pressurized volume — more than twice as much as the entire International Space Station.

He had no firm timetable for building the Olympus, but he said the monster module could serve as a warehouse in deep space, in lunar orbit, on the moon or on Mars. One of Bigelow's mission concepts calls for a fleet of lunar landers to be stored inside the structure.

The Olympus would weigh somewhere between 65 and 100 tons, which means it'd have to be launched on a super-heavy-lift rocket like NASA's Space Launch System. But the way Bigelow sees it, bigger is better when it comes to space exploration — and that's why he predicts expandable spacecraft will be the wave of the future.

"This particular field, with no pun intended, has enormous expansion possibilities," Bigelow said.