Updated 6 p.m. ET Sept. 23:

Now that experts are narrowing down their forecasts for the fall of the six-ton Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite, you can easily work out when to look for it streaking through the sky.

Here's the step-by-step process:

- Go to the Heavens-Above website.

- Select your "current observing site" ... the easiest way to do that is to click on the "from database" link, select your country ("U" for the United States), then enter a search string for a city name (say, "Dubuque," which is where I'll be on Friday). You can also use a map, or enter in your latitude and longitude manually.

- Submit your choice for observing site. That will bring you back to the home page, with your latitude/longitude listed.

- Click on the link for "All Passes of UARS."

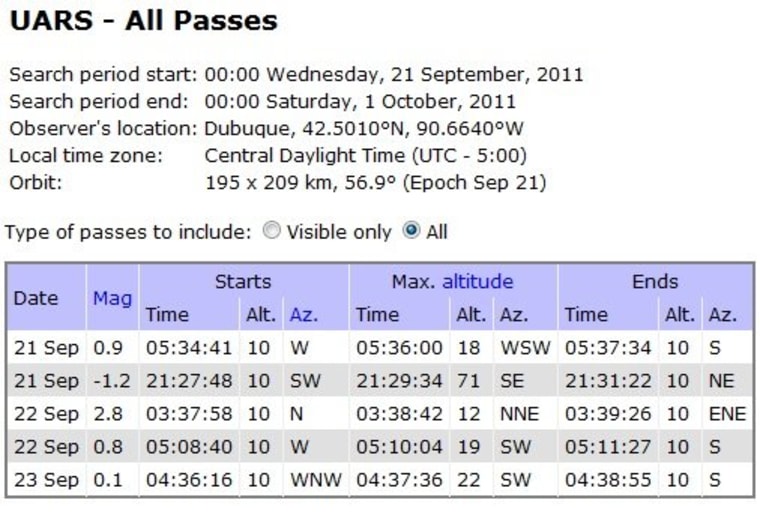

- Check out the chart that comes up, and make sure the correct time zone is listed. This chart lists all the times when UARS is within the line of sight from your location. Sometimes the satellite may passing by, but you can't see it because it's lost in the daylight, or it's not reflecting any sunglint. At other times, the satellite catches the glint of the sun just right to become visible in the sky. You can get a list of those sighting opportunities by clicking the "Visible Only" button instead of the "All" button.

This shows you when the UARS satellite is passing through between now and the end. But if you want to find out when there's any chance of seeing the UARS satellite fall, you have to focus on the passes that occur on Sept. 23 or early Sept. 24. For Dubuquers, there was an opportunity at 4:36 a.m. CT Sept. 24, as listed on the chart. The satellite wouldn't have been visible at that time — unless flaming pieces of debris were falling to the ground.

In that theoretical scenario, I would be watching for something streaking from west-northwest toward the south. But I wouldn't be looking very high in the sky. Heavens-Above is telling me that the maximum height above the horizon would be about 22 degrees. Ten degrees is roughly equivalent to the width of your fist held out at arm's length, so I'd look a little more than two fist-widths high.

The chart also tells me that debris from the satellite wouldn't have hit anywhere close to me, even if it was falling at the time, because the flyover is too far away. The "Alt" (altitude) listing is the key. "If your location has a pass with elevation above 80 degrees — that is, nearly overhead — then yes, you are in the potential debris scatter field," NBC News space analyst James Oberg said in an email explaining the process.

Fireworks on tap

What could observers see? Space.com's skywatching columnist, Joe Rao, said the blazing re-entry would look like a "short-lived but spectacular fireworks display." At an altitude of about 50 miles (80 kilometers), chunks of the burning satelllite would break off and create a series of meteoric streaks. Large pieces would flare into fireballs that could blaze as brightly as the full moon, if the re-entry occurred at night, Rao said.

It's far from certain that such a sight would be visible from the United States, based on NASA's estimates. The space agency said there was just a "low probability" that the satellite would be crossing North America when it made its final plunge, sometime late Friday or early Saturday.

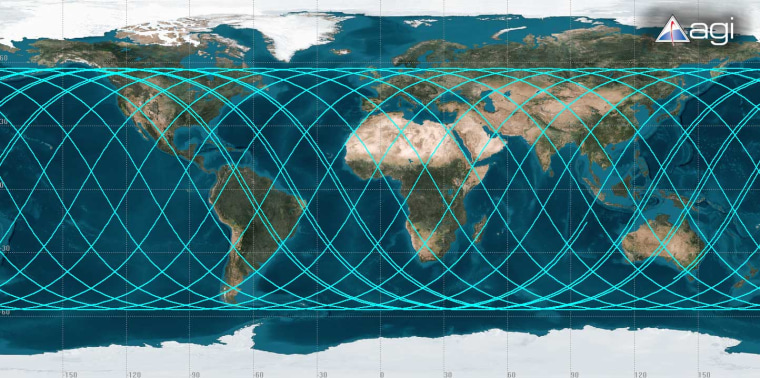

Other experts are offering different forecasts that have been all over the map ... literally.

The Aerospace Corp.'s prediction is being updated more frequently than NASA's. At one time, it pinpointed UARS' re-entry in the south Pacific, and then the crosshairs shifted to Chad in central Africa, and then back to the Pacific. All these predictions have a wide margin of error. NASA estimates that there'll be a 6,000-mile (10,000-kilometer) margin of error even two hours in advance of the fall.

Satellite-watchers are really hoping the debris from UARS falls somewhere near them, so they can witness a spectacular sky show (and maybe even catch it on video). But others are worried about the risk of injury or damage.

Reviewing the risk

The UARS satellite is the largest unmanned NASA spacecraft to make an uncontrolled descent since 1979, when the 10.5-ton Pegasus 2 satellite and NASA's 77-ton Skylab space station fell to Earth. (Other notable re-entries since then include the controlled deorbiting of Russia's 138-ton Mir space station in 2001, the controlled re-entry of the 17-ton Compton Gamma Ray Observatory in 2000 and the tragic loss of the shuttle Columbia and its crew in 2003.)

NASA says the chances that anyone in particular will be hurt by UARS debris are incredibly small: A couple of weeks ago, Nicholas Johnson, head of the space agency's Orbital Debris Program Office, estimated that there's a 1-in-3,200 chance of anyone being struck by fragments. When you divide that risk among the nearly 7 billion people in a potential debris zone that stretches in latitude from northern Canada to the southern tip of South America, the risk to any particular person comes to less than 1 in 20 trillion.

NASA doesn't intend to update those odds as more becomes known about UARS' path. Those are merely the generic risk statistics for the re-entry of any space debris as big as the six-ton satellite. Johnson said one object that big comes down through the atmosphere roughly once a year. "The odds don't change," he said.

Thousands of space objects streak through the atmosphere every year: Just last week, for example, a fireball sighted over the southwestern U.S. caused a huge stir. But Oberg said the case of UARS is special because we know in advance that a fiery fall is coming.

"Unlike most rocks from space that fall on our heads, this falling satellite is known in advance, and it is that lengthy anticipation, not the inherent hazard, that makes it so newsworthy," he said. "Bigger rocks fall to Earth much faster and every day — all naturally, but out of sight, out of mind."

More about the satellite saga:

- NASA: Satellite won't pass over America when it falls

- Watch the doomed satellite tumble in space

- What's the precedent for NASA's falling satellite?

Check NASA's UARS status page for updated information about the satellite's whereabouts, all the way to the end.

Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the log's Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter or adding me to your Google+ circle. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for other worlds.