A long, long time ago — between 378 million and 375 million years ago — about half of all species on the planet vanished. The trigger for this mass extinction, one of five known in Earth's history, was a lethal combination of sea level rise and invasive species, according to a new study.

"The basic processes that normally result in new species forming were blocked," study author Alycia Stigall, a paleobiologist at Ohio University, told me today.

In normal times, species are always going extinct, but as they die off, new species arise. That keeps the planet's number of species relatively constant. "When you take some species away but don't replace them, the overall result is a collapse in global biodiversity," she said.

The findings suggest that the planet's current ecosystems, which are experiencing loss of biodiversity, could meet a similar fate.

How species rise and fall

One path to the rise of new species starts when a population is split in half due to a geological event, such as the rise of a mountain chain that prevents the two halves of the population from interbreeding. Over time, the two groups develop into new species.

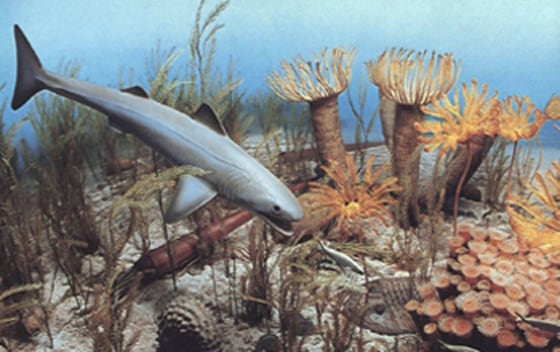

During the Late Devonian period that Stigall studied, most of Earth's creatures lived in shallow sea basins. As sea levels rose due to warming temperatures and shifting land masses, these basins were connected — that is, the barriers that kept them separate disappeared. New species stopped forming.

"The Devonian has normal extinction rates," Stigall noted. In other words, the number of species dying off wasn't abnormally high, as it was when a space rock slammed into Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula and killed off the dinosaurs about 65 million years ago. "So it is really the stopping of speciation that results in a major collapse.

"The other thing that happens when you raise sea level is some species move into that basin that didn't previously live there, and that's the invasive species," she added.

Some of these invasive species fail to carve out a niche for themselves and die off, but others — typically generalists that can eat almost anything and survive in a range of environments — outcompete the natives. "They basically take over and stop the ability of new species from forming," Stigall said.

Lessons for today

Many scientists say that we are in the throes of a sixth great mass-extinction event. The two main reasons are habitat loss — land converted to human use is less available to other critters — and the fact that we are moving species around the planet.

"What we can expect in the long term is that because we have this global movement of invasions, we can expect speciation rates to be very low, but we also know that because of habitat loss, the extinction rate is very high. So we are really looking at a very bad combined effect," Stigall said.

Knowing this, conservationists may be smartest to focus their efforts on generalist-type native species, she added.

"Things that are very narrowly adapted, specialist species, are unlikely to survive. They are unlikely to speciate in the future, and they are also unlikely to survive the habitat loss," she said. "So things like polar bears that are really cute — there's just not much we are going to be able to do for them."

Stigall's findings were published today in the journal PLoS ONE.

More stories about mass extinctions:

- Earth's Timeline: Where does the Devonian era fit in?

- Scientists: Haiti's wildlife faces mass extinction

- Is algae secret ingredient in mass extinctions?

- Mass extinctions may follow one-two punch

- Study sees mass extinction via warming

- Did Great Salt Lakes trigger mass extinction?

- Meteors not only culprit in mass extinction

- Mass extinction threat: Earth on verge of huge reset button?

John Roach is a contributing writer for msnbc.com. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by hitting the "like" button on the Cosmic Log Facebook page or following msnbc.com's science editor, Alan Boyle, on Twitter (@b0yle).