IBM's Watson supercomputer looks like the clear favorite to win this week's man-vs.-machine match on the "Jeopardy" TV game show in the wake of today's action. Right now, the score totals are $35,734 for Watson, vs. $10,400 and $4,800 for the game's two human champions. But even if by some miracle Watson doesn't take the million-dollar top prize, computer scientists say its performance will be judged a triumph for artificial intelligence.

"Watson is clearly playing at a championship level," inventor/futurist Ray Kurzweil, who predicts that A.I. will match human intelligence by the year 2029, told me today in an e-mail. "Note that it's only going to keep getting better. We cannot say that for unaided human intelligence."

Kurzweil said Watson merits the high praise he bestowed upon the machine after seeing its performance in last month's public practice round. In his essay on KurzweilAI.net, he said computers had "not shown an ability to deal with the subtlety and complexity of language" ... until Watson came onto the scene.

"Watson is a stunning example of the growing ability of computers to successfully invade this supposedly unique attribute of human intelligence," Kurzweil wrote. He said that level of language understanding, combined with a well-programmed aptitude for pattern recognition, would make Watson's descendants "far superior to a human."

Alien intelligence

Boris Katz, a computer scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who pioneered the development of natural-language question-answering systems, agrees that Watson is a wonder. "IBM did a fantastic job," he told me. But he said Watson's foibles also show that a computer's brand of intelligence is still alien to us.

When Watson is good, it's very, very good. But when it is bad, it's horrid. For example, one of the clues dropped during a practice round was: "This trusted friend is the first non-dairy powdered creamer." The correct answer was "Coffee-mate," but Watson gave a nonsensical non-non-dairy reply: "What is milk?"

Another example: On Monday, "Jeopardy" rival Ken Jennings gave a wrong answer for the decade when Oreo cookies were introduced (the '20s), and Watson followed up with what was basically the same answer. ("What is 1920s?") It was left to the third contestant, Brad Rutter, to come up with the right answer (the 1910s). Expert observers assume that Watson flubbed the answer because it didn't catch the fact that the '20s and the 1920s were just two different ways to refer to the same decade.

"When you look at the blunders, you realize that they did not build a machine that thinks like us," Katz said. "The success of Watson does not bring us closer to the understanding of human intelligence. When we observe it making these mistakes, that should remind all of us that this problem is still with us, and it's waiting to be solved."

Overconfident computer?

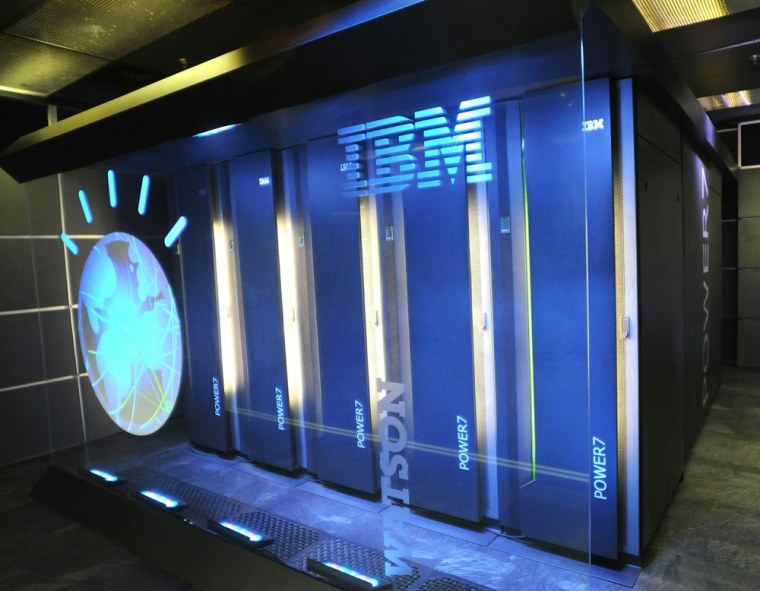

Watson draws upon 15 trillion bytes of information in its memory banks, the equivalent of 200 million pages of text, and ranks the potential answers for a given clue using 2,880 parallel processor cores in its 90 computer servers. If the highest-scoring answer exceeds its built-in "confidence threshold," it'll buzz in. If no answer scores high enough to reach the threshold, Watson will keep mum. At least theoretically.

"We're seeing already that there are times when Watson really doesn't have enough information to have a good answer, but has the 'confidence' to give an answer anyway," said Eric Nyberg, a computer scientist at Carnegie Mellon University who helped program the supercomputer.

Despite Watson's occasional missteps, Nyberg is proud of the computer's overall prowess, as well as the speed with which it's answering the "Jeopardy" questions. "I was pleasantly surprised that Watson was able to buzz in against Ken [Jennings], because in all of 'Jeopardy,' he's the guy with the fastest trigger finger," he told me.

Today, during an interview on MSNBC, Jennings acknowledged that Watson has "an edge on that buzzer that human reflexes have a hard time keeping up with." He also acknowledged that the pressure was on, big time, going into the final round. (Jennings actually knows who won, since the three shows were taped last month under tight security.)

"The computer can't get stage fright, it can't get discouraged or frustrated. It's like 'Terminator,' it's just going to keep coming," Jennings said. "And so the human race is going to have to play probably aggressively here — big bets where necessary, play recklessly to win."

On Wednesday, TV viewers will find out how this particular man-vs.-machine match ends. But the computer scientists emphasized that this is just the beginning for Watson and its successors. "The fact that it's this fast, and this accurate, and its abilities allow it to do this well at 'Jeopardy' means that question-answering technology is really ready for prime time," Nyberg said.

Watson was built to serve up quiz-show knowledge, but those question-answering capabilities would probably be most valuable in specialized fields such as medicine and law. Watson's kin could help us puny humans sift through millions of possibilities and come up with the five or six best medical diagnoses, or legal precedents, or chemical configurations, or ... well, you name it.

"We're not thinking about applications where there isn't a human in the loop," Nyberg said. "We're definitely talking about an intelligent information agent that's working with a human."

What do you think? Will Watson win this week's showdown? Will question-answering machines become our most reliable advisers? Or will this turn into a replay of "Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines"? Feel free to weigh in with your comments below.

Correction for 12:20 a.m. ET Feb. 16: Error! Error! I've fixed the humans' totals at the end of the first game, and have corrected The Associated Press' figures in the referenced story as well.

More human-vs.-machine matches:

- Chess computer beats world's best player

- Checkers computer becomes invincible

- Poker-playing robot beats human pros

- New Scientist: Computer beats human at Japanese chess

Join the Cosmic Log community by hitting the "like" button on the blog's Facebook page or following b0yle on Twitter.