I know you don't want to hear about automatic sequestration spending cuts; I don't either. We just wrapped up a big fiscal fight a few weeks ago, and the very mention of the word "sequester" makes eyes glaze over from coast to coast. I get that.

But it's time to start taking this seriously, anyway, because in about 30 days, some significant, deliberately painful cuts are due to kick in, and they pose an important risk to the fragile economic recovery.

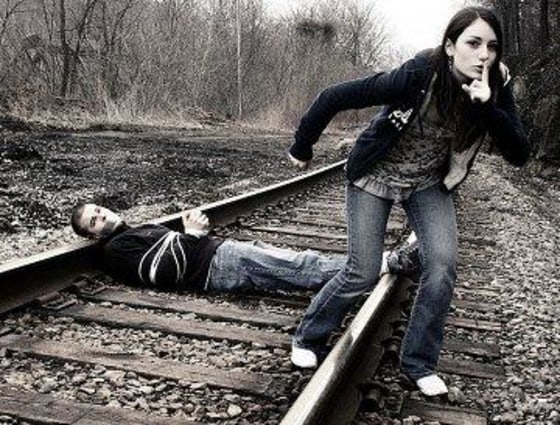

Remember, the sequester was designed to be horrible. Jon Stewart recently noted that these cuts are the equivalent of policymakers tying someone you care about to train tracks, on purpose, in order to create an incentive to find a solution before the train arrives. In this case, the solution would mean striking a bipartisan deal to replace $1.2 trillion in automatic spending cuts.

Both sides have said for over a year they fully intend to work something out, but with a month to go, they're actually moving further apart. Indeed, some Republicans now say they don't even intend to try to turn the sequester off.

On Sunday morning, Rep. Paul Ryan reiterated a message that House Republicans have been trying to push since the fiscal cliff deal happened: The GOP is unafraid to let the sequester take effect.

"I think the sequester is going to happen," Ryan said on NBC's "Meet the Press."

Ryan, who used to believe sequestration would "devastate" the economy, added, "[W]e can't lose those spending cuts." The same day, House Armed Services Committee Chairman Buck McKeon (R-Calif.) said of the sequester, "I'm pretty sure it is going to happen now. I guess the feeling is until everybody feels enough pain, we're not going to do the things that we really need to do. And that scares me."

Just so we're clear, these leading GOP officials are saying it's critically important to take money out of the economy, deliberately, no matter how much it hurts or how much damage it does. [Update: to see the effects of spending cuts on economic growth, see this morning's news.]

On the other hand, Republicans like Sens. John McCain and Lindsey Graham remain committed to turning the sequester off, fearing that the automatic cuts to defense spending, especially during a war, would seriously undermine national security.

This is already getting messy, and it's likely to deteriorate further.

As we discussed last week, there is a resolution here. Congress can replace the sequester with a balanced deal -- about $600 billion in cuts alongside $600 billion in revenue by way of tax reforms that enjoy bipartisan support.

The problem is, Republicans have ruled out the possibility of any compromise that includes revenue -- they don't want to reduce the debt; they want to shrink government. If there's a deal to replace these looming cuts, it can't be a 50%-50% split, the GOP says, it must be 100% cuts, 0% revenue.

For what it's worth, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) seems to have a plan.

"There are many low-hanging pieces of fruit out there that Republicans have said they agreed on previously," Reid added. "I'm not going to go into detail, but one of them, of course, is deal with oil companies."

That's a tip of the hand. As the sequestration deadline approaches at the end of next month, Republicans will be stuck with an absolutist line. Letting the sequester hit would be better than replacing it with even a penny of revenue; and their offer, from the last Congress, is to replace the entire sequester largely with deep cuts to social programs for the poor.

Democrats will have a counteroffer. Perhaps the parties can't agree on a complete sequester replacement. But they can pay it down for a few months with popular cuts and revenue raisers, including by eliminating tax subsidies for oil companies.

"[T]here's a lot of things we can do out there, and we're going to make an effort to make sure that ... sequestration involves revenue," Reid added.

Policymakers have a month to figure something out.