From working as a bouncer at a Buenos Aires nightclub to presiding over the Vatican, the path Pope Francis forged as the leader of the Roman Catholic Church was as unlikely as it was unprecedented.

Francis, who died Monday at age 88, was keen to flex his muscles as supreme pontiff. He angered some Catholic Church traditionalists by reaching out to gay and marginalized people, demanding justice for the poor and the dispossessed and railing against unbridled capitalism and climate change.

As the first pope from the Americas, Francis was in many ways the ultimate Vatican outsider who charted a new and more liberal course as the leader of the world's 1.4 billion Catholics.

“He embarked on a real reorganization of the church and a real reorientation of the church after four decades of conservative theologians’ leading the way,” said David Gibson, director of the Fordham Center on Religion and Culture.

Case in point: Francis announced a radical change in Vatican policy in December 2023 by formally allowing priests to bless same-sex couples. Still, he continued to oppose gay marriage, to the dismay of more liberal Catholics.

Francis also ratcheted up action against the sexual abuse of children by Catholic Church clergy by issuing the most extensive revision to its law in four decades, calling it “our shame.”

And he steadfastly championed the plight of migrants when many countries, including the United States, were closing their borders and right-wing politicians were demonizing them.

“We cannot remain indifferent in the face of such human dramas,” the pope said in a “60 Minutes” interview in May 2024. “The globalization of indifference is a very ugly disease. Very ugly.”

Francis pointedly criticized President Donald Trump’s attempt, during his first term in office, to prevent migrants fleeing violence in Central America from getting into the United States by building a wall on the border with Mexico.

“I realize that with this problem, a government has a hot potato in its hands, but it must be resolved differently, humanely, not with razor wire,” Francis insisted.

But in doing so, Francis alienated many Catholics and Republicans in the United States who supported Trump and his border wall.

To be sure, Francis was also criticized by the church's progressive wing. He refused to consider ordaining women. Victims of sexual abuse said his changes weren't strong enough. And he was accused last year of using a highly offensive term to describe gay men in a closed-door meeting, two weeks after the Vatican apologized for his use of the same slur.

Francis faced the stiffest resistance from archconservative American clerics during the pandemic when he urged people to get vaccinated against Covid. He also found himself being accused of heresy for, among other things, softening the ban on giving Communion to divorced and civilly remarried Catholics.

Still, in many ways, Francis was cut from the same conservative clerical cloth as his predecessors Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict. He was against abortion, in favor of clerical celibacy and opposed to ordaining women, although he was open to giving them a greater role in running the church.

It was Francis, after all, who gave final approval to make John Paul II, a religiously conservative Pole and another pontiff from “a faraway land,” a saint.

Despite Francis’ attempts to weed out sex abusers from the clerical ranks, many victims didn’t believe he went far enough to address the problem and punish offenders.

In 2018, Francisoutraged abuse victims by accusing them of slandering Chilean Bishop Juan Barros with claims that he turned a blind eye to priestly predators. Francis later apologized for demanding that the victims show “proof” that Barros did anything wrong.

In a remarkable letter addressed to the bishops of Chile, Pope Francis admitted making “serious mistakes in the assessment and perception of the situation.”

But Francis, who as a young manworked as a bouncer before he found his calling, didn’t hesitate to denounce his conservative critics, openly accusing them of “gagging” the church’s attempts to modernize.

“Coming from the other side of the world, he brought a different way of seeing the world, and throughout his papacy that was a constant,” said Kathleen Cummings, director of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism at the University of Notre Dame.

“To go from a church that was known for its rules and what it said no to, Pope Francis is a pope who has repeatedly said yes — yes to marginalized groups, yes to mercy — and that’s meant a lot to people.”

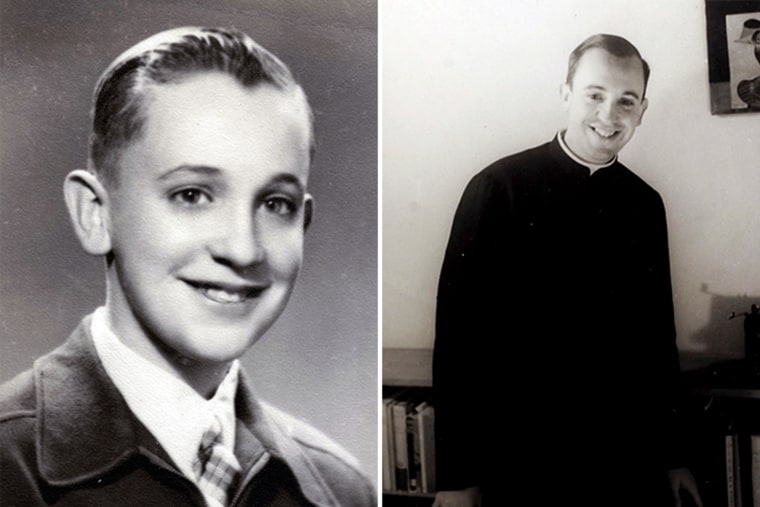

Born Jorge Mario Bergoglio on Dec. 17, 1936, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Francis was the first pope from South America, and not just South America, but the Americas overall.

The son of Italian immigrant parents, his father, Mario Jose Bergoglio, was an accountant for the country's railways, and his mother, Regina Maria Sivori, was a housewife. He studied chemistry before he entered the seminary, and he was 32 when he was ordained in 1969.

Four years later, Francis became head of the Jesuits in Argentina and was elevated to cardinal by John Paul II in 2001. Soon, Francis’ name was on the short list of possible successors to the Polish pope, who died in 2005.

But Francis was a runner-up that year in the conclave that elected German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger to become Pope Benedict XVI. His turn came eight years later, after Benedict’s abrupt resignation.

Francis took the reins of a church that was tarnished by financial scandals and still reeling the first papal resignation in 600 years.

He moved quickly to re-establish order. He often likened the church to “a field hospital after battle,” where the first things priests need to do for their congregants is stop the bleeding.

“It is useless to ask a seriously injured person if he has high cholesterol and about the level of his blood sugars,” Francis said. “You have to heal his wounds. Then we can talk about everything else. Heal the wounds, heal the wounds. ... And you have to start from the ground up.”

The first Jesuit to occupy the Chair of St. Peter, Francis took the name of St. Francis of Assisi, a 12th century figure who famously turned his back on family wealth in favor of a monastic life of service to the poor and the environment.

“Other popes have had the same message,” the Rev. Kevin O’Brien, then the vice president for mission and ministry at Georgetown University, was quoted as saying in a 2015 article about the pope’s leadership style. “But Francis has been very insistent in keeping this message at the forefront — servant leadership and caring for those most in need first.”

Francis cut a modest and almost deferential figure in his first hours as pope on March 13, 2013, when he greeted the crowd gathered below his balcony in St. Peter’s Square with a bow.

“You know that it was the duty of the conclave to give Rome a bishop,” he said. “It seems that my brother cardinals have gone to the ends of the Earth to get one ... but here we are.”

The next morning, Francis returned to the boarding house where he had been staying to collect his belongings and settle the bill.

Instead of the traditional papal apartments at the Apostolic Palace, Francis chose to live at the Casa Santa Marta, a simple residence in the Vatican used by official visitors.

While Francis had little use for the trappings of the papacy, he understood the need for the pomp of the office. Like John Paul II, Francis was a skilled communicator who knew how to work a crowd. And unlike the more reserved Benedict, Francis was eager to embrace people, and not just fellow Catholics.

When he was introduced to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp survivor Lidia Maksymowicz, he leaned over and kissed the number that the Nazis had tattooed on her arm.

While John Paul II used his papacy to take on communism and antisemitism, Francis spoke out against the “idolatry of money” and an unfair global economic system that forced millions to live in poverty. He stood up for the mostly Muslim migrants from poor and war-torn countries such as Libya and Syria who were seeking shelter in Europe.

In his first official trip outside Rome, he celebrated Mass on the tiny Mediterranean island of Lampedusa to commemorate migrants who drowned crossing the sea from North Africa.

“We have become used to other people’s suffering — it doesn’t concern us, it doesn’t interest us, it’s none of our business,” Francis said in his homily from an altar built from an old fishing boat to symbolize the migrants’ perilous crossing.

Determined to pastor to the global church, Francis traveled extensively, visiting South America, Asia, Africa, the Middle East and the United States.

In 2021, Francis made the first visit by a pope to Iraq, risking his own security (he later learned of foiled assassination attempts against him), and urged the country’s dwindling number of Christians to stay put and help rebuild the country after years of war.

More recently, Francis condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine, calling it a “negation of God’s dream.”

“Let the desperate cry of the suffering people be heard,” Francis declared. “Have respect for human life and stop the macabre destruction of cities and villages in the east of Ukraine.”

Francis met three times with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

But in a rare misstep on the international stage, Francis angered Ukrainians and their allies when, in a radio interview with a Swiss broadcaster last year, he suggested that Ukraine should have the “courage of the white flag” and negotiate to end the war with Russia.

“Our flag is a yellow and blue one,” Ukraine’s foreign minister at the time, Dmytro Kuleba, responded online. “This is the flag by which we live, die, and prevail. We shall never raise any other flags.”

Duncan Dormor, an Anglican priest who co-wrote “Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, and the Renewal of the Church,” said Francis believed in protecting people and used the Gospels as his guide.

“He’s interested in spirituality and how you really care for people,” Dormor said in an interview before Francis’ death. “That shapes who he is and how he is.”

“He takes the path of Jesus Christ and the Gospels deadly seriously, and he is seeking to follow in that pattern.”

In 2015, Francis became only the third pope to visit the White House and the first to address Congress, where he urged lawmakers to tackle climate change, a theme he returned to often over his tenure.

When President Joe Biden rejoined the Paris Agreement to limit global warming, the Vatican welcomed the move.

In 2020, Francis elevated 13 clergymen from around the world to the rank of cardinal. One of them was the archbishop of Washington, D.C., Wilton Gregory, the first African American appointed to the Catholic Church’s highest governing body.

Gregory’s appointment was significant for another reason — he was part of a select group of Catholic leaders who criticized Trump for staging a picture in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church near the White House during protests over the police killing of George Floyd.

Francis also helped broker a historic thaw between the United States and Cuba before he traveled to the communist country in 2015 and met with former leader Fidel Castro.

The apparent rapprochement between Francis and Castro also didn’t go over well with many Catholic conservatives in the United States.

But by that point, they had already soured on Francis, starting in 2013 when he spoke out against discrimination against gays and lesbians, unveiling a markedly more accepting attitude toward a long-ostracized community.

“If a person is gay and seeks God and has goodwill, who am I to judge him?” he told reporters in 2013.

In January 2021, Francis changed church law to formally allow women to serve as readers at liturgies and as altar servers, acknowledging in canon law what had already been taking place in many churches around the world and preventing more conservative leaders from blocking women from those roles.

Then, in May 2021, Francis launched an initiative to make Catholic institutions environmentally sustainable in seven years, saying a “predatory attitude” toward the planet must end.

In July of that year, Francis reimposed restrictions on the old-style Latin Masses. He said Latin-only Masses were being used to divide the church, even though his two predecessors, John Paul II and Benedict, had allowed them.

In addition, Francis faced open rebellion from high-ranking church leaders like Bishop Joseph E. Strickland of Tyler, Texas, one of his fiercest critics among U.S. Roman Catholic conservatives and an ardent Trump supporter.

When Strickland refused to step down following a Vatican investigation into the administration and finances of the Diocese of Tyler, Francis in November 2023 took the rare step of dismissing him from his post.

But Francis also, at times, disappointed more liberal-minded Catholics.

“He is always perceived as stirring up a discussion and not making it clear what he thinks,” said Lewis Ayres, a professor of Catholic and historical theology at Durham University in the United Kingdom.

He said Francis’ early comments about gays and lesbians weren’t followed up with any significant changes in church theology.

“If you think about him as if he were the CEO of a big corporation, you would probably say he’s not very effective,” Ayres said. “He’s highly charismatic, but he’s not effective.

“There’s a big difference between the way he appears in the media and in popular discussion and how he will be viewed by people more internally in the church over time,” he added. “The more you know about the business of the church, the more people are less certain he’s doing it properly.”

The first signs that Francis’ health was deteriorating appeared when he started using a wheelchair after having suffered increased mobility problems.

Soon, the Catholic media and other news organizations began speculating about whether he would step down, as Benedict had done before him.

Francis fueled those rumors further when he announced plans for a visit in August 2022 to the Italian city of L’Aquila for a feast initiated by Pope Celestine V. That pope also resigned while he was still in office, albeit more than 700 years before Benedict.

With an eye on preserving his legacy, Francis in December elevated 21 new cardinals, all but one of whom were under age 80 and thus eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope.

They included the 44-year-old head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in Melbourne, Australia, Mykola Bychok.

Meanwhile, Francis was hobbled by bouts of influenza and other related health issues. He underwent surgery in 2021 to address a painful condition called diverticulitis, and in 2023, he had another operation to repair a hernia.

In January 2024, Francis appeared in a sling after he injured his right forearm in a fall at his residence. The Vatican confirmed that no bones were broken, but the tumble came weeks after he bruised his face in another fall in December, Reuters reported.

In February, Francis was admitted to the hospital for bronchitis treatment and canceled all scheduled events for the next three days. It turned out to be pneumonia.

Cummings, of Notre Dame, said Francis may not have accomplished everything he hoped for, but he was a leader whose charisma and desire to connect with people will long be remembered.

“Has he managed to unite the church? No,” Cummings said. “But he’s managed to give many people who had little hope in their church renewed hope.”