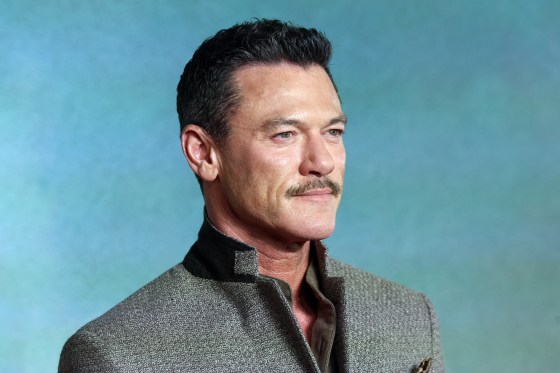

Luke Evans has carved out a niche for himself playing rugged, tough guys in “The Hobbit,” “Fast & Furious” and “Beauty and the Beast.” But in a new book, the Welsh actor showcases a more sensitive side, offering an intimate look at his journey of self-acceptance away from the constraints of his religious upbringing.

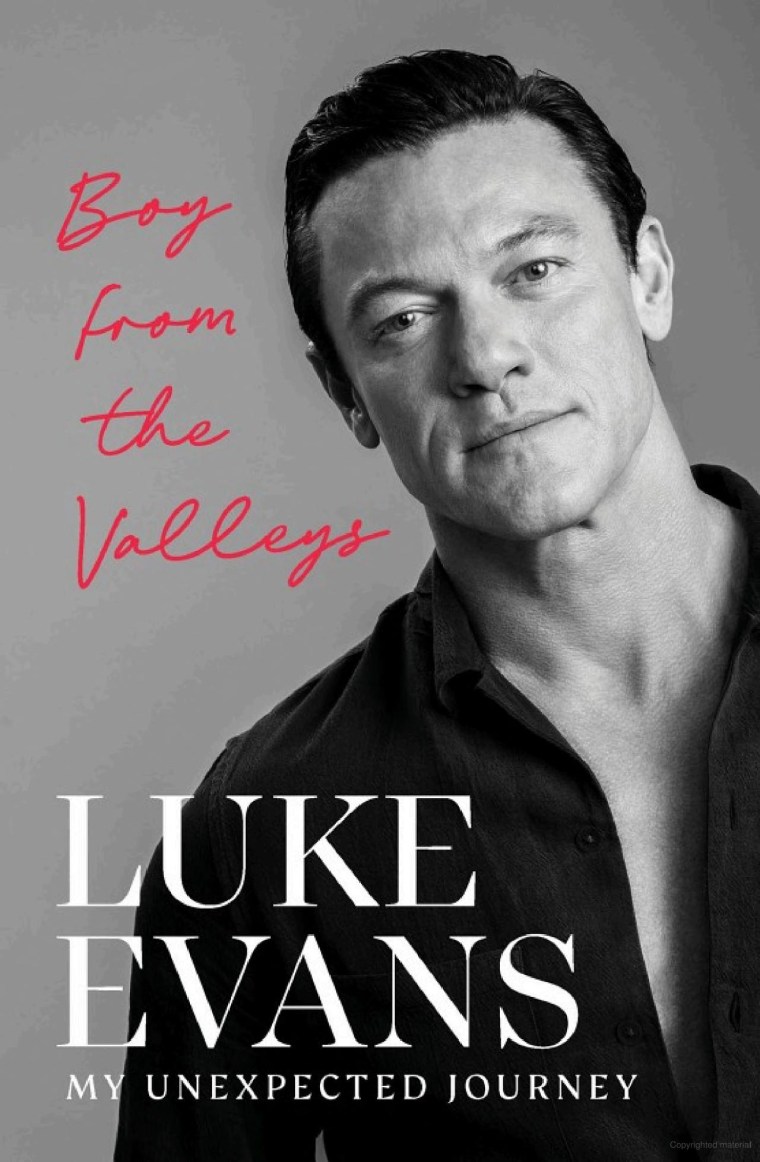

With equal parts heart and humor, Evans tells his own story for the first time in “Boy From the Valleys,” which arrived on North American bookshelves this week. The candid memoir charts Evans’ journey from growing up in South Wales as a closeted only child of devout Jehovah’s Witness parents to becoming, as a magazine once put it, “the first openly gay action hero” in Hollywood.

After having largely shied away from discussing his personal life in the public eye, Evans writes with unflinching honesty about the most formative experiences of his life — the internalized self-hatred of growing up in a faith that outlaws homosexuality, the highs and lows of his first sexual experiences and relationships, and the many “sliding doors” moments, which, taken together, put him on the path to doing plays and musicals on London’s West End and starring in multibillion-dollar film franchises.

“When I went into writing this book, I thought, ‘Don’t be ashamed of anything in your life. It’s part of your journey. It’s part of your tapestry,’” Evans, 45, told NBC News. “Some of it may be a little dark, some of it may not be as pretty as other parts, but it’s your story. I think you’ve got to own it and do the best you can with what you’re given.”

Evans became the youngest boy in his Welsh congregation to be baptized. But even with his limited view of the world, from an early age, he knew that he was destined for a bigger life outside of the village in which he was raised. By the time he turned 16, he recalled feeling the need to leave his hometown out of necessity, despite the personal fallout for his family.

“I’m very proud of that young kid. I don’t know how he managed to get through it all,” said Evans, who dedicated the memoir, in part, to his younger self. “Obviously, there was a lot of help and a lot of opportunities and ‘sliding doors’ moments that I absolutely took, which opened doors that possibly would never have opened to me. So I look back with pride at what I did. I wasn’t brought up with a family with money or a family who wanted me to do anything other than knock doors and be a Jehovah’s Witness.”

But Evans admitted the first decade he spent away from the church was rife with emotional turmoil and upheaval.

"There was no question that I had to start again, in a way," he said. "Unfortunately, the religion really dictates that when you leave, you don’t just leave, everybody leaves you as well, and you lose everybody."

In his memoir, Evans recalls the isolation he experienced in his late teens and early adulthood, which he combated with finding his own tribe of queer people in London.

“It’s just another instance of how brutal a religion that professes to care for people can be,” he writes. “Where’s the compassion, the acceptance that we’re all different? I find it astonishing that religious dogma can lead people to act so heartlessly.”

Despite his desire to venture out on his own, Evans admits that he was always most scared of losing his connection to his parents, who were forced to cut off all contact with him for years. (He came out to his mother at age 18 and then his father in his early 20s.)

“The thought of losing them because of something I couldn’t do anything about was a very scary, painful moment. Luckily, it didn’t go the bad way; it went the right way,” explained Evans, whose parents are still practicing Witnesses but have since found a way to reconcile their faith with their unconditional love for their son.

Reaching that place of reconciliation took “a lot of time and patience and acceptance and understanding, which didn’t come overnight,” he continued, adding that he no longer feels the “urge or need to attach” himself to a religion anymore. “But I’ve tried to prove to my parents that my journey is about living my life to the fullest, wanting to fulfill my dreams. Part of my life is my sexuality, but it certainly isn’t the forefront of every decision I make. It’s just part of who I am.”

In his book, Evans writes candidly about the vitriol he received from the queer community during his early days in Hollywood, when he was accused of seemingly hiding his sexuality despite having spoken about it years earlier while doing musical theater in London.

“The hardest part was they’re making an assumption and drawing a picture of me, and they knew nothing about me, apart from how this newspaper was written or my films. They knew absolutely nothing about my childhood or my life. But I realized those people weren’t affecting me; I was allowing it to affect me,” Evans recalled of that period of his life. “It was hurtful for a moment, and then I became resilient. I thought, ‘My God, I’ve been through way worse than this.’ I will just brush it off and carry on working, carry on doing what I love, and keeping my friends close.”

With his extensive body of work over the last two decades, Evans has redefined what is possible for an out gay actor in Hollywood, becoming a heartthrob to male and female audiences alike.

“I would like to think that I’m a perfect example that anything is possible. I’m a very happy, content, gay actor in movies where I can play a straight person, and I’m absolutely fine with that,” he said. “We can represent ourselves in normal life, but also as an actor, you can represent anybody. That’s the wonder of being an actor.”

Evans said he hopes his personal journey and professional success serves as a positive, yet "quiet message."

“I understand that when you are the first, or people perceive you as the first, then you have a role to play. But I was never going to shout it from the rooftops. It is not who I am, never has been,” he said. “It’s an observation people make that, ‘He’s doing his thing, and he is happy and he is accepted, and that people accept him in anything he does,’ which I’m very grateful for. That does mean things are changing in a positive way.”

Since the memoir's publication late last year in Europe, Evans said he has received dozens of “messages from people around the world who’ve been through what I went through, or resonated with a part of my story and felt inspired to find their authentic self because of me finding mine.”

“Some of them have brought a tear to my eye. Some were humorous, some were very painful, some were traumatizing to read,” he said. “But they were so happy to know that somebody else had gone through it and had spoken so publicly, so honestly, about something so raw and painful, and they knew it was going to help other people.”