While Nathan Witthoft was earning his PhD at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he met a woman with color-grapheme synesthesia, a neurological condition where people see letters and numbers in color. Most color-grapheme synesthetes perceive the alphabet in their own color scheme, with each letter possessing a different hue. When tested on her synesthesia, Witthoft noticed that it had reoccurring colors, as if her alphabet followed a set, repeated pattern. She mentioned that as a child she had a set of colored alphabet magnets and her letters matched the colors of the letters in the set.

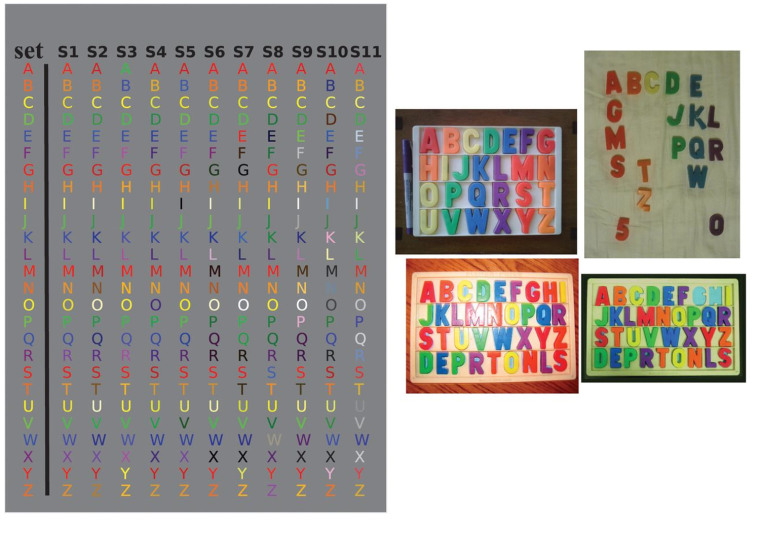

Witthoft wrote a paper about her and soon others contacted him, noting that their synesthesia mimicked the colors of the magnets. He recruited 11 synesthetes to visit the lab and take some tests. First, he asked the subjects to participate in a battery of tests to determine whether they were, in fact, synesthetes (the tests come from synesthete.org; anyone can register and take them online). Then, they participated in a timed color-matching test, where they selected the shade that corresponded with their letter.

He found that all 11 subjects had a similarly colored alphabet that paralleled the childhood magnet set. All but one of the participants recalled having this toy during their childhoods. This is the first time researchers found that color-grapheme synesthetes shared common patterns.

“I had been surprised by how easy it was to find people [whose synesthesia mirrors the magnetic alphabet toy],” says Witthoft, a post-doctoral researcher at Stanford University in the psychology department.

Additionally, these color patterns stay constant. The woman from MIT participated in this study as well and her alphabet remained similar to what it was seven years ago. All the subjects completed the matching test twice with about 50 days in between—both times the letters possessed the same shades. These findings are consistent with researchers’ understanding of synesthesia as being specific, automatic, and constant.

However, this research doesn’t mean that synesthesia can be learned.

“I know plenty of people who have this magnet set [who aren’t synesthetes]. The fact that we found so many people, or found it at all, is surprising. It’s a thing that was made possible [because of] a mass-produced toy,” says Witthoft.

While synesthesia is likely genetic, these findings show the influence of the environment on learning. Without the neurological underpinnings of synesthesia, people won’t simply learn to see letters in color. Yet, people who have the genetic disposition for it pick up the color scheme because of environment.

“For most of the people who are synesthetes … they are not aware of it [until they’re teenagers]. They think everyone has it and think everyone sees the same thing they do. They are having this kind of experience from stimuli in the world; it’s just there in the world and they are not aware that it comes from them. And there is nothing about their everyday world that informs them it is [unusual],” he says.

The paper appears in the journal Psychological Science.