Neither the Great Recession, nor the sluggish recovery, nor a widening wealth gap has shaken many Americans’ belief that they are solidly middle class, a new NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll shows.

Despite a rapidly shifting economy that’s largely hollowed out middle-class jobs and deepened inequality in the last generation, few think of themselves as poor (or even as well-to-do), the poll reveals.

“Given the significant amount of economic dislocation we’ve had as a country, and the changing nature of the economy, it’s remarkable how stable attitudes have been,” said Fred Yang, a partner with the Garin Hart Yang Research Group, which produced the NBC/WSJ poll in partnership with Public Opinion Strategies.

Experts such as Yang say the results show that the income group you identify with is less about facts — such as how much is in your paycheck or how valuable your home is — and more about the symbolism attached to the class into which Americans think they fit. That’s even true for Americans from different income and racial groups.

“Despite shifts in income, and employment, changes in population from immigration, class identities are stable.”

The poll shows that the percentage of Americans who identify as middle class has budged very little since the 1990s: in 1998, 46 percent of Americans said they were in the middle class. Today, 41 percent of Americans rank themselves in that cohort.

“In terms of how we describe ourselves, between 17 years ago and today, there’s very little shift,” said Bill McInturff of Public Opinion Strategies. “Despite shifts in income, and employment, changes in population from immigration, class identities are stable.”

For two generations, the ranks of the middle class, when measured as a measure of income, have shrunk, and in the last decade that's largely because the proportion of Americans earning low incomes has grown. In the last 15 years, the percent of Americans earning below 150 percent the poverty line has grown from 31 percent to 34 percent. At the same time, wealth inequality has grown to levels not seen for 80 years.

Yet like middle class identification, the percentage of Americans identifying as working class or upper middle class has also remained steady since 1998.

And even as inequality grows, with more wealth flowing to the top of the economic ladder, very few see themselves as poor or as affluent. While more Americans did say they were poor in 2013 than in 1998—12 percent versus 6 percent—that number has now returned to 9 percent. And the percentage of Americans who call themselves well-to-do has never risen above 3 percent.

What's 'middle class'? It's unclear

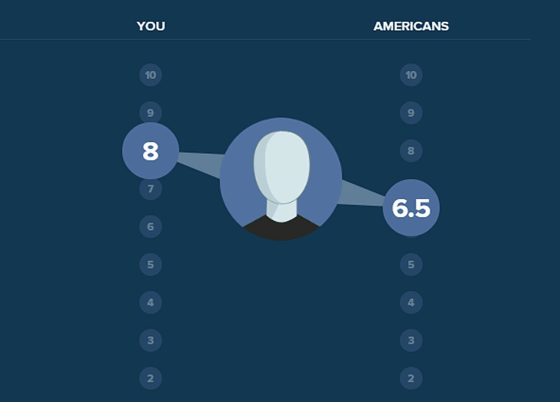

NBCNews’ “Who Do You Think You Are?” Quiz, based on analysis of data from the General Social Survey data suggests similarly that class identities are based not simply on how much money we earn, but on factors including how content we are, how we feel we’re doing relative to those around us and how much our parents earned when we were teenagers.

“Class in the contemporary United States is not simply a statement about income, or education,” says Joshua Clinton, a political science professor at Vanderbilt University and NBC’s data consultant on the quiz. “It’s based on a complicated set of factors and characteristics.”

While American class identification has not significantly changed, what those identities mean varies significantly between racial and geographic groups.

While all groups of Americans identify as middle class at the same rate — about 40 percent of whites, blacks and Latinos say they're middle class — blacks and Latinos in that category earn less than white Americans who also identify as middle class.

What Americans imagine amounts to a middle class household income depends also on how much money they already earn. Of Americans making less than $30,000 a year, 71 percent say that households earning less than $50,000 are part of the middle class. Only 17 percent of those earning more than $75,000 a year would consider those making less than $50,000 to be in the middle class.

Similarly, those who did not finish high school have a lower threshold for what counts as middle class than more educated Americans.

Unequal optimism

Overall, between 2013 and 2015, Americans on the lower rungs of the American class scale became slightly more optimistic about their future economic prospects. “People who are poor and working class are feeling better than they did a couple years ago—they can see a way out for themselves,” says McInturff.

But the optimism was not equally shared. In 2015, just one third of whites who said they are poor or working class think they’ll move up the class scale in the next five years. About half of African Americans and Latinos — 49 percent and 53 percent, respectively — feel such optimism, even though African Americans and Latinos are more likely than whites to identify as working class or poor.

“The worry is that [my kids] are not going to be able to get to the point that we were able to get to. If they want to buy a home, to make a similar standard of living, I’m not sure they can, not without working two jobs.” - Steve Newberg, 60, Connecticut.

“The belief in the American Dream, in upward mobility looks to be stronger among low income black and Hispanics than whites,” says Yang. “There’s more optimism in upward mobility among people of color.”

Yet blacks and Latino identify as middle class are also more likely than whites to fear falling from that position. Thirty-two percent of middle class blacks, 25 percent of middle class Latinos and 14 percent of middle class whites say they think it’s likely they’ll lose their standing.

“Class is really very much about perception, about where you stand and your relationship to others,” Clinton says.

This story is part of a series: "Class In America: Who Do You Think You Are?" Read the series here.