In an as-told-to essay for College Game Plan, Matthew Rooda, co-founder of SwineTech, explains what he learned navigating the business development process. SwineTech works to save piglets with the help of wearable devices.

The CEO: Matthew Rooda, 23, co-founder (with Abraham Espinoza) of SwineTech

School: University of Iowa Class of 2017

From: New Sharon, Iowa

Based in: Iowa City and Cedar Rapids

Number of employees: 7

Time I spent working: 10-12 hours

Time I spent studying: 3-4 hours

Time I spent sleeping: 5-6 hours

How we got started

SwineTech started about 18 months ago, through the university’s student accelerator. Then we went through the Iowa Student Accelerator out of Cedar Rapids.

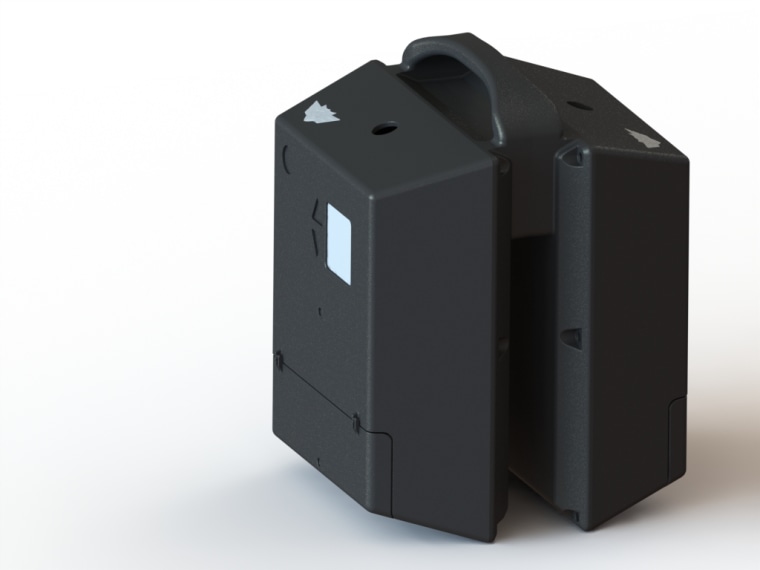

During my freshman and sophomore years I was a manager of a sow (hog) farm in Waterloo, Iowa. The moms were crushing their babies. We knew we could condition the pigs to avoid this through a series of vibrations, so we developed a wearable device that would send vibrations to the mom if she was crushing her piglet. The device detects the sound of a distressed piglet.

If the mom received a vibration, she would stand up. The more often she gets up, the more often she eats and drinks, which helps with overall health. The sows live longer, they’re less stressed, they’re happier. It was a good side effect.

Sows give birth into crates at some farrowing farms. Those actually reduce the problem by about half. On a farm where a pig can walk around while it’s giving birth, it’ll crush twice as many babies. But we see SwineTech’s wearable as a way to help increase space for sows, and also productivity for farmers. Each wearable will have health tracking to help farmers know more about their sows, how healthy are they, if they’re eating appropriately. They can give them as much care and attention as possible.

This is a problem everybody’s facing all around the world, whether you’re a small farmer or a big farmer: 116 million piglets are crushed every year. That’s 22.5 billion pounds of pork that never makes it to market. It’s a big waste.

Juggling business and school

We developed a routine. We scheduled all our classes after 5 p.m. Business came first, and school always came second. But we still managed to get decent grades. The hardest part was convincing a professor that you weren’t going to make class because investors would say 'I want to meet you in two days in Manhattan.' Teachers would ask, 'How come you couldn’t give us any notice?' And we'd say, we didn’t know!

You try to squeeze in as much as possible, and then work out, and eat. You miss a lot of meals.

How I define success

If I can reduce this problem by another 50 percent, help cut the amount of piglets that die from this in half, I would say we’re successful, but I really want to help the pork industry get to where the dairy industry is now.

Dairy cattle just live life. You don’t have to interfere with what they’re doing every day. A farmer can just look at a computer and know what’s happening. How can we automate it so that pigs can live healthily and so that farmers can afford to raise pigs? Helping them manage things a little better is our goal.

What's next

There are ways of using the audio processing technology that we have patented to identify respiratory illnesses in livestock, so that’s one area where we might expand to. I know my co-founder, Abraham Espinoza, would love to someday start a school in Mexico that focuses on entrepreneurship. I have a lot of aspirations to help in developing countries in Africa.

My advice for other young entrepreneurs

Some people say you can’t be afraid to fail; I personally think you can’t be afraid to ask for help. There’s almost certainly someone who’s gone through what you’re going through, and can help you avoid obstacles.