With the Federal Reserve ordering severe constraints on bank overdraft fees and Congress considering even tougher rules, U.S. banks face a serious dilemma: How to replace the potential loss of billions in fee revenue?

Consumer groups that have been fighting the costly "courtesy overdraft protection" fear that banks have hit on a replacement that might be even worse – a crop of products with names like "Direct Deposit Advance" that are being pushed by lenders such as U.S. Bank, Wells Fargo and Fifth Third Bank. The advances have a stated annual percentage rate of 120 percent but -- if calculated as a traditional loan product -- could have an APR of well over 1,000 percent.

"Banks are trying to figure out a way to keep getting high fees from consumers once the Fed and Congress tighten up overdrafts, and I think this will be the next big abuse," said Lauren Saunders, managing attorney at the National Consumer Law Center.

Here's how the lending products work. Consumers who have an existing relationship with a bank and a history of automatic direct deposits are pre-authorized to borrow up to $500 at the click of a mouse. U.S. Bank's "Checking Account Advance" product also allows account holders to borrow directly through its ATMs.

Cost is generally $10 for every $100 borrowed. There is very little risk for banks, because the money is repaid from the consumer's next direct deposit. But account holders pay interest rates far higher than those of the riskiest loans.

Assuming the payment arrives one month later, the interest rate is 10 percent for a month, or 120 percent for a year. But most consumers would repay the loan much sooner, whenever their next paycheck arrives at the bank. If payment arrives within a week, the loan's APR would be around 520 percent, notes Jean Ann Fox of the Consumer Federation of America. If payment arrives in two days, the interest rate would be 1,850 percent.

Because banks define the product as a line of credit rather than a loan, they are allowed to calculate interest based on a 30-day billing cycle.

"It should be shocking enough that banks say they charge 120 percent interest," Saunders said. "But these are loans you will likely take out only a few days ... so the real rate is likely, much, much higher."

At an online forum sponsored by the American Banker trade newspaper this summer, Terry Zink, executive vice president of Fifth Third Bank, bragged about the potential of his firm's new lending product, now called "Early Access." He said customers see the advance lending product as a valuable service, rather than overdraft fees, which are seen as punitive.

"If we pre-sell an overdraft in the form of a direct deposit advance, customers then are opting to buy, versus being punished for doing something," American Banker quoted him as saying. He said consumers have "overwhelmingly accepted" the products, adding that 80 percent of those who use it are repeat customers.

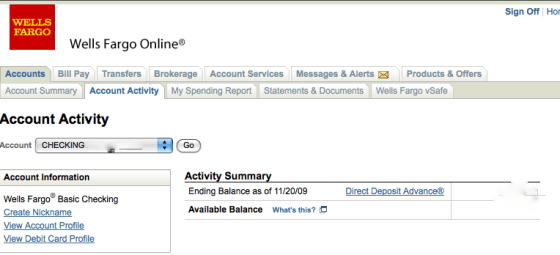

Today, Wells Fargo customers who log in to their online banking Web sites and click on "account activity" have the opportunity to obtain a direct deposit advance by clicking on a prominent link next to their available balance.

The service is not new, said Julia Tunis Bernard, a spokeswoman for Wells Fargo. She said the bank introduced direct deposit advance in California in 1994, and has offered the service in the 24 states where it has branches for about 10 years.

"We do several things to make sure our customers understand this is an expensive form of credit," she said. "...We try to educate customers to consider lower cost forms of credit."

On Wells Fargo's Web site, there is a warning and a link to other Wells Fargo lending products.

"It not intended to solve someone's credit issues. It's meant to get people through emergency situations ... to help customers who are in a financial pinch"

She defended the bank's stated 120 percent APR, saying Wells performed the calculation "according to federal regulations for an open-ended line of credit."

But Saunders warned that consumers who borrow using direct deposit advance services might not realize how quickly they can dig themselves into a hole.

"Remember, that next direct deposit to the account could be a Social Security check or an unemployment check, money that's protected from debt collection, targeted at core necessities like food. But in this case, the banks get first crack at it," she said. "These could be worse than payday loans."

If for some reason, consumers do not make a new deposit to cover the cost of the borrowed amount, banks will pull the funds directly out of consumers' checking accounts on the 35th day. If the money is not there, consumers could be hit with a double-whammy of high-interest borrowing and overdraft fees, Fox warns.

"If a borrower is unable to repay a $100 checking account advance at U.S. Bank within 35 days, the bank collects $10 for the initial advance, the bank's $37.50 maximum overdraft fee, and $8 every day after four days that the account remains overdrawn and the loan unpaid," she wrote in a recent report. "If the loan is not repaid until 7 days after the due date, the borrower would have paid $71.50 for a 42-day $100 loan. That comes to roughly 621 percent APR if calculated as a closed-end payday loan would be."

Become a Red Tape Chronicles Facebook fan and follow RedTapeChron on Twitter.