Abstract

With the disruption of nonessential research due to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers faced unexpected changes in their work and personal life. We assessed what challenges researchers encountered during lockdown and whether gender, career level, discipline, and job-permanency influenced their experiences (negative and positive), thereby collecting empirical material which could provide valuable information for future mentoring/supporting practices. Data were collected between July-August 2020 via an online-survey, and answers from 210 respondents (78% female, 21% male, 1% non-disclosed gender) working in Animal Behaviour and Welfare (ABW, 57%), other biological sciences (37%) or social sciences (6%) were analysed. Respondents were post-graduate students (35%), research associates (35%), and professors (22%) or classified as ‘other’ (8%), and overall fixed-term (55%) and permanent (45%) jobholders. We expected that early career researchers, non-permanent jobholders, and female respondents would report more challenges/less positive experiences during lockdown. Due to the widespread impact of the pandemic, we predicted no effect of academic disciplines. We found great inter-individual difference in the experiences reported by the respondents, with some reporting adaptation to a new routine within a week (31% of the respondents) and/or greater efficiency working from home (19%) while others felt less efficient working from home and/or experienced a greater imbalance towards work (30%) and/or increased personal responsibilities (24%). The most commonly reported challenges were the lack of informal contact with colleagues (63%), a loss of focus due to worry or stress (53%) and/or unsuitable working environments (47%). Postgraduate students, research associates, non-permanent jobholders and ABW researchers reported more work-related challenges (p = from 0.03 to <0.0001) and were more likely to worry about the future (p = from 0.0002 to <0.0001) than other career levels, permanent jobholders, and researchers from other disciplines respectively. We found no gender effect (p = from 0.006 [NS due to Benjamini-Liu correction for multiple comparisons, 24 metrics tested] to 1.000), except that female respondents reported more personal changes affecting their ability to work than male respondents (p = 0.037). On a positive note, most respondents (83%) perceived positive changes during lockdown and 60% reported one or more coping strategies during lockdown, with exercising/outdoor activities and interacting with family/friends most commonly reported. Based on our findings, we provide recommendations for overcoming the reported Covid-19-related challenges which could further deliver valuable guidance for supporting/mentoring schemes and activities fostering a more resilient research community.

Keywords: COVID-19, Work management, Challenge, Positive experience, Coping strategies, Mentoring

1. Introduction

In early 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic situation unprecedentedly required researchers to stop all nonessential activities to mitigate the fast spread of the virus. Research disruption took place quickly, constraining investigators to stop months’ long experiments, and/or to postpone projects, going home with limited data to support progresses (e.g.Denfeld et al., 2020; Sevelius et al., 2020). The impact of this cessation has been even more significant for early career researchers (‘ECRs’ hereafter), who are particularly pressured to progress in their career development (e.g.Cranford, 2020; Denfeld et al., 2020; Levine and Rathmell, 2020; Sohn, 2016; Woolston, 2020b). Furthermore, training, networking and job opportunities have quickly decreased during the pandemic (Cranford, 2020), with such an impact being expected to persist long-term as academic institutions are experiencing extraordinary financial challenges (Witze, 2020; Woolston, 2020a). Furthermore, this uncertainty about the future arose in a situation presenting an experience of confinement which many of us have never experienced before, including transitioning from a world of freedom to limited agency, regulations of the way we socially interact, potentially unsuitable working environments, and/or shift in greater responsibilities related to personal life. All of these challenges could thus make adjusting to working remotely particularly challenging (Stephens et al., 2020; Kesner and Horáček, 2020), and even more so for ECRs (Kong and Chan, 2020; Inouye et al., 2020).

As it became clear that the situation would prolong, access to support systems appeared therefore critical to help academics navigate these challenges and maintain good well-being. For ECRs in particular, mentoring and support may also help them to not prematurely depart to pursue opportunities in industry or other areas (Cameron et al., 2020; Denfeld et al., 2020; Levine and Rathmell, 2020). Support and mentoring happen at various levels, from interacting with line managers, local colleagues and mentors, to being provided outside institutions, e.g. via scientific networks and societies mentoring schemes. Such programs appear particularly timely to develop/reinforce during the Covid-19 pandemic, as quantity and/or quality of local supports might vary, due to colleagues and mentors themselves being under such strong pressure to adjust to working remotely that their usual mentoring practices are significantly impacted (Fernandez and Shaw, 2020; Cameron et al., 2020). Furthermore, providing support and mentoring both inside and outside institutions allows each individual to be exposed to a wider range of perspectives on the challenges faced. This might help with recognising others’ experience and realign expectations in support practices, promote sustained mentoring relationships during the crisis, and ultimately boost resilience (Cameron et al., 2020; Stephens et al., 2020; Denfeld et al., 2020; Earvolino-Ramirez, 2007).

This study aimed to provide such empirical material that can help with developing evidence-based, tailored supporting/mentoring practice to ultimately boost our academic community members’ resilience during Covid-19-related challenges associated with both temporary and permanent changes in research practices. To do so, we have documented the experiences of researchers at different career levels (from postgraduate students to professors) in managing work during the COVID-19 lockdown, in order to identify a range of both negative and positive individual experiences, as well as coping strategies associated with the situation. The survey was open to any academic discipline and broadly targeted the following aspects: difficulties/easiness in finding a work routine during the lockdown, challenges experienced (broadly related to social challenges, inabilities to work efficiently, worrying about the future, and/or increased personal responsibilities), and positive experiences and coping strategies (e.g. finding abetter work-life balance). We explored the effects of four factors that might be associated with variations in the respondents’ experiences, i.e. career level, permanency of job (proxy for risk of unemployment), gender and academic discipline. We predicted that early career researchers (Kong and Chan, 2020; Inouye et al., 2020), non-permanent jobholders (Paul and Moser, 2009) and female respondents (e.g.Stadnyk and Black, 2020; Malisch et al., 2020; Kamerlin and Wittung-Stafshede, 2020; Oleschuk, 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2020) would report more challenges / less positive experiences during the pandemic. Due to the worldwide impact of the Covid-19 situation and in view of published literature at the time we designed the survey, we did not expect experiences to differ across academic disciplines.

2. Methods

This study was approved in July 2020 by the Science and Engineering Human Ethics Committee of the University of Plymouth, Devon, UK (# 2020−2277-1232).

2.1. Survey design and data collection procedure

We designed a web-based survey using Jisc online surveys (onlinesurveys.ac.uk). The survey addressed the personal experiences of respondents during lockdown in three categories: 1) changes in work routine and management, 2) personal challenges affecting abilities to work, and 3) coping strategies and positive changes. The full survey is available in the supplementary material. Answers were collected via single or multiple-answer questions. In addition, free response options (i.e. writing in own wording) were available, allowing the respondent to provide more detailed answers.

Information about respondents’ gender, academic discipline, research position (from which we inferred career level), permanency of job and location of research activity was collected for descriptive purposes and to identify whether these factors were attributed to specific responses. However, all answers were anonymised before submission and respondents were able to withdraw their response within 14 days of submitting the survey. Respondents were required to be working on at least one research project at postgraduate level or higher.

We recruited participants globally through social media (e.g. Twitter, Facebook), research networks, scientific societies and institutions’ newsletters and mailing lists, and word of mouth. We specifically targeted researchers working in Animal Behaviour and Welfare or related fields (e.g. veterinary research) but welcomed participants from other academic disciplines, since we did not predict other research areas to be less effected by the pandemic. Hence, we considered the experiences of researchers of all disciplines to be equally relevant. However, given that we (the authors) work in the field of Animal Behaviour and Welfare, one may predict a slightly higher proportion of respondents to be from the same field as the authors’. Indeed, information was spread more widely within our own research community (e.g.via the Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour (ASAB), the International Society for Applied Ethology (ISAE), and the Animal Welfare Research Network (AWRN)), and respondents from this field might have identified more to, and were thus perhaps keener to participate in, a survey conducted by researchers from their own research area. The survey was launched on July 6th 2020, and remained available until August 10th 2020.

2.2. Respondents

We received 213 responses in total but three participants were excluded as they did not fulfil the requirements (one undergraduate student, one respondent on maternity leave and currently not working, and one person holding a non-research related position). Out of the remaining 210 respondents, 78% were female, 21% were male and 1% preferred not to disclose their gender. Most of the respondents were working in European countries (78%), followed by North America (15%), Oceania (2%), Africa (2%), South America (2%) and Asia (1%). Almost all respondents (92%) were located in the country of their current occupation during lockdown, but 8% were in a country different to their normal work location. A third of respondents (35%) were post-graduate students (PhD or MSc), another third (35%) were research associates, 22% were professors and 8% were classified as ‘other’ because their position did not fit the aforementioned categories (e.g. research technician, research lead).

The dataset was almost equally constituted of fixed-terms (55%) and permanent (45%) jobholders. Fifty-seven percent of the respondents worked within animal behaviour and welfare and directly related disciplines such as veterinary sciences (‘ABW’ hereafter), 37% worked in other biological science and medicine fields and 6% worked in social sciences.

2.3. Statistical analysis

2.3.1. Analyses of answers from single or multiple-answer questions

The proportion of respondents selecting the proposed options, and where relevant (i.e. for multiple-answer questions), and the number of options selected from the question, were calculated to summarise the respondents’ answers. Respondents were categorised according to their research disciplines (ABW or Others that included other disciplines in Biology, Medicine, and Social science), career level (postgraduate student, research associate, professor, or other), permanency of job (fixed-term or permanent) and gender (female or male respondent, discarding the two respondents who answered ‘Prefer not to say’ when analysing gender effects). Since almost all respondents (92%) were located in the country of their current occupation during lockdown, and most (78%) were based in Europe, we did not proceed in analysing location of research activity further.

We performed the statistical analyses in R (version 3.6.3; R Core team 2013), using the packages “gmodels” (general differences investigated with Fisher exact test) and “RVAideMemoire” (pair-wise differences investigated with Fisher exact test). The responses to each question (and pair-wise comparisons where relevant) were individually analysed using Fisher exact tests. Multiple-answer questions were transformed into binary variables (yes/no for each possible response) before being analysed using Fisher exact tests. The proportions of respondents reported in the text were calculated out of the 210 respondents unless stated otherwise (e.g. in section 3.3.1. Coping strategies reported by respondents). The number of answers given per respondent (where relevant) was also analysed using Generalised Linear Mixed Models and a Poisson distribution (no repeated or random effects were specified in the models). Tukey-Kramer correction was applied to pair-wise comparisons in these models. The numbers of options selected from multiple-answer questions reported in the text are Least Square Means (LSM) ± standard error (SE). LSM, standard error and statistical information (t-value and P-value) for comparisons not reaching statistically significant differences are presented in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Type I error-correction for multiple comparisons was performed with the Benjamini-Liu procedure (False Discovery Rate, Benjamini and Liu, 1999) resulting in adjustment of the significance level to p ≤ 0.0012.

2.3.2. Analysis of free style answers

Answers submitted in free style when respondents chose to specify or comment on multiple-choice questions, were compared by two of us (SK and CF) against the broad categories into which the proposed options could be categorised (e.g. social challenges, inabilities to work efficiently, worrying about the future, and/or increased personal responsibilities for section 2 challenges experienced). Should the free text contain information not represented by the broad categories targeted through the proposed options, the specific comments were selected and described in the results (but not quantitatively analysed due to low occurrence).

Our respondents were also asked to list any coping strategies that they had utilised during lockdown in an attempt to tackle negative feelings and low mood. In order to visualise these coping strategies, we produced a Wordcloud using WordArt (https://wordart.com/). The more frequently mentioned strategies are represented as larger, more prominent words within the cloud. The response of ‘No’ was also included in the WordCloud, to show that it was a deliberate response to indicate no coping strategy has worked for these individuals so far, or that they did not have identifiable coping strategies. Respondents could list as many strategies as they wanted. Because the answers were provided in freestyle, common words and connective words, as well as variations in spelling due to typos or language specificities (e.g. American and British English) often obscured the relevant words in the WordCloud. As a result, each answer was simplified into categories agreed by two of us (EF and CF). For example, the following answer: ‘Increased time investment into outdoor activities i.e. cycling, walks. Baking/cooking as a distraction’, was simplified into: ‘Outdoor activities, Exercising, Baking, Cooking’. This improved the software’s accuracy when ranking the frequency of words within responses. The top 40 most popular categorised responses were included in the WordCloud and a basic ‘cloud’ stencil, provided by the software, was used to achieve the shape.

3. Results

3.1. Work routine and management under lockdown

The answers to the questions of work-related changes experienced by respondents during lockdown varied across individuals. Some people reported no change in managing work, or even improvement compared to their ‘normal’ (i.e. pre-lockdown) working conditions. Indeed, 4% of respondents reported no change in their work routine and 31% needed only a week or less to (re-)establish it. Thirteen percent did not feel slow and/or distracted while working, 12% felt even more focused, and 20% and 19% respectively did not feel their efficiency while working had changed, or felt more efficient at work during lockdown. However, difficulties in managing work under lockdown were also reported. Indeed, establishing a work routine could take several weeks (two weeks: 14% of respondents, longer than two weeks: 9%), 33% reported their work routine was only intermittently established, and 8% were still trying to find it. A vast proportion of respondents felt somehow (33%) or clearly (27%) less efficient while working during lockdown, and slow and/or distracted, either at the beginning (23%), as lockdown carried on (14%) or during most of the lockdown (35%). We also found great individual variations in responses addressing changes in perceived work-life balance. Some people reported a greater imbalance towards work (30% of the 210 respondents), and/or towards more personal responsibilities (24%), and/or towards personal activities (21%), and/or an improved work-life balance (27%), and/or experienced no changes in work-life balance (7%)2 .

None of the factors we explored (i.e. career level, permanency of job, discipline and gender) explained these inter-individual variations (Table 1 ), with the exception of permanent staff reporting feeling more distracted than temporary staff specifically while conducting experimental work (p = 0.001; Supplementary Material Fig. S1).

Table 1.

P-values obtained from analysis with Fisher exact tests to identify the influence of individual factors (top row) on replies to each question. Benjamini-Liu correction was applied to reduce the risk of false positives and the adjusted p-value was 0.0012, thus only values equal or lower than that threshold (emphasised in bold, grey filled cells) are considered significant. ‘ABW’: Animal Welfare and Behaviour or related fields (e.g. veterinary research).

|

|

|

|

3.2. Challenges experienced during the lockdown

3.2.1. Reported challenges

The challenges experienced during the lockdown also varied across respondents. For questions allowing people to select multiple answer options, the numbers of challenges associated with work management reported by a single person varied between 0–7 aspects (Q14), 0–6 worries about the future regarding their career (Q15), and 0–5 personal changes that may have affected their ability to work (Q17). The most commonly experienced challenges among the proposed options in the multiple choice questions were a lack of informal contact with colleagues (reported by 63% of the 210 respondents), a loss of focus due to worry or stress (reported by 53% of respondents) and unsuitable working environments (47% of respondents). Interestingly, none of the broader categories into which these challenges could be categorised; i.e.social challenges, inabilities to work efficiently, worrying about the future, and increased personal responsibilities; appeared dominant in the respondents’ replies. In other words, people ‘as a whole’ do not seem to primarily worry about one of these categories more so than others (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Challenges experienced during lockdown (multiple-choice questions #14 to 17). Items with different layout fit into a broader category of: A) social challenges (italic font, light grey background), B) inabilities to work efficiently (normal font, white background), C) worrying about the future (white font, dark grey background), D) increased personal responsibilities (normal font, mediumgrey background).

|

From the free style comments, 11 people (5% of respondents) further reported difficulties in separating between work and home due to the lack of spatial differentiation between the two. Further, shifts in daily routine due to additional responsibilities, such as childcare or home schooling, were mentioned by 12 people (6% of respondents) to seriously impact their work efficiency and self-care including sleep.

3.2.2. Influence of career level, job permanency, discipline and gender on inter-individual variations in reported challenges

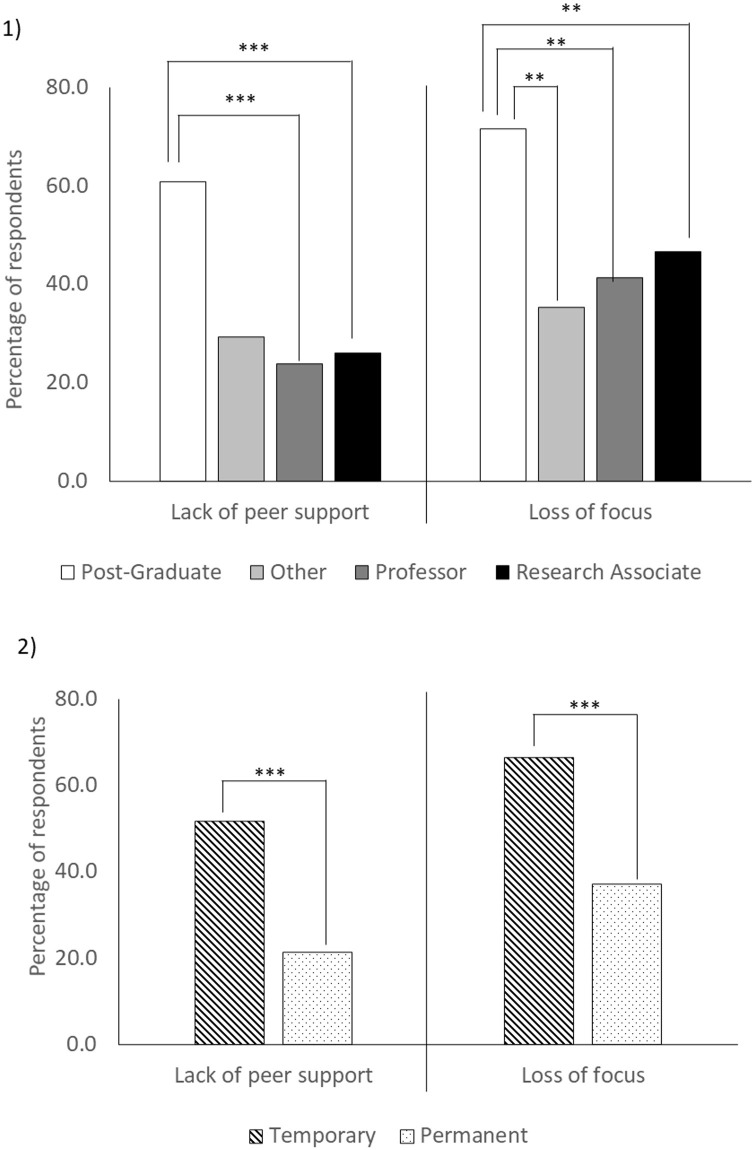

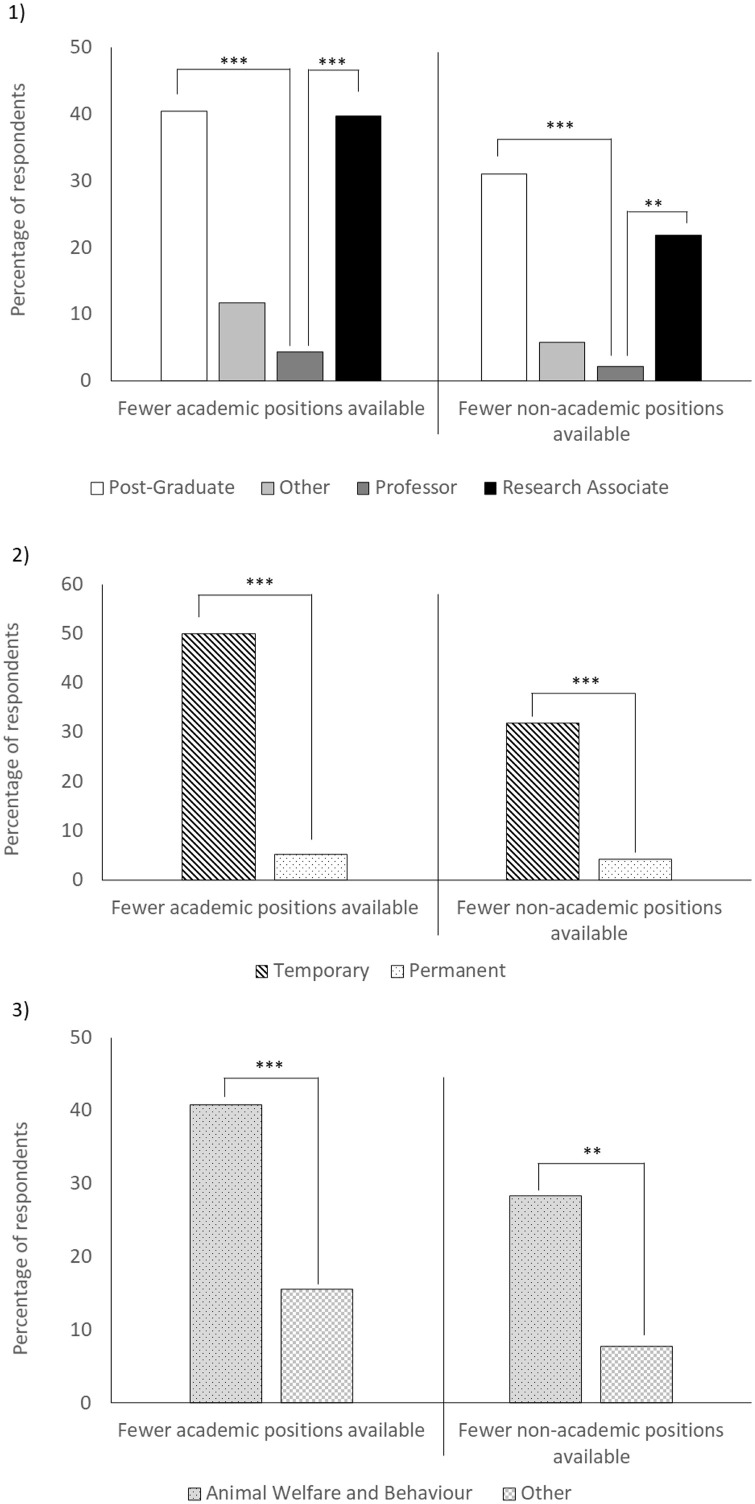

Career level and permanency of jobexplained inter-individual variations in the same questions about work-related challenges (Q14) and career worries (Q15). Career level and permanency of job were not independent from each other (Fisher test, p < 0.0001), asall postgraduate students were non-permanent job holders, all professors but one were permanent job holders, and research associates were divided between the two categories (34 non-permanent and 39 permanent job holders). This overlap between the two factors might explain why they contribute to inter-individual variations in the same subset of questions. Thus, a lack of peer support and a loss of focus due to worry or stress were more commonly reported by postgraduate students compared to other career levels (lack of support: p < 0.0001; loss of focus: p = 0.0009; Fisher exact tests, Fig. 1 .1), and by non-permanent jobholders compared to permanent staff (p < 0.0001 for both, Fisher exact tests) (Fig. 1.2). Research associates reported more worries per person about the future regarding their career than people holding the ‘Other’ position (1.63 ± 0.17 vs 0.63 ± 0.33; t201 = -2.775, p = 0.03; career level effect: F3,44 = 8.259, p < 0.0001); as did non-permanent jobholders compared to permanent staff (1.87 ± 0.21 vs 0.61 ± 0.18; F1,33.5 = 18.873, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, more postgraduates and research associates reported worries about the future availability of both academic (p < 0.0001, Fisher exact test) and non-academic (p < 0.0002, Fisher exact test) positions compared to other career levels (Fig. 2 .1), as did non-permanent jobholders compared to permanent staff (p < 0.0001 for both, Fisher exact test, Fig. 2.2).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of respondent reporting lack of peer support (left hand side) and loss of focus due to worries and stress (right hand side) in Q14 for (1) the different career levels (n postgraduate student = 74, n other = 17, n professor = 46, n research associate = 73) and (2) permanency (or not) of job (n temporary = 106, n permanent = 94). ** represent significant differences between the bars at p < 0.01 and *** represent significant differences between the bars at p < 0.001.

Fig. 2.

Effect of (1) carreer level (n postgraduate student = 74, n other = 17, n professor = 46, n research associate = 73), (2) permanancy of job (n temporary = 106, n permanent = 94) and (3) discipline (n animal welfare and behaviour = 120, n other biologists, medical researchers and social scientists = 90) on reporting worries about reduced availability of academic (left hand side) and non-academic positions (right hand side). ** represent significant differences between the bars at p < 0.01 and *** represent significant differences between the bars at p < 0.001.

Worrying about the future also appeared to be influenced by the discipline. Indeed, ABW respondents reported more worries per person about the future regarding their career compared to respondents working in other research disciplines (1.59 ± 0.156 worries per person for ABW respondents vs 0.90 ± 0.167 for other biologists, medical researchers and social scientists; F1,46.6 = 26.24, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, more ABW scientists reported worries about the future availability of both academic (p < 0.0001, Fisher exact test) and non-academic (p = 0.0002, Fisher exact test) positions, compared to scientists working in other research disciplines (Fig. 2.3).

Lastly,gender did not explain most of the observed inter-individual differences (Table 1), except that female respondents reported more personal changes that may have affected their ability to work than male respondents (on average respectively 0.94 ± 0.10 and 0.56 ± 0.16; F3,4.67 = 4.407, p = 0.037). Details of the modal scores of worries reported by each group are presented in Table S3.

3.3. Coping strategies and positive aspects

3.3.1. Coping strategies reported by respondents

Overall, 125 individuals (60% of respondents) provided coping strategies, from 1 to up to 8 coping strategies per person, with the majority providing 1 or 2 coping strategies (Supplementary Material Fig. S2). A total of 59 different coping strategies were mentioned, of which the top 40 most popular are presented in the word cloud (Fig. 3 ). The most common responses were ‘Exercising’ (50 responses), ‘Outdoor Activities’ (23 responses) and ‘Talking to Friends and Family’ (20 responses), suggesting that being outside and communicating with other people was a priority for many. ‘Embracing’ (14 responses), which referred to embracing the lockdown and the unprecedented circumstances, and also ‘Positive Thinking’ (9 responses) were also reported, suggesting that it was not only active endeavours that helped individuals cope, but also a purposeful attitude. Additional responses related to ‘Pet Care’ and ‘Nature’ were popular (total of 17 instances) and several popular hobbies such as ‘Cooking’, ‘Baking’, ‘Drawing’ and ‘Macrame’ were noted as successful coping mechanisms. Furthermore, health and wellbeing appeared to be a main priority for many, with ‘Rewarding Self’, ‘Self-Care’ and ‘Routine’ being popular responses (a total of 14 instances), as well as recognised relaxation techniques such as ‘Breathing Exercises’, ‘Yoga’ and ‘Meditation’ frequently mentioned (a total of 20 instances).

Fig. 3.

This WordCloud shows the 40 most common coping strategies among the 125 respondents who reported coping strategies. The more frequently mentioned strategies are represented as larger, more prominent words within the cloud, and relate to exercise and outdoor activities, as well as social interaction with friends and family and pet care. ‘Exercising’: includes walking, cycling, fitness classes, running, gymnastic, hiking, tai chi, hula hooping and unspecified (i.e. people reporting ‘exercising’ or ‘sport’ with no further details on the activities); excludes: dog walking (part of the ‘pet care’ category), yoga (kept separately since yoga practices can vary greatly in terms of physical effort and details allowing to classify the reported practices were not provided). Outdoor activities: includes gardening, spending time in the garden, and replies explicitly mentioning getting out of living spaces; excludes sunbathing (kept separately since sunbathing can happen inside using a window). ‘Healthy lifestyle’: includes paying attention to diet, and/or avoiding alcohol, taking break away from computer/screens.

3.3.2. Positive aspects experienced during the lockdown

The majority of respondents (83%) also reported perceived positive changes in their daily routine during lockdown (versus 8% of respondents not experiencing, and 9% not aware of experiencing such positive changes). The most commonly reported positive effects of the lockdown among the proposed options were: spending more time talking/engaging with family and friends than normal (reported by 45% of the 210 respondents), an improved work-life balance (34% of respondents), having time to catch-up on work that was stalled because other tasks previously took priority (31% of respondents) and starting/learning a new skill, hobby, or activity to improve professional and/or personal skills (30% of respondents). Some people (27%) also reported an improved physical health, and/or having more time to engage in activities they were already participating in before lockdown (25%) and an improved mental health (10%). Respondents who named positive changes in the free style answers (N = 25) mainly listed: time-saving due to not having to commute (5% of the 210 respondents), as well as being able to spend more time at home with family or partners (2%), more flexibility for work and free time activities (3%) and more time to sleep (3%). ABW respondents tended to report more positive effects emerging from lockdown per person than those working in other fields of research (2.13 ± 0.19 vs 1.66 ± 0.20, F1,9.2 = 9.173, P = 0.056). Research associates reported more positive effects per person than professors (2.3 ± 0.20 vs 1.3 ± 0.30, t201 = -2.973, P = 0.017; career level effect: F3,15.9 = 2.594, P = 0.09). Similarly, permanent staff tended to report more positive changes compared to temporary staff (2.19 ± 0.21 vs 1.6 ± 0.24, F1,7.1 = 2.867, P = 0.09).

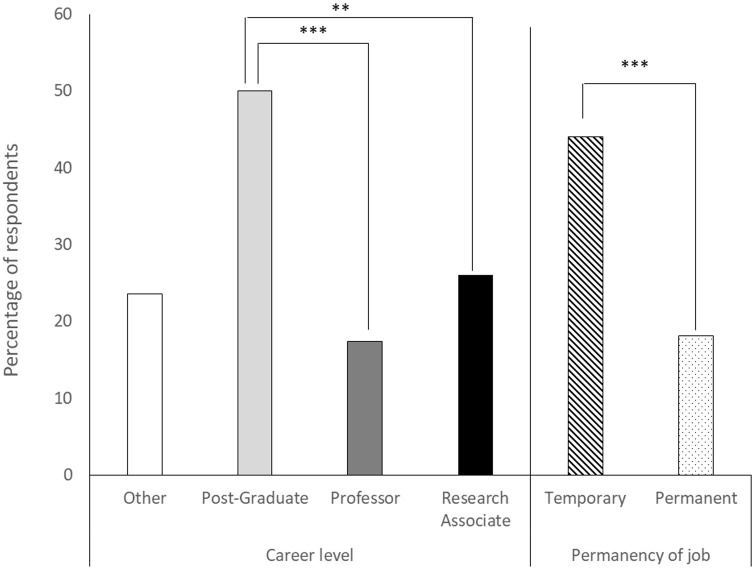

A large proportion of people were also willing to consciously make more time for activities they engaged in before lockdown (ticked by 56% of respondents) or continue with the activities they have taken up during lockdown (32%) once going back to ‘normal’ (pre-lockdown) conditions, while only 20% of respondents anticipated no change in their life after lockdown. More postgraduate students (compared to professors: p < 0.0004 and to research associates: p < 0.0038, Fisher exact tests) and more non-permanent jobholders (compared to permanent staff, p < 0.0001, Fisher exact tests) reported willingness to continue with the activities they have taken up during lockdown (Fig. 4 ). Six respondents stated in the free comments that they would like to continue working from home although not necessarily full-time.

Fig. 4.

Effect of career level (n postgraduate student = 74, n other = 17, n professor = 46, n research associate = 73) and permanency of job (n temporary = 106, n permanent = 94) on reported willingness to continue engaging in the activities people started during lockdown. * represent significant differences between the bars at p < 0.05, ** represent significant differences between the bars at p < 0.01 and *** represent significant differences between the bars at p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

We investigated what challenges, positive aspects, and coping strategies researchers encountered during lockdown, and whether experiences differed according to gender, career level, discipline, and job permanency. Respondents varied greatly in their replies indicating that individual’s experiences during lockdown cannot be generalised. Experiencing a lack of informal contact with colleagues, a loss of focus due to worry or stress, and unsuitable working environments were nevertheless commonly reported (at least half of the 210 respondents). As predicted, ECRs and non-permanent jobholders (the two factors being not independent from each other) reported a higher number of challenges experienced, including a lack of peer support and worries about the future. Unexpectedly, ABW researchers also reported a higher number of challenges and worries about the future compared to researchers from biological sciences, medicine and social sciences. Also, contrary to our predictions, gender largely did not explain inter-individual variations in the reported experiences. Based on this empirical material, we discuss below suggestions for future mentoring/supporting practices that could strengthen resilience within our research community.

4.1. Favour informal interactions with peers

The most commonly reported challenge was a lack of informal interactions with colleagues, which might have contributed to some respondents feeling less efficient, since positive relationships with colleagues benefit work engagement and productivity (Chiaburu and Harrison, 2008). The intersection of work and personal relationships appeared to be even more important to postgraduate students and non-permanent jobholders, who reported a lack in peer support as challenging more frequently than other career levels and permanent jobholders. Daily interactions with peers or mentors provide invaluable opportunities to PhD students that might influence student development and shape career aspirations (Wang and DeLaquil, 2020). Moreover, postgraduates might particularly benefit from informal research exchanges and seeking immediate advice which, now in COVID–affected times, requires an intentional, multistage formal process (Wang and DeLaquil, 2020).

As social species, interpersonal contacts regulate individual’s emotions and well-being (Zaki and Williams, 2013), and loneliness is associated with various consequences for physical (e.g. higher risk of cardiovascular disease, compromised immunity; shortened life span; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; Cacioppo et al., 2011) and mental health (e.g. increased risk of depression, Mushtaq, 2014). It is therefore not surprising that, in times of significant social restrictions, technologies providing social exchange received a spike in demand (e.g. Facebook +27%) during lockdown (Koeze and Popper, 2020) and social connectedness appeared to become especially important for coping. For instance, Austrian citizens with greater social connectedness during lockdown reported lower levels of perceived stress in general and COVID-19-related worries (Nitschke et al., 2020).

As the situation continues, increasing informal interactions with peers thus appears crucial, and opportunities to do so might happen at various levels, from interacting with local colleagues through to interacting outside institutions such as within scientific networks and societies. Small interventions such as internal research meetings or virtual coffee/lunch gatherings could provide opportunities to chat with the peers in an informal setting. Interestingly, while the latter has been well-attended by postgraduates from the authors’ school, the interest in proposed more formal, work-related interactions such as student-led research talks happened to be low at the time of lockdown (E. Churchill, pers. comm.). Although anecdotally, this highlights the need for informal contact during difficult times. People used a variety of non-work-related activities as coping strategies during lockdown (e.g. connecting with nature and animals, creative activities, learning new skills), and these activities may offer opportunities for increasing informal contacts between colleagues. This could be achieved via the creation of hobbies-focused social media groups, for example; and conducting virtual exhibitions merged within national/international societies events, such as the ‘Zoomorphism vs Anthropomorphism’ exhibition that took place during the 50th congress of the ISAE. Importantly, postgraduate students and non-permanent jobholders said they wanted to continue activities that they started during the lockdown and could play a crucial role in both participating and organising such activities.

4.2. Favour formal interactions with peers to scaffold worries about the future and career progression in potentially vulnerable sub-populations

In our survey, postgraduates, ECRs, and non-permanent jobholders reported worrying about future availabilities of positions (academic and non-academic) significantly more than others. This is not surprising, as the pandemic has caused great economic losses resulting in dramatic changes in academia (e.g.Witze, 2020; Woolston, 2020a). This development is especially worrisome for ECRs who have not secured a position yet (Woolston, 2020b). Moreover, the abrupt halt of experiments resulting in reduced research productivity puts ECRs in a difficult position as they were already pressured to produce high research outputs to advance their careers (Denfeld et al., 2020; Woolston, 2020a; Levine and Rathmell, 2020). ECRs’ worries about the future is a serious issue to tackle, since a high level of work-related stress can result in mental health problems (Melchior et al., 2007), and postgraduates were already shown (pre−COVID-19 studies) to be ten times more likely to have anxiety and depression symptoms than the general public (e.g.Evans et al., 2018). Social relationships, both private and professional, emerged as key factors in coping with lockdown challenges (Nitschke et al., 2020). Postgraduates and ECRs would thus benefit from regular personal exchanges with peers and mentors, enabling them to network within and outside academia and to discuss career options, which could ease the stress and worries regarding their career (Wang and DeLaquil, 2020). Developing/reinforcing scientific networks and societies’ mentoring schemes and activities, such as the ASAB Networking in the Animal Behaviour Sciences (Benvenuto et al., 2020) and the ISAE 2020 Global Virtual Meeting supporting ECR workshop; also appears very timely. Likewise, within-career level supporting activities could be encouraged, as being exposed to a wider range of both successes (setting up goals to reach themselves) and difficulties faced by others (which are often similar across people) ultimately boosts ECRs self-confidence and resilience (Earvolino-Ramirez, 2007; Denfeld et al., 2020).

Contrary to our predictions, ABW respondents were also more likely to report worries about the future than respondents from the other sampled research disciplines. This result partially aligns with the findings from Myers et al. (2020) showing that ‘bench sciences’ can face greater disruptions than other disciplines. Indeed, while the ABW discipline fits into the ‘bench science’ disciplines, a large proportion (i.e. 37%) of our ‘not ABW’ sampled respondents also worked in other ‘bench sciences’ disciplines. The ‘bench science’ effect may therefore contribute to, but is unlikely to fully explain, our own results. The change in funding landscape overall, cuts from charity funding bodies, and research on COVID-19 being favoured, might challenge ABW research. ECRs of other disciplines for instance questioned whether changing research focus from ‘non-essential’ to pandemic research is necessary for career progress in this new reality (Denfeld et al., 2020), and ABW researchers might worry that their field does not offer the opportunity to adapt to this new emergent research focus. Besides, the cessation of experiments resulted in the culling of laboratory animals (Nowogrodzki, 2020; Tremoleda and Kerton, 2020), and Covid-19 had a devastating impact on farm animals’ welfare (Marchant-Forde and Boyle, 2020), which could have presented an emotional burden to researchers. Such emotional hardships, together with research concerns such as working with some animal models that will take time and money to re-establish, might have reduced resilience of ABW respondents, and contributed to their greater concerns about the future. However, integrative perspectives considering human, animal and environmental health together (e.g. One Health) are essential to face future challenges (e.g.Marchant-Forde and Boyle, 2020; Parry, 2020; Salkeld, 2020; Trivedy, 2020), and ABW researchers can certainly play an important role in reinforcing these integrative approaches which may offer some consolation and motivation as they consider future prospects. Research networks, such as UK Animal Welfare Research Network and the French Society for the study of Animal behaviour SFECA, bring together researchers and stakeholders with interests in animal behaviour and welfare, and could for instance prove very useful in creating opportunities for transdisciplinary collaborations. Furthermore, just as this special issue aims to, the pandemic situation offers ABW researchers the unprecedented opportunity to reflect on our own confinement experiences to better empathize with non-human animals in confinement, and to generate future applied and fundamental research suggestions.

4.3. Moving Forward: recognising inter-individual differences when creating a suitable working environment

The variability in our respondents’ replies might reveal opportunities for long-term improvements, especially in terms of work routine and work-life balance. For instance, the forced move into home-office due to lockdown has proven difficult for some people, whilst others adapted quickly to working from home. Difficulties in adapting to working from home might have related to some home-office setups failing to provide the necessary resources for successful task performance, for example due to physical (e.g. inadequate thermal comfort, lighting, and noise) and/or social (e.g. shared spaces, disruption from other household members) characteristics of the work space (Roberts et al., 1997). Dissatisfaction with a work environment can be associated with headaches and decreased concentration (Wyon, 2004), reduced work motivation (Lan et al., 2010), and negative mood (Lamb and Kwok, 2016). Moreover, clear boundaries between work and home are important for psychological detachment, which can lower stress and exhaustion (Sonnentag, 2012; Sonnentag and Fritz, 2007). However, people have different preferences for integrating or separating work and home (Nippert-Eng, 1996), and work efficiency may be influenced by personality traits (Camerlink et al., this issue). ‘Segmenter’ type people prefer to leave ‘work at work’ and can suffer from the convergence of workplace and private space, as illustrated by one of our respondents commenting that ‘it feels more like I am living at work than working from home’. Conversely, respondents who quickly adapted to remote working might belong to the ‘integrator’ type, who prefer blending their home and work life. Some respondents also stated that they had more time for personal activities since commuting became unnecessary. Having greater flexibility in daily routine and working hours was reported as an asset in working from home. This might be especially important considering different preferences in sleep/wake times (i.e. early/late chronotypes) as circadian misalignment (‘social jetlag’) has been associated with chronic health conditions and psychological well-being (Wittmann et al., 2006; Foster, 2020). Recognising further inter-individual differences between ‘segmenters’ who need to be flexibly allowed to go back to their office space, and ‘integrators’ who could benefit from longer term arrangement in terms of part- or full-time remote working, is one of the positive changes academic employers could embrace at present, and in future.

Against our expectations, we found no gender effect on reported experiences, except that female respondents reported more personal changes affecting their ability to work than male respondents. Other personal circumstances (e.g. career level, care responsibilities regardless of gender, and personality traits, see Camerlink et al., this issue) might have had greater impact on experiences than gender taken alone. Nonetheless, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated already-existing gender inequities in academia (Malisch et al., 2020; Guy and Arthur, 2020; Gabster et al., 2020), which urges the need to prioritise practices promoting better gender balance.

5. Conclusion

The lockdown period has presented a challenging situation to researchers with regards to their work but also personal life. The results of our survey highlighted that these challenges cannot be generalised as individuals differed in their experiences and coping strategies. However, a lack of informal contact with colleagues, a loss of focus due to worry or stress, and unsuitable working environments were the most commonly perceived adverse effects associated with lockdown. Postgraduate students and research associates, and non-permanent jobholders, reported more challenges than their counterparts. In addition, ABW researchers reported more worries concerning their future compared to researchers from other disciplines. Our results do not demonstrate a gender effect on experiences during the lockdown, but current literature urges the need to prioritise practices promoting better gender balance. Despite challenges, most respondents have also perceived some positive changes affecting work or/and personal life suggesting that these unprecedented times also hold opportunities for positive change. We discussed suggestions for mitigating some of these challenges, which include favouring both informal and formal interactions with peers and recognising further inter-individual differences to adapt the work environment; in order to build a more resilient research community.

Funding

C. Fureix acknowledges support from BBSRC grants BB/S012974/1 and BB/P019218/1.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our colleagues who helped with piloting the questions and respondents for participating in our survey. We thank Poppy Statham for her help with online survey tool and distribution of the survey via the AWRN newsletter, and Rebecca Waghorne from the University of Plymouth Science and Engineering Human Ethics Committee for quickly processing our application.

Footnotes

This paper is part of the Special Issue 'COVID-19: Rethinking confinement' based on the 2020 ISAE conference.

Percentages do not add up to 100% in this question as people could tick all that apply and report e.g. a change in taking more work and taking more personal responsibilities, or taking both more personal responsibilities and personal activities, etc.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105269.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Benjamini Yoav, Liu Wei. A step-down multiple hypotheses testing procedure that controls the false discovery rate under independence. J. Stat. Plan. Inference. 1999;82(1–2):163–170. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3758(99)00040-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuto Chiara, Farine Damien, Frasnelli Elisa, Healy Susan, Madden Joah, Monoghan Pat, Williams Ellen. 2020. ASAB Networking.https://www.facebook.com/ASABNews/photos/pb.1427927124109495.-2207520000./2856201151282078/?type=3&theatre (Accessed 12/11/2020) [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo John T., Hawkley Louise C., Norman Greg J., Berntson Gary G. Social isolation: social isolation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011;1231(1):17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camerlink Irene, Nielsen Birte L., Windschnurer Ines, Vigors Belinda. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on animal behaviour and welfare researchers. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105255. (submitted to this issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron Kenzie A., Daniels Lauren A., Traw Emily, McGee Richard. Mentoring in crisis does not need to put mentorship in crisis: realigning expectations. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020;(July):1–2. doi: 10.1017/cts.2020.508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaburu Dan S., Harrison David A. Do peers make the place? conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008;93(5):1082–1103. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranford Steven W. I May Not Have Symptoms, but COVID-19 Is a Huge Headache. Matter. 2020;2(5):1068–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.matt.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denfeld Quin, Erickson Elise, Valent Amy, Villasana Laura, Zhang Zhenzhen, Myatt Leslie, Guise Jeanne-Marie. COVID-19: challenges and lessons learned from early career investigators. J. Womens Health. 2020;29(6):752–754. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earvolino-Ramirez Marie. Resilience: a concept analysis. Nurs. Forum. 2007;42(2):73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans Teresa M., Bira Lindsay, BeltranGastelum Jazmin, Weiss L.Todd, Vanderford Nathan L. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36(3):282–284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Antonio Arturo, Shaw GrahamPaul. Academic leadership in a time of crisis: the coronavirus and COVID‐19. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2020;14(1):39–45. doi: 10.1002/jls.21684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster Russell G. Sleep, circadian rhythms and health. Interface Focus. 2020;10(3) doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2019.0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabster Brooke Peterson, Daalen Kimvan, Dhatt Roopa, Barry Michele. Challenges for the female academic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1968–1970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31412-31414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy Batsheva, Arthur Brittany. Academic motherhood during COVID‐19: navigating our dual roles as educators and mothers. Gend. Work Organ. 2020;27(5):887–899. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad Julianne, Smith Timothy B., Baker Mark, Harris Tyler, Stephenson David. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye David W., Underwood Nora, Inouye Brian D., Irwin Rebecca E. Support early-career field researchers. Science. 2020;368(6492):724–725. doi: 10.1126/science.abc1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamerlin, Lynn ShinaCaroline, Wittung-Stafshede Pernilla. Female Faculty: Why So Few and Why Care? Chem. Eur. J. 2020;26(38):8319–8323. doi: 10.1002/chem.202002522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner Ladislav, Horáček Jiří. Three challenges that the COVID-19 pandemic represents for psychiatry. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2020;217(3):475–476. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeze Ella, Popper Nathaniel. 2020. The Virus Changed the Way We Internet. The New York Times. April 7, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/07/technology/coronavirus-internet-use.html. (Accessed 26/10/2020) [Google Scholar]

- Kong Jennifer, Chan Steven. Advice for the worried. Science. 2020;368(6489) doi: 10.1126/science.368.6489.438. 438–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb S., Kwok K.C.S. A longitudinal investigation of work environment stressors on the performance and wellbeing of office workers. Appl. Ergon. 2016;52:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Li, Lian Zhiwei, Pan Li, Li Pan. The Effects of Air Temperature on Office Workers’ Well-Being, Workload and Productivity-Evaluated with Subjective Ratings. Appl. Ergon. 2010;42(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine Ross L., Kimryn Rathmell W. COVID-19 impact on early career investigators: a call for action. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2020;20(7):357–358. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malisch Jessica L., Harris Breanna N., Sherrer Shanen M., Lewis Kristy A., Shepherd Stephanie L., McCarthy Pumtiwitt C., Spott Jessica L., et al. Opinion: In the Wake of COVID-19, Academia Needs New Solutions to Ensure Gender Equity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117(27):15378–15381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010636117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant-Forde Jeremy N., Boyle Laura A. COVID-19 effects on livestock production: a one welfare issue. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020;7(September) doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.585787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior Maria, Caspi Avshalom, Milne Barry J., Danese Andrea, Poulton Richie, Moffitt Terrie E. Work Stress Precipitates Depression and Anxiety in Young, Working Women and Men. Psychol. Med. 2007;37(8):1119–1129. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq Raheel. Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014;8(9) doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828. WE01-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers Kyle R., Yang Tham Wei, Yin Yian, Cohodes Nina, Thursby Jerry G., Thursby Marie C., Schiffer Peter, Walsh Joseph T., Lakhani Karim R., Wang Dashun. Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020;4(9):880–883. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0921-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nippert-Eng Christena. Calendars and Keys: the Classification of ‘Home’ and ‘Work.’. Sociol. Forum. 1996;11(3):563–582. doi: 10.1007/BF02408393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke Jonas P., Forbes Paul A.G., Ali Nida, Cutler Jo, Apps Matthew A.J., Lockwood Patricia L., Lamm Claus. Resilience during uncertainty? Greater social connectedness during COVID‐19 lockdown is associated with reduced distress and fatigue. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020;12485(October) doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowogrodzki Anna. Cull, release or bring them home: coronavirus crisis forces hard decisions for labs with animals. Nature. 2020;580(7801) doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00964-y. 19–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleschuk Merin. Gender equity considerations for tenure and promotion during COVID‐19. Can. Rev. Sociol. Can. Sociol. 2020;57(3):502–515. doi: 10.1111/cars.12295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry Nicola M.A. COVID-19 and Pets: When Pandemic Meets Panic. Forensic Science International: Reports. 2020;2(December) doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul Karsten I., Moser Klaus. Unemployment impairs mental health: meta-analyses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009;74(3):264–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts James A., Lapidus Richard S., Chonko Lawrence B. Salespeople and stress: the moderating role of locus of control on work stressors and felt stress. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1997;5(3):93–108. doi: 10.1080/10696679.1997.11501773. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salkeld Dan. One health and the COVID‐19 pandemic. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2020;18(6) doi: 10.1002/fee.2235. 311–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelius Jae M., Gutierrez-Mock Luis, Zamudio-Haas Sophia, McCree Breonna, Ngo Azize, Jackson Akira, Clynes Carla, et al. Research with marginalized communities: challenges to continuity during the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(7):2009–2012. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02920-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn Emily. The pressures of a scientific career can take their toll on people’s ability to cope. Nature. 2016;539(321):3. doi: 10.1038/nj7628-319a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag Sabine. Psychological detachment from work during leisure time: the benefits of mentally disengaging from work. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012;21(2):114–118. doi: 10.1177/0963721411434979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag Sabine, Fritz Charlotte. The recovery experience questionnaire: development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007;12(3):204–221. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnyk Tricia, Black Kerry. Lost ground: female academics face an uphill battle in post‐pandemic world. Hydrol. Process. 2020;34(15):3400–3402. doi: 10.1002/hyp.13803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staniscuaski Fernanda, Reichert Fernanda, Werneck Fernanda P., de Oliveira Letícia, Mello-Carpes P.âmela B., Soletti Rossana C., Almeida Camila Infanger, et al. “Impact of COVID-19 on academic mothers.” edited by jennifer sills. Science. 2020;368(6492):724. doi: 10.1126/science.abc2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens Keri K., Jahn Jody L.S., Fox Stephanie, Charoensap-Kelly Piyawan, Mitra Rahul, Sutton Jeannette, Waters Eric D., Xie Bo, Meisenbach Rebecca J. Collective sensemaking around COVID-19: experiences, concerns, and agendas for our rapidly changing organizational lives. Manag. Commun. Q. 2020;34(3):426–457. doi: 10.1177/0893318920934890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tremoleda Jordi L., Kerton Angela. Creating space to build emotional resilience in the animal research community. Lab Anim. (NY) 2020;49(10):275–277. doi: 10.1038/s41684-020-0637-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedy Chet. Is 2020 the Year When Primatologists Should Cancel Fieldwork? A Reply. Am. J. Primatol. 2020;82(8) doi: 10.1002/ajp.23173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Lizhou, DeLaquil Tessa. The isolation of doctoral education in the times of COVID-19: recommendations for building relationships within person-environment theory. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020;39(7):1346–1350. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1823326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann Marc, Dinich Jenny, Merrow Martha, Roenneberg Till. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol. Int. 2006;23(1–2):497–509. doi: 10.1080/07420520500545979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witze Alexandra. Even after the worst of the coronavirus pandemic passes, its effects could permanently alter how scientists work, what they study and how much funding they receive. Nature. 2020;582:162–164. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01518-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolston Chris. Junior researchers hit by coronavirus-triggered hiring freezes. Nature. 2020;582(7812):449–450. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolston Chris. Pandemic darkens postdocs’ work and career hopes. Nature. 2020;585(7824):309–312. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02548-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyon D.P. The effects of indoor air quality on performance and productivity: the effects of IAQ on performance and productivity. Indoor Air. 2004;14(Suppl 7):92–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki Jamil, Craig Williams W. Interpersonal emotion regulation. Emotion. 2013;13(5):803–810. doi: 10.1037/a0033839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.