Abstract

Background: Sexual assault (SA) is common, but Black individuals might be at higher risk of SA and negative health sequalae. Racial differences in SA characteristics and health care utilization after SA are largely unknown.

Materials and Methods: We reviewed medical records of 690 individuals (23.9% Black; 93.6% women) who received a SA medical forensic exam (SAMFE) at a southeastern U.S. hospital. We examined bivariate racial differences in SA characteristics and used zero-inflated Poisson regressions to estimate racial differences in mental health outpatient visits at the SAMFE hospital.

Results: Among survivors of SA, Black survivors were more likely than White survivors to have been victimized by an intimate partner (odds ratio [OR] = 1.77, confidence interval [95% CI] = 1.02–3.07) and they had more post-SA outpatient mental health visits at the SAMFE hospital (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.70–2.47). Black survivors were less likely to report alcohol or drug use before the SA (OR = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.28–0.62). In multivariable models, Black survivors trended toward more mental health visits than White survivors (IRR = 1.63, 95% CI = 0.82–2.44), but intimate partner violence (IPV) significantly moderated that association (IRR = 0.01, 95%CI = ≤0.001–0.03). Black survivors assaulted by an intimate partner were less likely to access mental health care than White IPV survivors.

Conclusions: The hospital setting of a SAMFE could be a unique opportunity to serve Black survivors and reduce racial disparities in mental health sequelae, but additional support will be needed for Black survivors experiencing IPV. An intersectional, reproductive justice framework has the potential to address these challenges.

Keywords: sexual assault, sexual violence, sexual assault medical forensic exams, racial disparities, mental health care, intimate partner violence

Introduction

While sexual violence against women is ubiquitous across race, ethnicity, class, and nationality, some evidence suggests Black* women are at increased risk of sexual victimization and negative health sequelae compared with White women.1–3 Sexual violence is broadly defined as aggressive behaviors of a sexual nature, including rape (i.e., any completed or attempted unwanted vaginal, oral, or anal penetration through the use of physical force or threats), unwanted sexual contact (e.g., forced penetration, unwanted fondling), and noncontact unwanted sexual experiences (e.g., verbal harassment) acts.4

Rates and prevalence of sexual violence differ by sample, method of data collection, and type of sexual violence with some studies suggesting Black women experience higher risk of sexual violence in their lifetime, while others suggest similar rates of sexual violence between White and Black women.1–4 For example, Kilpatrick et al.'s national telephone survey found 23.4% of Black women had been raped in their lifetime compared with 15.4% of White women, but the authors noted this was inconsistent with previous studies that found similar prevalence by race/ethnicity.5 Research indicates that several risk factors associated with sexual violence disproportionally impact Black women, such as poverty and child sexual abuse, and these likely contribute to sexual vulnerability as well as long-term health consequences are linked with sexual victimization.1,2

Evidence more consistently shows that Black women are at higher risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV following sexual violence.1,2 One area of research has focused on racial differences in disclosure and social support, which could explain some of the racial health inequities among sexual violence survivors.6 For example, Black people are more likely to experience or witness police brutality, so Black survivors must navigate their own concerns about and distrust of police in addition to community pressure to not engage with police due to concerns of safety.7

Compared with White women, Black women also tend to experience more negative social reactions when disclosing sexual violence, particularly among formal support providers (e.g., police, medical personnel).6,8 Negative reactions to disclosure are, in turn, associated with higher risk of PTSD among Black women.8 These negative experiences with formal and informal supports following sexual victimization may discourage women from seeking care. This highlights the need for evidence-based practices that are structurally competent, culturally tailored, and trauma informed.

Medical and mental health care following sexual violence can reduce the risk of long-term mental and physical health consequences, but structural racism within health systems impedes access to effective, appropriate care for Black survivors. Cognitive behavioral therapy and cognitive processing therapy have been shown to decrease symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD, and may reduce risk of revictimization among women survivors.9,10 Yet there is consistent evidence of barriers to mental health care services for Black women stemming from mental health stigma, financial inequities, and mistrust of providers due to experiences of racism.11–13

The U.S. healthcare system as well as legal system have enduring historical legacies of oppression toward Black women, and these interlocking systems of oppression are intimately tied to Black women's postassault responses (i.e., mental and physical health care, legal action).12,14 Indeed, Bryant-Davis et al. note that trauma experiences, including sexual violence, must be contextualized in research by considering sociocultural factors that involve both race and gender to more readily understand racial disparities in mental health care in the United States.14 Therefore, further research is needed examining differences in postsexual assault (SA) experiences of Black and White women survivors that takes into account sociocultural contexts.

There are limitations to the scientific knowledge in terms of differences in SA characteristics by race, including relationship to perpetrators, use of weapons, alcohol, and drug involvement, and injuries. It is also unclear how access to mental health care following SA might differ by race. Our current study addresses these gaps in our understanding of sexual violence and asks:

- 1.

How do experiences of SA differ by race among survivors who receive a SA medical forensic exam (SAMFE)?

- 2.

How does utilization of mental health care following SA differ by race?

- 3.

Are racial differences in post-SAMFE mental health care moderated by characteristics of the SA?

Materials and Methods

Procedure

The current study used a retrospective cohort design. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board before data access, and all participants consented to the use of their medical records for research. Following study approval, the electronic medical records of a large academic medical center in the southeastern United States were accessed for all individuals age 18 or older receiving a SAMFE within 120 hours of the assault between July 1, 2014 and May 15, 2018. For the small minority of individuals who received multiple SAMFEs during this period, we restricted analyses to their first examination. Demographic information was obtained directly from the electronic medical record and paired with the SA Nurse Examiner notes, described below. After pairing, individual medical record numbers were replaced by randomly generated personal identification numbers to protect confidentiality.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic information, including race/ethnicity, gender, and age at time of visit were acquired directly from each participant's electronic medical record. Notably, because this study is focused on racial differences in SA and follow-up care, we restricted the sample to only non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black survivors. Race and ethnicity were not self-reported, but rather determined by the provider. For this reason, 0.00% of files had missing data on race and only 0.32% of files had missing data on ethnicity.

SA characteristics

SA information was recorded by the SA Nurse Examiner in the emergency department at the time of the SAMFE. These characteristics included report of weapon use by the perpetrator during the assault (yes/no); alcohol or drug use by the patient or perpetrator before, during, or after the assault (yes/no); whether the assault was perpetrated by an intimate partner (yes/no); vaginal (yes/no) or anal penetration (yes/no); whether the patient was strangled during the assault (yes/no); and the presence and type of injury (vaginal, anal, and nongenital).

Mental health visits

Visits to the same medical center for mental health appointments within a year following SAMFE were collected directly from each participant's electronic medical record. This was measured as a count variable.

Sample demographics

The sample (Table 1) comprised 690 individuals (93.62% female, 6.38% male) ranging from age 18 to 76 (M = 29.27 years, SD = 10.7). Survivors in this sample identified as non-Hispanic White (n = 525; 76.09%) or non-Hispanic Black/African American (n = 165; 23.91%).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Sample of Sexual Assault Survivors from Forensic Exams at a Southeastern U.S. Hospital (n = 690)

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 165 | 23.91 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 525 | 76.09 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 646 | 93.62 |

| Male | 44 | 6.38 |

| Age | ||

| <21 years | 151 | 21.88 |

| 21–25 years | 181 | 26.23 |

| 26–35 years | 205 | 29.71 |

| 36 years+ | 153 | 22.17 |

| Weapon used | 53 | 8.75 |

| Alcohol or drugs present | 381 | 62.98 |

| Intimate partner violence | 67 | 11.75 |

| Vaginal penetration | 391 | 86.70 |

| Anal penetration | 83 | 19.76 |

| Strangulation | 60 | 9.88 |

| Any injury | 379 | 62.96 |

| Vaginal injury | 171 | 28.98 |

| Anal injury | 34 | 5.72 |

| Genital injury | 190 | 32.09 |

| Nongenital injury | 296 | 48.60 |

| Mental health outpatient visits | ||

| 0 | 634 | 91.88 |

| 1 | 12 | 1.74 |

| 2 | 8 | 1.16 |

| 3 or more | 36 | 5.22 |

Analyses

We first analyzed racial differences in the characteristics of SA in our sample. We used chi-square analyses to test for statistically significant differences between Black and White survivors in weapon use and alcohol/drug use during SA. We then used bivariate Poisson regression15 to assess unadjusted racial differences in the number of mental health care visits. Next, we used zero-inflated Poisson regression models15 to measure racial differences in the number of mental health visits a patient received at the hospital, after controlling for covariates: sex, age, weapon use during SA, alcohol/drug use during SA. Finally, we tested an interaction term between race and weapon use to test if weapon use moderated the relationship between race and number of mental health care visits.

Notably, age was measured in the records as continuous, but we reclassified using a categorical variable of <21, 21–25, 26–35, or 36+ years for multivariable analyses. We used a dichotomous variable of <26 and 26+ years for bivariate analyses to improve data visualization. We conducted sensitivity analyses to test for age differences by race using the continuous, categorical, and dichotomous variables in the bivariate and multivariable models. Analyses were conducted using Stata v.1416 and MPlus v.8.1.7.17

Results

SA characteristics and post-SAMFE mental health care visits

In the full sample, about 9% (n = 53) of survivors had a weapon used against them during the SA. Nearly 63% (n = 381) of survivors reported drug or alcohol use by themselves or their perpetrator before, during, or after the assault (see Table 1). About 12% (n = 67) of SAs were perpetrated by an intimate partner. Most of the assaults (87%, n = 391) involved vaginal penetration, whereas about 20% involved anal penetration (n = 83). Approximately 10% (n = 60) of survivors reported being strangled during the assault. Nearly 63% (n = 379) of survivors were injured in the course of the assault, including 29% (n = 171) who were injured vaginally, 6% (n = 34) injured anally, and 49% (n = 296) who sustained bodily injuries. In the full sample, 92% (n = 634) of survivors never returned to the hospital for mental health care services, 2% (n = 12) returned for 1 visit, 1% returned for 2 visits (n = 8), and 5% (n = 36) returned for 3 or more visits.

Racial differences in SA characteristics

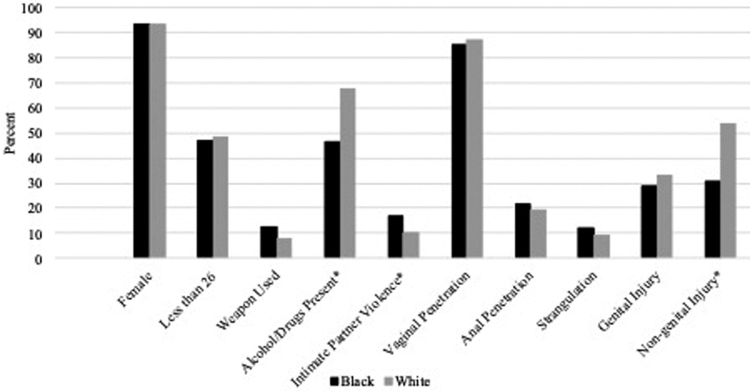

We found significant differences in SA characteristics across Black and White survivors (Table 2 and Fig. 1). First, Black survivors had 1.77 times the odds of White survivors to experience SA by an intimate partner (17% vs. 10%, odds ratio [OR] = 1.77, confidence interval [95% CI] = 1.02–3.07). Second, Black survivors were significantly less likely to have alcohol or drug use involvement in the assault (47% vs. 68%, OR = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.28–0.62). Third, while there were no racial differences in genital (vaginal or anal) injury, Black survivors were significantly less likely to experience bodily injury than White survivors (31% vs. 54%, OR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.25–0.57). There were no significant racial differences in sex or age of the patient nor were there significant racial differences in weapon use or experience of vaginal penetration, anal penetration, or strangulation.

Table 2.

Bivariate Statistics of White and Black Sexual Assault Survivors from Sexual Assault Forensic Exams at a Southeastern U.S. Hospital (n = 690)

| Variable | Black | White | IRR/OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |||

| Female | 154 | 93.33 | 492 | 93.71 | 1.06 | 0.53–2.16 |

| <26 Years old | 78 | 47.27 | 254 | 48.38 | 0.96 | 0.67–1.36 |

| Weapon used | 17 | 12.69 | 36 | 7.63 | 1.76 | 0.95–3.24 |

| Alcohol or drugs present* | 62 | 46.62 | 319 | 67.58 | 0.42 | 0.28–0.62 |

| Domestic violence* | 22 | 16.79 | 45 | 10.25 | 1.77 | 1.02–3.07 |

| Vaginal penetration | 87 | 85.29 | 304 | 87.11 | 0.86 | 0.46–1.61 |

| Anal penetration | 21 | 21.43 | 62 | 19.25 | 1.14 | 0.66–1.99 |

| Strangulation | 16 | 11.94 | 44 | 9.3 | 1.32 | 0.72–2.43 |

| Any injury* | 65 | 48.51 | 314 | 67.09 | 0.46 | 0.31–0.68 |

| Vaginal injury | 36 | 27.27 | 135 | 29.48 | 0.90 | 0.58–1.38 |

| Anal injury | 6 | 4.58 | 28 | 6.05 | 0.75 | 0.3–1.84 |

| Genital injury | 38 | 28.79 | 152 | 33.04 | 0.82 | 0.54–1.25 |

| Nongenital injury* | 41 | 30.6 | 255 | 53.68 | 0.38 | 0.25–0.57 |

| Mental health outpatient visits | Mean = 1.10 | 25% = 0 | Mean = 0.54 | 25% = 0 | 2.05 | 1.70–2.47 |

| 95% = 8 | 95% = 2 | |||||

Statistical significance p < 0.05.

CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio; OR, odds ratio.

FIG. 1.

Black–White differences in characteristics of sexual assault survivors from sexual assault forensic exams at a southeastern U.S. hospital (n = 690). *Statistical significance p < 0.05.

Racial differences in post-SAMFE mental health care visits

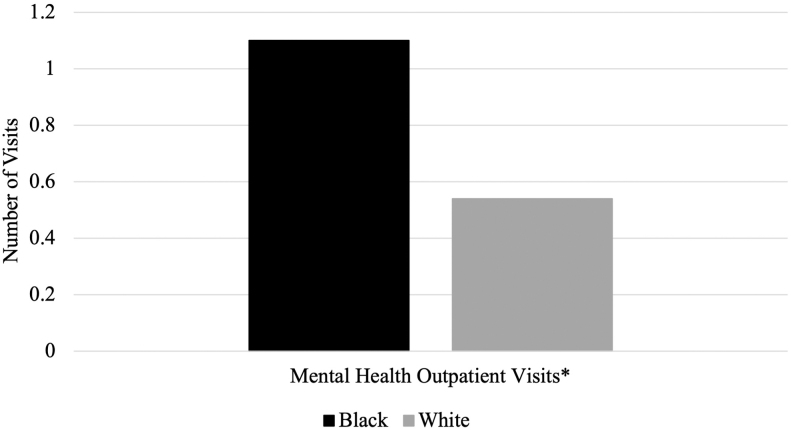

We also found significant racial differences in mental health care outpatient visits 1 year after the SAMFE. At the bivariate level (Table 2 and Fig. 2), Black survivors had more outpatient mental health care visits than White survivors after the SA (M = 1.10 vs. 0.54, incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 2.05, 95% CI = 1.70–2.47). In the multivariable zero-inflated Poisson regression analyses adjusting for sex, age, weapon use, and alcohol/drug involvement (Table 3), Black race trended toward a higher number of mental health compared with White survivors (IRR = 1.63, 95% CI = 0.82–2.44), but not whether or not the patient received any mental health care at the hospital (IRR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.35–1.65).

FIG. 2.

Black–White differences in mental health care among sexual assault survivors following sexual assault forensic exams at a southeastern U.S. hospital (n = 690). *Statistical significance p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Zero-Inflated Poisson Regression Models of Sexual Assault Characteristics and Mental Health Care Among a Sample of Sexual Assault Survivors at a Southeastern U.S. Hospital (n = 690)

| Model | Variable | Mental health follow-up visits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR/OR | 95% CI | |||

| Poisson | Black | 1.63 | 0.82 | 2.44 |

| Male | 0.37 | <0.001 | 0.74 | |

| Age (Ref.: younger than 21) | ||||

| 21–25 | 1.14 | 0.32 | 1.96 | |

| 26–35 | 1.01 | 0.22 | 1.79 | |

| 36 or older* | 3.59 | 1.01 | 6.16 | |

| Weapon used | 1.51 | 0.51 | 2.52 | |

| Alcohol or drugs present* | 2.53 | 1.08 | 3.98 | |

| Domestic violence* | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.12 | |

| Genital injury* | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.79 | |

| Nongenital injury* | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.39 | |

| Zero-inflation Logit | Black | 1.00 | 0.35 | 1.65 |

| Male | 4.60 | <0.001 | 14.62 | |

| Age (Ref.: younger than 21) | ||||

| 21–25 | 0.65 | 0.13 | 1.16 | |

| 26–35 | 1.17 | 0.18 | 2.16 | |

| 36 or older | 1.12 | 0.08 | 2.15 | |

| Weapon used | 0.83 | <0.001 | 1.65 | |

| Alcohol or drugs present | 1.58 | 0.50 | 2.65 | |

| Domestic violence | 0.99 | <0.001 | 2.46 | |

| Genital injury | 1.11 | 0.39 | 1.84 | |

| Nongenital injury | 1.33 | 0.52 | 2.14 | |

Statistical significance p < 0.05.

Interaction between race and intimate partner violence on mental health care

We found a significant interaction effect between race and intimate partner violence (IPV) on the number of post-SAMFE mental health care visits (IRR = 0.01, 95% CI = ≤0.001–0.03) (see Table 4). Whereas Black survivors had more mental health care visits than White survivors in bivariate analyses, when the perpetrator of the SA was an intimate partner that association was reversed (IRRBlack vs. White no IPV = 1.63, p = 0.056; IRRBlack vs. White IPV = 0.013, p = 0.566†).

Table 4.

Zero-Inflated Poisson regression Models of Mental Health Care with an Interaction Between Race and Intimate Partner Violence Among a Sample of Sexual Assault Survivors at a Southeastern U.S. Hospital (n = 690)

| Model | Variable | Mental health follow-up visits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR/OR | 95% CI | |||

| Poisson | Black | 1.65 | 0.79 | 2.51 |

| Male | 0.32 | <0.001 | 0.69 | |

| Age (Ref.: younger than 21) | ||||

| 21–25 | 1.34 | 0.18 | 2.49 | |

| 26–35 | 1.13 | 0.05 | 2.22 | |

| 36 or older* | 3.64 | 0.71 | 6.57 | |

| Weapon used | 1.33 | 0.43 | 2.24 | |

| Alcohol or drugs present* | 2.46 | 0.88 | 4.04 | |

| Domestic violence* | 0.17 | <0.001 | 0.43 | |

| Black × domestic violence* | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.03 | |

| Genital injury* | 0.45 | 0.14 | 0.76 | |

| Nongenital injury* | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.47 | |

| Zero-inflation Logit | Black | 0.87 | 0.29 | 1.45 |

| Male | 4.37 | <0.001 | 13.96 | |

| Age (Ref.: younger than 21) | ||||

| 21–25 | 0.67 | 0.13 | 1.22 | |

| 26–35 | 1.22 | 0.18 | 2.27 | |

| 36 or older | 1.15 | 0.07 | 2.23 | |

| Weapon used | 0.83 | 0.02 | 1.64 | |

| Alcohol or drugs present | 1.58 | 0.51 | 2.64 | |

| Domestic violence | 0.78 | <0.001 | 2.05 | |

| Black × domestic violence | 0.77 | <0.001 | 3.92 | |

| Genital injury | 1.05 | 0.37 | 1.73 | |

| Nongenital injury | 1.30 | 0.51 | 2.10 | |

Statistical significance p < 0.05.

Descriptive statistics of the subsamples suggest Black survivors of a SA perpetrated by an intimate partner accessed fewer post-SAMFE mental health care visits (M = 0.05, 25% = 0, 95% = 0) than other Black survivors (M = 1.43, 25% = 0, 95% = 12) or all White survivors (MWhite no IPV = 0.61, 25% = 0, 95% = 4; MWhite IPV = 0.49, 25% = 0, 95% = 4). Moreover, these suggest that for White survivors, having a perpetrator who was an intimate partner did not influence the number of post-SAMFE mental health outpatient visits.

Discussion

The primary aims of the current study were to examine racial differences in SA characteristics and utilization of postassault mental health care. We also tested whether racial differences in mental health care utilization were moderated by SA characteristics. These questions were investigated using a retrospective cohort design in a large sample of 690 non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black adults who received a SAMFE exam at an academic medical center.

First, we found that IPV reversed the positive association between Black race and number of mental health care visits in the year following the assault. Black survivors had a significantly lower number of mental health care visits if they were assaulted by their intimate partner as compared with White survivors or to Black survivors who were assaulted by non-intimate acquaintances or strangers. Other notable racial differences emerged with regard to SA characteristics. For one, Black survivors were more likely than White survivors to be assaulted by an intimate partner and were less likely to sustain bodily injuries during the SA. Second, White survivors were significantly more likely to report alcohol or drug involvement. Third, Black survivors attended a greater number of outpatient mental health visits in the year following the assault than White survivors. This effect was attenuated after controlling for sex, age, weapon use, alcohol/drug involvement, IPV, and injuries.

These findings must be carefully situated in existing evidence of racial disparities in SA and IPV within the structural contexts of intersectional oppression. Some previous research has suggested Black women might be at increased risk of sexual violence and IPV.2,18,19 Our results echo these findings by showing that Black survivors receiving SAMFE were more likely than White survivors to have been assaulted by an intimate partner. These disparities must be placed into appropriate context, namely the intersectional oppression of Black women,‡18–20 including racialized and gendered poverty—wherein Black individuals, and particularly Black women, are more likely to live in poverty because of structural racism and sexism, such as discrimination in education, employment, and housing.21

In American society, Black women experience sexism, racism, economic oppression, and sexual and reproductive oppression simultaneously.18,19,22–24 Our study found that Black survivors who were assaulted by an intimate partner were significantly less likely to access post-SAMFE at the hospital. Perhaps this is because they may be both hypersexualized and blamed for their own sexual victimization18,24—for example, the “Jezebel” stereotype—and expected to be strong, resilient, and responsible in the face of unsurmountable inequality and disadvantage—the “Sojourner Truth Syndrome.”25 Altogether, these double binds require that Black women—like the survivors in our study—navigate both increased risk of sexual and IPV and the social effects of structural racism, including mass incarceration, which disproportionately affects and destabilizes Black communities.22

Due to multilevel factors like those structural inequities described above as well as community-level and internalized stigma and mistrust, Black women are less likely than White counterparts to report experiences of SA to authorities18 and less likely to see mental health care for sexual or IPV.19,26 In our study, we actually found that post-SAMFE mental health care at the hospital was being utilized more often by Black survivors than White survivors, perhaps because White survivors sought health care outside the hospital setting. Nevertheless, this highlights hospital-based mental health care as a unique opportunity to diminish racial/ethnic disparities in postsexual violence treatment and support.

At baseline, stigma against mental health care is a major barrier for individuals who experience violence and trauma, particularly in the Black community, at least in part because of medical mistrust and negative experiences with the health care system.11,12 For example, Black communities have been historically exploited for scientific and medical research, including 20th century eugenics campaigns that pathologized poverty as an inheritable mental illness.27 The lack of culturally appropriate (i.e., developed by and for Black people) and structurally competent (e.g., acknowledging structural racism, sexism, homophobia, and economic disadvantage) care further compounds mental health disparities following SA.7,11–13 In response, Black survivors of violence have developed and are more likely to rely on informal and spiritual sources of social support following traumatic events.19,26

At the same time, our results further suggest that when perpetrators are intimate partners, Black survivors are significantly less likely to follow-up for mental health care. Although more research is needed to better understand the mechanisms that account for this effect, it may be due to the sociocultural and psychological challenges Black women face when they are sexually victimized by Black men they know or who are intimate partners. Gómez proposes a “cultural betrayal trauma theory” to conceptualize how “intracultural pressure,” simultaneously coupled with loss of “intracultural trust,” prevents Black women from reporting intraracial sexual violence or seeking care.7 However, the current study did not include information on the race of the perpetrator, and there were not enough men in the study to examine race by gender interactions. Therefore, more research is needed.

Founded by Black women, who are survivors of intimate, sexual, and incestual violence within the Black community, the reproductive justice movement similarly provides a well-suited framework for understanding and addressing these intersectional challenges at the sociostructural levels.23 Put simply, “[a]ddressing the racial and socioeconomic inequities that deny… reproductive justice will also reduce instances of violence and help victims escape their abusive relationship.”28 Culturally appropriate mental health care interventions are needed post-SAMFE that can encourage survivors to seek and maintain mental health care treatment. At the same time, structural interventions are also needed that reduce racialized poverty and discrimination.

At the “2019 Let's Talk About Sex Conference” in Atlanta, reproductive justice organization SisterSong hosted a plenary “Accountability Panel” on intersections of the #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter movements. Panelists including Kenyette Barnes (cofounder of the #MuteRKelly movement) emphasized the need for reproductive justice approaches to sexual and IPV in Black communities that simultaneously acknowledge historical reproductive racism (e.g., rape during slavery), ongoing socioeconomic inequality for Black communities (e.g., lack of living wage jobs and class instability), sexual oppression and stereotyping of Black women, and police brutality and mass incarceration of Black men and women.18,29,30

Applying this framework to our current study implies that (1) post-SAMFE mental health care providers need to be trained in critical medical history31; (2) hospitals need to assess and address their own diversity, equity, and inclusion practices both at the clinical and institutional levels; (3) hospitals could partner with other institutions to address social determinants of health32; and (4) hospitals need clear protocols for the provision of post-SAMFE mental health care that does not trigger engagement with the criminal justice system.

The “Accountability” panelists and other reproductive justice advocates have called for “transformational justice,” an abolitionist framework that seeks justice for survivors of sexual violence in ways that do not rely on or reinforce structural racism inherent to the U.S. justice system.33 Grounded in the assertion that gender-based violence and state violence are interconnected, a “transformational” approach emphasizes primary prevention of the root causes of violence, including racialized economic deprivation, disruption of communities, and support networks through mass incarceration, and misogynoir gender socialization.30,33,34

Our findings from the current study are notable and useful for several reasons. First, the dataset comprised a large, cohort-based sample of survivors who sought emergency department services postassault at a large southeastern academic medical center. SA and demographic characteristics were documented by SAMFE nurse examiners, enabling the collection of clinical data from a critical point in time postassault, and minimizing recall bias that might affect the accuracy of more retrospective study methods. The large size of the sample enabled the study of racial differences within this population, which have been previously understudied in the field of sexual violence. Finally, mental health care visits in the year following the assault were also available in the electronic medical record, which allows for the testing of hypotheses about postassault service utilization.

Despite these notable strengths, the findings from the current study should be interpreted in the context of several important limitations. First, because the data are observational, causality cannot be inferred. Second, because data were collected as part of routine clinical care, some variables relating to participant demographics and SA characteristics were limited. For example, information about survivors' socioeconomic status. Therefore, our results on racial differences likely reflect underlying socioeconomic differences in our sample that were unobserved in the study. Future research should incorporate these socioeconomic variables as potential moderators of the findings reported here. Disentangling racial differences from socioeconomic differences will be imperative for understanding and appropriately addressing SA in difference communities, because racial and economic disadvantage/privilege may impact exposure to violence and access to resources, including mental health care.

Moreover, race was not self-reported but rather based on provider perceptions then recorded in the electronic medical record. It is possible the races of some survivors were misclassified. Third, mental health care visits in the current sample were limited to those in the academic medical center system where data collection occurred. It could be that some participants, such as those with higher socioeconomic status, or those who lived in rural locations where travel to the academic medical center was difficult or inconvenient, might have been more likely to seek mental health care outside of that hospital system.

Our sample is also predominantly women survivors, which limits our ability to make extrapolations about the experiences of men, and data were not available for self-identified gender. Further research is needed to increase understanding of and solutions to disproportionate risk of SA among Black men and—particularly—Black trans women compared with other racial/ethnic and gender groups.20 Finally, although the current study investigated racial differences in SA characteristics and follow-up mental health care, these differences are likely to be the result of underlying racism, racial discrimination, or systematic bias. Future studies should include measures of participants' perceptions of racial discrimination in health care, or other measures of systematic bias in the health care system.

Conclusions

This was a unique study that used data from SAMFE to explore racial disparities in SA characteristics and follow-up care, which are not yet well understood. We found significant racial differences in both the characteristics of SA and the follow-up mental health care after assault. In particular, Black survivors were more likely than White survivors to have been assaulted by an intimate partner, but less likely to have had alcohol/drug involvement or to have sustained nonbodily injuries. Notably, because Black survivors had more mental health follow-up visits at the hospital than White survivors, there is a potential opportunity to mitigate racial disparities in post-SA health outcomes, including higher risk of PTSD and poorer access to mental health care for Black survivors.

This is complicated, however, by the context of IPV. Black survivors who were assaulted by their intimate partner were significantly less likely than other Black survivors to receive follow-up mental health care at the hospital. If hospitals, where survivors receive SAMFE, are to successfully reduce racial disparities in SA outcomes and subsequent mental health care, they will need to attend carefully to those survivors who are experiencing IPV with culturally appropriate and structurally competent care. Further research grounded in the reproductive justice framework and cultural betrayal trauma theory is needed to better understand racial differences in SA characteristics and outcomes, and about ways to develop and improve access to culturally appropriate, structurally competent health care following SA—especially for Black survivors experiencing IPV.

Authors' Contributions

E.A.M.: Conducted analyses, outlined entire article, wrote Results section, Discussion, and Conclusion; coordinated coauthors; edited article; and led submission. J.R.P.: Wrote Introduction; formatted article for the publisher; assisted with revisions. G.B.M.: Cleaned data, wrote Methods and Discussion, edited article, assisted with revisions. S.E.C.: Wrote Introduction, edited article. R.M.L.: Added racial disparities in intimate partner violence evidence and literature, reviewed, and edited article. K.G.-H.: Supervisor of sexual assault forensic exams and data; reviewed and edited entire article. A.K.G.: Study principal investigator, data acquisition, conducted preliminary data analysis, mentored Dr. Mosley, and edited entire article

Copyright Statement

Since G.B.M. is an employee of the U.S. Government and contributed to the article “Racial Disparities in Sexual Assault Characteristics and Follow-Up Care: Results from Sexual Assault Medical Forensics Examinations” as part of her official duties, the work is not subject to U.S. copyright.

Disclaimer

The contents of this article do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

E.A.M.'s contributions are funded by the Mark Chaffin Center for Healthy Development at Georgia State University. Article preparation was partially funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA042935; PI: Gilmore). G.B.M. receives support from the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, the Medical Research Service of the Veterans Affairs Central Virginia Health Care System, and the Department of Veterans Affairs Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC).

In this manuscript, we use the term “Black” to encompass individuals who identify as non-Hispanic Black or African American. “Black” is more inclusive and extends to Black Americans of non-African heritage.

Statistically insignificant results likely reflect insufficient power from a small sample size.

Because this study's sample of sexual assault survivors was 94% female, we are focusing our discussion women. We acknowledge that men also experience sexual assault, and more research is needed about the intersectional experiences of Black male survivors of sexual assault.

References

- 1. Bryant-Davis T, Ullman SE, Tsong Y, Tillman S, Smith K. Struggling to survive: Sexual assault, poverty, and mental health outcomes of African American women. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2010;80:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. West C, Johnson K. Sexual violence in the lives of African American women. National Online Resource Center on Violence Against Women 2013:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coulter RWS, Mair C, Miller E, Blosnich JR, Matthews DD, McCauley HL. Prevalence of past-year sexual assault victimization among undergraduate students: Exploring differences by and intersections of gender identity, sexual identity, and race/ethnicity. Prev Sci 2017;18:726–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith SG, Basile KC, Gilbert LK, et al. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010–2012 state report (cdc:46305). 2017. Available at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/46305 Accessed March 21, 2021.

- 5. Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ, Conoscenti LM, McCauley J. Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study. Charleston, SC: National Criminal Justice Reference Service, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hakimi D, Bryant-Davis T, Ullman SE, Gobin RL. Relationship between negative social reactions to sexual assault disclosure and mental health outcomes of Black and White female survivors. Psychol Trauma 2018;10:270–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gómez J. Group dynamics as a predictor of dissociation for Black victims of violence: An exploratory study of cultural betrayal trauma theory. Transcult Psychiatry 2019;56:136346151984730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jacques-Tiura AJ, Tkatch R, Abbey A, Wegner R. Disclosure of sexual assault: Characteristics and implications for posttraumatic stress symptoms Among African American and Caucasian survivors. J Trauma Dissociation 2010;11:174–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iverson KM, Gradus JL, Resick PA, Suvak MK, Smith KF, Monson CM. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD and depression symptoms reduces risk for future intimate partner violence among interpersonal trauma survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79:193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bass JK, Annan J, McIvor Murray S, et al. Controlled trial of psychotherapy for congolese survivors of sexual violence. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2182–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. SisterSong, National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice, Center for Reproductive Rights. Reproductive injustice: Racial and gender discrimination in U.S. health care. Center for Reproductive Rights. 2014. Available at: http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/USA/INT_CERD_NGO_USA_17560_E.pdf Accessed March 21, 2021.

- 12. Holden K, McGregor B, Thandi P, et al. Toward culturally centered integrative care for addressing mental health disparities among ethnic minorities. Psychol Serv 2014;11:357–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lewis SF, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ, et al. Assault, psychiatric diagnoses, and sociodemographic variables in relation to help-seeking behavior in a national sample of women. J Trauma Stress 2005;18:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bryant-Davis T, Chung H, Tillman S. From the margins to the center: Ethnic minority women and the mental health effects of sexual assault. Trauma Viol Abuse 2009;10:330–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Long JS. Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables, vol. 7. Advanced quantitative techniques in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1997:219. [Google Scholar]

- 16. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software, Version 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17. MPLUS (Version 8.1.7). [Computer Software]. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- 18. West CM. Black women and intimate partner violence: New directions for research. J Interpers Viol 2004;19:1487–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Anyikwa VA. The intersections of race and gender in help-seeking strategies among a battered sample of low-income African American women. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 2015;25:948–959. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Graham LF. Navigating community institutions: Black transgender women's experiences in schools, the criminal justice system, and churches. Sexual Res Soc Policy 2014;11:274–287. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schulz AJ, Mullings L. Gender, race, class, and health: Intersectional approaches. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ross LJ. Reproductive justice as intersectional feminist activism. Souls 2017;19:286–314. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ross L. (2006). Understanding Reproductive Justice: Transforming the Pro-Choice Movement. Off Our Backs, 36(4), 14–19. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20838711 Accessed March 21, 2021.

- 24. Cheeseborough T, Overstreet N, Ward LM. Interpersonal sexual objectification, Jezebel stereotype endorsement, and justification of intimate partner violence toward women. Psychol Women Q 2020;44:203–216. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mullings L. Resistance and Resilience: The Sojourner syndrome and the social context of reproduction in central Harlem. Transform Anthropol 2005;13:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cho H, Shamrova D, Han J-B, Levchenko P. Patterns of intimate partner violence victimization and survivors' help-seeking. J Interpers Viol 2020;35:4558–4582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schoen J. Choice & coercion: Birth control, sterilization, and abortion in public health and welfare. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Law Students for Reproductive Justice. If you really care about preventing domestic and sexual violence, you should care about reproductive justice! National Women's Law Center. 2013. Available at: https://www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/intimate_partner_violence_repro_justice_10-25-13.pdf Accessed March 21, 2021.

- 29. SisterSong. Accountability plenary. [Conference Panel]. Let's Talk About Sex Conference, Atlanta, GA. 2019. Available at: https://www.letstalkaboutsexconference.com Accessed March 21, 2021.

- 30. Graham LF, Reyes AM, Lopez W, Gracey A, Snow RC, Padilla MB. Addressing economic devastation and built environment degradation to prevent violence: A photovoice project of detroit youth passages. Commun Literacy J 2013;8:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Washington HA. Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. New York: Doubleday Books, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sullivan HR. Hospitals' obligations to address social determinants of health. AMA J Ethics 2019;21:248–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reeve LC. How can advocates better understand Transformative Justice and its connection to gender-based violence intervention and prevention work. National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. 2020. Available at: https://vawnet.org/news/how-can-advocates-better-understand-transformative-justice-and-its-connection-gender-based Accessed March 21, 2021.

- 34. Ross L, Solinger R. Reproductive justice: An introduction, vol. 1. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]