Abstract

This study examines the influence of COVID-19 on unpaid leave, the direct impacts of psychological contract breach on organizational distrust and turnover intention, and their indirect impact through emotional exhaustion. The study used partial least squares to analyze the data set of 238 questionnaires from hospitality establishments. Results indicate a significant direct positive impact of psychological contract breach on organizational distrust and favorable indirect effects through emotional exhaustion. However, psychological contract breach had no direct effects on turnover intention. The study has equally found the positive effect of organizational distrust on turnover intention. The research provides both theoretical and practical implications and suggests areas for further studies.

Keywords: COVID-19, Unpaid leave, Psychological contract breach, Emotional exhaustion, Organizational distrust, Turnover intention, Zanzibar

1. Introduction

In the wake of COVID-19, the world has experienced a devastating and unprecedented situation that significantly impacted every angle of human life. Among the steps taken to lessen the spread of the pandemic were a lockdown and social distancing, which ultimately led to the closure of the businesses (Fernandes, 2020; Karim & Haque, 2020). The closure of firms triggered many unfavorable job conditions such as voluntary retirements, temporary suspension, reduced working hours, paid and unpaid leave (Gössling, Scott, & Hall, 2020). Among the most impacted were tourism, transport, and hospitality-related businesses (Ali & Çobanoğlu, 2020). As a result, countless people from the tourism and hospitality industry lost their jobs, and some were on either paid or unpaid leave (Foo, Chin, Tan, & Phuah, 2020). Most airlines, such as Cathay Pacific, Jetstar, Singapore Airlines, and Malaysian airline, sent their employees on unpaid leave. More than 25,000 people in Cathay pacific alone, which accounted for 75% of all employees, were advised to take unpaid leave (ILO, 2020). Apart from the airline, the hotels, tour operators, restaurant sectors were also devastated by the pandemic. In Vietnam, about 23,000 employees had to take temporary leave due to a lack of customers. In New Zealand, 340 restaurant employees had to be laid off (ILO, 2020). The unpaid leave caused some frustration which exacerbated the psychological contract breach among the employees. Literature suggests that psychological contract breach (PCB) is one of the main determinants of employee job performance and turnover intentions.

Zanzibar is no different when it comes to how COVID-19 has impacted the hospitality and tourism industry. For the past two decades, Zanzibar has experienced a remarkable increase in tourism, coupled with increased accommodation facilities and tourists' restaurants. Accordingly, the archipelago currently records 467 accommodation facilities, ranging from small lodges and guest houses to five-star hotels and resorts, 233 tour operators (RGoZ, 2020), and a good number of restaurants specifically focusing on tourists. Interestingly, Zanzibar's labor laws provide room for the employers to lay off their employees based on unpaid leave for a month, which may be extended to another three months after the employer has requested and obtained the written consent from the labor commissioner. The labor laws provide two conditions for a firm to lay off its employees. First, in the circumstance that a firm is unable to pay the employees due to financial constraints. Second, during the force majeure such as the pandemic. As such, owners of hotels, tour operators, and restaurants sent their employees on unpaid leave for several months during the pandemic, warranting an investigation into how such psychological contract breach can lead to organizational distrust, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intentions.

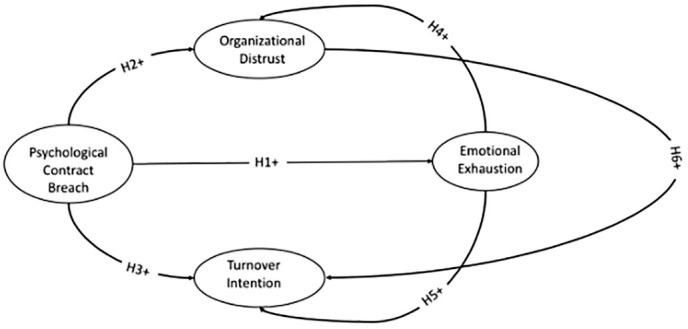

In tourism and hospitality, previous studies on psychological contract breach have focused on the PCB link with firm's identification, commitment, and work-related performance (Li, Wong, & Kim, 2016), the mediating role of the PCB in the association between individual leadership styles and intention to quit the organization (Chen & Wu, 2017), the effects of the PCB on life-related satisfactions (Ampofo, 2020), the effect of PCB on the intention to remain in work and task-related proactive behaviors and pro-environmental behaviors (Karatepe, Rezapouraghdam, & Hassannia, 2020). While these studies provide a comprehensive understanding of the psychological contract breach, research on the impact of psychological contract breach on organizational distrust and turnover intention in unpaid leave and pandemics like Covid-19 remains scarce. Against this backdrop, this research attempts to add knowledge to the understanding of the direct effects of the psychological contract breach on organizational distrust and turnover intention and its indirect impact through emotional exhaustion under the context of unpaid leave during an ongoing pandemic. This study has the following objectives:

- (1)

To examine the impact of the psychological breach on organizational distrust and turnover intention.

- (2)

To assess the mediating role of emotional exhaustion in the relationship between psychological contract breach and organizational distrust on the one hand and turnover intention on the other hand.

- (3)

To examine the effects of organizational distrust on turnover intention.

In this vein, the rest of the study highlights the literature reviews on psychological contract breach, emotional exhaustion, organization distrust, turnover intention, and hypothesis. Part three of the study is a methodology, followed by the findings, conclusion, implications, limitations, and areas for further studies.

2. Literature review

2.1. Psychological contract breach

The primary task in modern organizations is to understand their employees' attitudes and behaviors in determining psychological contract breach. The norm of reciprocity is central to the psychological contract. Both parties' (employer and employees) prospects are equally satisfied, bringing a mutual bond between the parties (Ma, Liu, Lassleben, & Ma, 2019). Organizations operate in a heightening situation of limited resources and pressure to keep competitive and sustainable (Arunachalam, 2020). It results in employees developing expectations in return for their contribution to the organization (Balabanova, Ehrnrooth, Koveshnikov, & Efendiev, 2019). When the respective organization delays giving back to employees what they either directly or explicitly promised, then the sense of psychological contract breach is activated (Arunachalam, 2020). Morrison and Robinson (1997) defined psychological contract breach as an organizational failure to meet some of the obligations which understood employment arrangement either implicitly or explicitly. In realizing the breach, different negative and inappropriate consequences can be expected, such as counterproductive work behavior, absenteeism, and even turnover intention (Shen, Schaubroeck, Zhao, & Wu, 2019), not healthy for organizations. Employees who perceive the psychological contract breach can develop depression, anxiety, perception of injustice, and emotional exhaustion.

2.2. Emotional exhaustion

Emotional exhaustion is defined by Maslach & Goldberg (1998 p.64) as “feelings of being emotionally overextended and depleted of one's emotional resources.” Working conditions, especially the psychological aspects, are critical because they can either stimulate or impede employees' comforts and destruct innovation (Koch & Adler, 2019). Organizations require to initiate a quality relationship between employees and their supervisors since they may display authentic emotions, which is essential in interacting and communicating with others while correcting interpersonal behavior (Medler-Liraz & Seger-Guttmann, 2018). In the tourism and hospitality industry, especially frontline employees are the key to the business's differentiation or competitive advantage and need to regulate their feelings and expressions for their success (Chen, Chang, & Wang, 2019). Emotional competence is an important aspect, and as such, it regulates individual responses to events (Alola, Olugbade, Avci, & Öztüren, 2019). Employees' emotions determine their attitudes towards the organization when they are emotionally exhausted; they become helpless and decrease their trust towards the organizations (Son, 2014).

2.3. Organizational distrust

Lewicki, McAllister, and Bies (1998) defined the concept of distrust as negative expectations that individuals confidently hold as regards another's conduct. Guo, Lumineau, and Lewicki (2017) argue that the conception of distrust relies on the notion of unacceptable or undesired behavior of the partner. Individuals may perceive the other partner as deceiving or misrepresenting information to gain something or any other purpose that the partner thinks is valuable (Raza-Ullah & Kostis, 2019). A working environment can cultivate distrust if it does not give the ability to do what needs to be done, technical knowledge and skills, cares and motivates, shows good faith in their agreements, fulfills employees' promises, and tells the truth (Camblor & Alcover, 2019). Consequently, distrust can yield many injurious effects; for example, distrust can reduce autonomy, lead to conflict, deception and skepticism, suspicion, or even sabotage (Lumineau, 2017). Therefore, when employees distrust the organization, they will not enjoy working with the same organization for a long-term career. Which eventually trigger their intentions to leave the organization (Shahnawaz & Goswami, 2011).

2.4. Turnover intention

The tourism and hospitality industry is considered one of the sectors that experience high employee turnover rates (Gok, Akgunduz, & Alkan, 2012). Among the factors associated with employee turnover are lack of motivation, perceived organizational support, organizational justice, and job satisfaction (Oruh et al., 2020). Employees' turnover can challenge organizational efficiency and production (Das, Byadwal, & Singh, 2017), which is very important for sustainability and building a competitive edge, especially in this era of global competition (Zahra, Khan, Imran, Aman, & Ali, 2018). Turnover intention is a precursor to employee turnover and is defined as the likelihood that individuals withdraw from the organization and likely search for alternative jobs (Haque, Fernando, & Caputi, 2019). Oruh et al. (2020) provide that employees' working environment, background, and environment are the center in facilitating turnover intention. Similarly, an unconducive working environment and the availability of better job opportunities contribute to turnover intention (Yildiz, 2018). Organizations can suffer tremendous loss in human and social capital and workflow interference (Oruh et al., 2020).

2.5. Theoretical framework and hypotheses development

2.5.1. Psychological contract breach and emotional exhaustion

The psychological contract theory can best explain employees' behavior, which is the prescription to the relationship between employee and employer (Flores, Guaderrama, Arroyo, & Gómez, 2019). Contrary to that, when employees observe that their organizations have failed to meet the perceived mutual promises, they take it as a psychological contract breach (Morrison & Robinson, 1997), leading to stress and, in due course, job strain (Gakovic & Tetrick, 2003). According to Mehrabian and Russell (1974), an individual's organism, an internal state, would reflect and respond to stimuli about a particular environment. The stimulus can be any enhancements that a firm aims to augment its employees' actions (Goi, Kalidas, & Yunus, 2018). A psychological contract breach is a good predictor of employees' emotional responses so that the breach prompts negative emotional responses (Piccoli & De Witte, 2015). Therefore, in this end, we propose.

H1

: Psychological contract breach is positively related to employee emotional exhaustion.

2.5.2. Psychological contract breach and organizational distrust

Psychological contract breach reduces the continuous reciprocal cycle and distracts individuals' commitments towards organizational goals (Cassar & Briner, 2011). The continuous reciprocal facilitated by a psychological contract whereby individuals are willing to invest much of their efforts with the organizations' anticipation would fulfill their promises (Cassar & Briner, 2011). It is well known that when employees perceive a psychological contract breach, they would respond negatively, and hence, forcing individuals to believe that their organizations lack integrity, for that reason developing negative feelings on the organizations (Sarikaya & Kok, 2017). It is argued that when employees notice the breach of the psychological contract, they first become dissatisfied, as the time-evolving they lower both organizational commitment and performance (Bunderson, 2001). As such, the psychological contract breach can trigger employees perceived organizational distrust. Hence, the following hypothesis is suggested.

H2

: Psychological contract breach is positively related to organizational distrust.

2.5.3. Psychological contract breach and turnover intention

Employee attitudes and behaviors such as turnover or turnover intentions, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors can better be predetermined by the perceived psychological contract breach (Bunderson, 2001; Robinson, 1996; Robinson & Morrison, 1995; Robinson & Rousseau, 1994). As noted earlier, the perceived breach can be due to the employers' failure to fulfilling their obligations (Robinson & Morrison, 1995). A psychological contract breach can act as a stimulus that can trigger an employee's organism, which eventually would lead to response (turnover intention) (Mehrabian & Russell, 1974). Thus, the following hypothesis is suggested.

H3

: Psychological contract breach is positively related to employees' turnover intentions.

2.5.4. The mediating role of emotional exhaustion on psychological contract breach, organizational distrust, and turnover intentions

Mutual relations in an organization are the key to organizational success. Employees respond positively when their efforts, knowledge and skills, and organizational promises are acknowledged and fulfilled. Whenever there is a lack of mutual relations in the sense that there is a breach of the psychological contract, it leads to job insecurity and emotional exhaustion (Piccoli & De Witte, 2015). It is argued that the fulfillment of organizational obligations can predict emotional exhaustion. If the organization fails to fulfill its obligations to the employees, employees become dissatisfied and become emotionally exhausted (Gakovic & Tetrick, 2003). Consistently, Shore and Tetrick (1994) posit that when organizations fail to fulfill their contractual obligations, apparently employees would develop emotional exhaustion due to stress resulting from the reduced hope and control over their expectations. In a similar vein, Gakovic and Tetrick (2003) predicted that employees would develop emotional exhaustion and decreased job satisfaction due to organizational failure to fulfill their obligations, which leads to job strain. Different researchers have agreed on the perceived psychological contract breach as the predictor of employee emotional exhaustion (Cantisano, Domínguez, & García, 2007; Chambel & Oliveira-Cruz, 2010; Jamil, Raja, & Darr, 2013). When employees perceive that their resources are being swindled, they become emotionally exhausted (Maslach, 1993). Empirically, emotional exhaustion is believed to affect turnover intentions (Alola et al., 2019; Karatepe & Kilic, 2015). Psychological contract breach leads to emotional exhaustion (Piccoli & De Witte, 2015). Eventually, emotional exhaustion leads to turnover intentions (Alola et al., 2019). On the other hand, employees lose trust in the organization when they perceive the organization failed to fulfill its obligations. Hence, psychological contract as a stimulus would activate employees' cognitive state (organism), which is, in this case, emotional exhaustion. In turn, employees would respond to losing their trust in the organization and developing turnover intentions. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses.

H4

: Emotional exhaustion will mediate the influence of psychological contract breach on organizational distrust.

H5

: Emotional exhaustion will mediate the influence of psychological contract breach on turnover intentions.

2.5.5. Organizational distrust and turnover intention

While organizational trust is considered an essential factor for the organization's success (Kim & Yang, 2017), organizational distrust is at the focus of social relationships. It is connected to a complicated and wide range of organizational issues such as transaction costs, intergroup behaviors, cognitive processes, revenge, purchasing decisions, and administrative control (Guo et al., 2017). Empirical evidence shows that distrust has a significant effect on employees' turnover intentions (Kang, Kim, & Han, 2018; Kim & Yang, 2017). The level of trust is higher to satisfied employees, while those who are not satisfied show a high level of distrust, which in due course leads to turnover intentions (Çınar, Karcıoğlu, & Aslan, 2014; Zeffane & Melhem, 2017). Therefore, we propose that.

H6

: Organizational distrust is positively related to turnover intention.

Fig. 1 depicts the conceptual framework developed for this study.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures

This study adopted all measures from previous literature. Five items of psychological contract breach were adapted from Robinson and Morrison (2000). Emotional exhaustion was measured with five items adapted from Moore (2000). Three items of turnover intention were inspired by Karatepe (2013). Moreover, thirteen organizational distrust items were adopted from Adams, Highhouse, & Zickar, 2010). All the items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree. Three experts, three from the industry and three from the academia, were consulted to assess the content validity. Some items were adjusted based on recommendations from the experts. Accordingly, as some of the employees' English level is poor in Zanzibar, a back-translation was considered (Kaya & Karatepe, 2020). As Such, the instrument was first prepared in English. Second, the English version questionnaire was given to an independent translator fluent in English and Swahili. Third, Swahili's translated questionnaire was given again to another expert influent in Swahili and English to translate it back to English. As two of the present study authors are native Swahili speakers who are also very conversant in English, we finally assess the two English versions if they explain the same thing logically. There were screening questions aimed at identifying employees from the hospitality industry and only those who are on unpaid leave. A pilot study with 30 employees was eventually conducted. The instrument reliability was tested through the Cronbach alpha coefficient, which was then found to be above the minimum threshold of >0.70. Appendix – A includes a copy of the questionnaire used to collect data.

3.2. Data collection

A cross-sectional study was conducted to collect data from the employees of four- and five-stars hotels, seaside restaurants, and tour operators in Zanzibar. The study utilized snowball and purposive sampling to acquire the respondents. Respondents were ensured of their anonymity and the volunteer nature of their participation in the research. A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed, out of which 238 questionnaires were deemed fit for further analysis after removing missing values and unengaged responses. This sample size fulfills the required sample size's necessary condition (Ali, Ciftci, Nanu, Cobanoglu, & Ryu, 2021). The demographic characteristics showed that 58.9% of respondents were male. In comparison, 41.1% of respondents were females, 41% were between the age group of 28–37 years old, 76.9% had secondary and high school education, and 44.1% had a work experience of 1–5 years 48.3% of respondents were married.

4. Data analysis and results

4.1. Common method variance

Several precautions based on the procedural and statistical remedies proposed by (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003) were considered to mitigate common method bias. First, respondents were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of the study. Secondly, the instrument used psychological and methodological separation by concealing the study's purpose and using different scales. There were also reverse items in the questionnaire to assess the respondents' concentration. Indeed, as the study did not use the time separation, Harman's single factor tests were conducted to assess the presence of method bias in the sample. The study found less than 40% of the variance explained in the single factor, which confirmed that our study does not suffer from common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Moreover, all the correlations among all the constructs are less than 0.9. These statistical tests portray that common method bias was not likely to have affected this study significantly.

4.2. Measurement model assessment

SmartPLS 3.0 was used as a statistical tool to conduct Partial Least Square (PLS) based SEM to test the study's framework and hypotheses. PLS-SEM works ideally under non-normality conditions and smaller sample sizes (Ali, Rasoolimanesh, Sarstedt, Ringle, & Ryu, 2018). The study tested the normality evaluation by using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The results showed that the data was not normally distributed by having an error level of 5%. Therefore, PLS-SEM was used. The measurement model for convergent validity was assessed through loadings, AVE, CR, CA, and rho-A. As shown in Table 1 , except for one item, all the loadings are exceeding 0.6, which is the recommended value. The values of CR, CA, and rho-A are exceeding their recommended values of 0.7, and the values of AVE are also greater than 0.5 (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015; Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2017).

Table 1.

Measurement model assessment.

| Constructs | Items | Loadings | AVE | CR | rho-A | CA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My employer has broken all the promises made during recruitment. | 0.835 | 0.594 | 0.879 | 0.833 | 0.827 | |

| I feel that my employer had not fulfilled the promises made to me when I was hired. | 0.817 | |||||

| Psychological Contract Breach | So far, my employer has not done anything to fulfill its promises to me. | 0.706 | ||||

| I have not received everything promised to me in exchange for my contributions. | 0.735 | |||||

| My employer has broken many of its promises to me even though I have upheld my side of the deal. | 0.752 | |||||

| I fell emotionally drained from my work. | 0.723 | 0.536 | 0.852 | 0.799 | 0.788 | |

| I feel used up at the end of the work. | 0.661 | |||||

| Emotional Exhaustion | I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning and have to face another day at the job. | 0.776 | ||||

| Working all day is really a strain for me | 0.765 | |||||

| I feel burned out from my work. | 0.729 | |||||

| Our company is not respectful of laws. | 0.697 | 0.512 | 0.931 | 0.923 | 0.920 | |

| Our company is not accepting accountability for its actions. | 0.740 | |||||

| People who run our company will lie if doing so will increase company profits. | 0.710 | |||||

| Our company does not care about acting ethically. | 0.724 | |||||

| Our company will break laws if they can make more money from it. | 0.738 | |||||

| Organizational Distrust | Our company put their interests above the public's interests. | 0.733 | ||||

| Our company is driven by greed. | 0.785 | |||||

| Our company cares only about money. | 0.718 | |||||

| Our company wants power at any cost. | 0.581 | |||||

| Our company takes a lot more than they give. | 0.665 | |||||

| Our company intentionally deceives the public. | 0.725 | |||||

| Our company does not consider the needs of its employees when making business decisions. | 0.717 | |||||

| Our company exploits its workers. | 0.749 | |||||

| Likely, I will actively look for a new job next year. | 0.799 | 0.717 | 0.884 | 0.802 | 0.801 | |

| Turnover Intention | I often think about quitting. | 0.869 | ||||

| I will probably quit this job next year. | 0.870 |

Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations was used to test the discriminant validity of the constructs (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015). The HTMT criterion for assessing discriminant validity is considered a better and more conservative test. Table 2 shows the results of the discriminant validity. Based on the Table, all the HTMT criterion values are less than 0.85 as per Kline's (2015) recommendations.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity.

| Emotional exhaustion | Organizational distrust | Psychological contract breach | Turnover intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion | ||||

| Organizational Distrust | 0.605 | |||

| Psychological Contract Breach | 0.556 | 0.809 | ||

| Turnover Intention | 0.600 | 0.778 | 0.605 |

4.3. Structural model assessment

The hypothetical relationships were also assessed using Smart PLS 3.0. Table 3 shows the results of direct effects. In terms of significance, psychological contract breach was statistically significant and positive in its effect on emotional exhaustion and organizational distrust (p < 0.01, β = 0.467; p < 0.01, β = 0.580). Thus, H1 and H2 were supported. Organizational distrust also had a significant positive effect on turnover intention (p < 0.01, β = 0.560), showing H6 was also supported. However, H3 was not supported by showing that psychological contract breach does not affect turnover intention (p > 0.05, β = 0.009). Next, the results of R2 showed that psychological contract breach, emotional exhaustion, and organizational distrust explain 47.8% variance in turnover intention (R2 = 0.478), psychological contract breach and emotional exhaustion explain 56.0% variance in organizational distrust (R2 = 0.560), whereas psychological contract breach explains 21.8% variance in emotional exhaustion (R2 = 0.218). As per Cohen's (1988) guidelines, the R2 values of turnover intention and organizational distrust show substantial variance, and emotional exhaustion shows moderate variance.

Table 3.

Structural model results (direct relationships).

| No | Hypotheses | p-value | Β | f2 | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Psychological Contract Breach - > Emotional Exhaustion | 0.000 | 0.467 | 0.280 | Supported |

| H2 | Psychological Contract Breach - > Organizational Distrust | 0.000 | 0.580 | 0.597 | Supported |

| H3 | Psychological Contract Breach - > Turnover Intention | 0.910 | 0.009 | 0.000 | Not Supported |

| H6 | Organizational Distrust - > Turnover Intention | 0.000 | 0.560 | 0.264 | Supported |

We have also assessed model fit using standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) and the RMStheta measures (Henseler, Hubona, & Ray, 2016). The score of SRMR (RMStheta) was 0.06 (0.11), which confirmed an adequate fit for PLS path models as it was less than the recommended score of 0.08 (0.12). Next, using Cohen f2, this study has also assessed the effect of the predictor latent variables. As per Cohen's (1988) guidelines, the f2 value of 0.2 shows a small effect size, 0.15 shows a medium effect size, and 0.35 shows a large effect size. As shown in Table 4 , H1 and H6 have medium effects, H2 has a large effect, and H3 does not affect.

Table 4.

Results of mediation effects.

| DVs = Organizational distrust (OD), turnover intention (TI) | Independent variable (IV) |

|---|---|

| M = Emotional exhaustion (EE) | Psychological contract breach (PCB) |

| PCB -_ > OD | 0.708***(sig.0.000) |

| PCB -_ > TI without EE | 0.496***(sig.0.000) |

| PCB -_ > EE -_ > OD | 0.128***(sig.0.000) |

| PCB -_ > EE -_ > TI | 0.487***(sig.0.000) |

| PCB -_ > EE-_ > OD (Indirect effect) | 0.128***(sig.0.000) |

| PCB -_ > EE-_ > TI (Indirect effect) | 0.090***(sig.0.009) |

| PCB -_ > EE | 0.467***(sig.0.000) |

| EE -_ > OD | 0.274***(sig.0.000) |

| EE -_ > TI | 0.193***(sig.0.005) |

| Mediation Path | (H4) PCB— > EE — > OD |

| (H5) PCB — > EE — > TI | |

| Mediation Effect | (H4) Yes |

| (H5) Yes | |

| Degree of Mediation | (H4) Partial |

| (H5) Partial | |

| Hypotheses Results | (H4) Supported. |

| (H5) Supported |

4.4. Mediation analysis

Mediation analysis was used to determine the mediation effect of emotional exhaustion between the relationship of psychological contract breach and organizational distrust and psychological contract breach and turnover intention. The results of the mediation analysis are reported in Table 4. Based on the Table, both H4 and H5 were supported, showing that emotional exhaustion partially mediates the relationship between psychological contract breach and organizational distrust and psychological contract breach and turnover intention.

5. Discussion and conclusion

This study aimed to examine the influence of unpaid leave during COVID-19 through the direct effect of psychological contract breach on organizational distrust and turnover intention and their indirect impact through emotional exhaustion. By doing so, we made six hypotheses. The H1 and H2 were supported and indicated that psychological contract breach is positively related to emotional exhaustion and organizational distrust. The findings revealed that due to the unpaid leave during COVID-19, the psychological contract breach increased employees' emotional exhaustion and increased their distrust towards organizations in the hospitality industry. The findings are consistent with the previous studies (Costa & Neves, 2017; Piccoli & De Witte, 2015), showing that psychological contract breach prompts negative emotional responses and increases organizational distrust. The findings also supported H3 and showed that organizational distrust is positively related to turnover intention. It demonstrated that organizational distrust is a significant predictor of turnover intention under the circumstances of unpaid leave. Such relationships were consistent with previous literature on organizational distrust and turnover intention (Kang et al., 2018; Kim & Yang, 2017; Sarikaya & Kok, 2017).

Unpredictably, the results showed that psychological contract breach had no significant effect on turnover intention. Interestingly, our findings contradict previous studies (Bunderson, 2001; Chen & Wu, 2017). It can be due to the following reasons. First, most of the hotels, beach resorts, and restaurants in Zanzibar have mobilized a significant number of their staff and trainees to reduce their payroll expenses (Mugassa, 2014). The hospitality and tourism industry in Zanzibar lacks job insecurity and sound human resource practices (Darvishmotevali & Ali, 2020; Mugassa, 2014; ZATI, 2008). Such conditions may have already decreased employees' expectations towards their employer's behavior fulfilling the obligations. It implies that employees are already high lower levels of commitment towards such organizations due to their failure in meeting their obligations towards employees (psychological contract breach). As such, unpaid leave may not be a significant concern for these employees. Second, Zanzibar depends heavily on tourism, and all other economic sectors are not relatively healthy, implying a shortage of job opportunities in other sectors. In the current situation in COVID-19, employees do not have too many options to secure other jobs. So even if one decides to leave, there is no possibility of getting another job elsewhere.

The data also showed that emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between psychological contract breach and organizational distrust and the relationship between psychological contract breach and turnover intention. The findings are consistent with Gakovic and Tetrick (2003) and Alola et al. (2019) by showing that employees in the hospitality and tourism industry experience emotional exhaustion due to psychological contract breach, which as a result exhibits organizational distrust and high levels of turnover intention. Our findings have also shown an essential insight that employees with unpaid leave will be emotionally exhausted and blame their organizations, start distrusting them, and intend to leave them even under worldwide pandemics or natural disasters.

5.1. Theoretical and practical implications

This study's findings contribute to the hospitality, tourism, and human resource management literature in multiple ways. First, this study developed and tested a model with the relationship between psychological contract breach and emotional exhaustion and how emotional exhaustion mediates the relationships between psychological contract breach, organizational distrust, and turnover intention. This study also contributes to the literature on psychological contract breach by showing that psychological contract breach caused by some crisis can change the level of emotional exhaustion, leading to organizational distrust and turnover intention. The present study proposes some vital descriptions for the psychological contract breach-emotional exhaustion relationship. It also approves the mediating role of emotional exhaustion connecting psychological contract breach to organizational distrust and turnover intention. Organizational distrust due to psychological contract breach may show that the employees expected that the management makes better decisions to protect the employees and react better. Guo et al. (2017) proved that managerial decision-making could cause organizational distrust. In 2011 in Egypt, most of the tourism industry workers during the political crisis had high turnover intentions to leave the organization. They lost their faith in their organization because their unstable conditions did not know how to work (Elshaer & Saad, 2017). It shows that unpaid leave during a time of crisis can lead the employees to leave the job. Thus, the study pointed out that the knowledge of crisis management and the managers' competencies in unpredictable and uncertain situations can be crucial to keep the employees motivated for the job.

The data for this study was collected from the employees of the hospitality and tourism industry in Zanzibar. Archaeology has gained its room as a holiday destination for tourists. The hotel industry of Zanzibar is considered to be the most significant part of its tourism industry (Mkama, 2015). Thus, the empirical evidence from the hospitality and tourism industry of Zanzibar contributes to the employees' work-related outcomes and psychological contract breach. Also, the results revealed that even if the pandemics are not in control of the organizations, it still does not change employees' perceptions towards their organizations in Zanzibar when they are on unpaid leave. Besides, an insignificant relationship between psychological contract breach and turnover intention among the hospitality and tourism industry employees with unpaid leave during COVID-19 in Zanzibar established a new concept. It demonstrated that although the level of psychological contract breach is high during the crisis, employees are aware of the difficulty in finding new jobs during COVID-19 (Van Hootegem, De Witte, De Cuyper, & Elst, 2019) in Zanzibar. A study on the labor market showed that the job selection opportunities during the crisis were minimal, and therefore, leaving the organization to deal with psychological contract breach may not be the best way (Kim, Kim, & Yoo, 2012; Snorradóttir, Vilhjálmsson, Rafnsdóttir, & Tómasson, 2013). It also raises a concern as if more investment comes to Zanzibar. Employees can shift their jobs. Therefore, the employers of hospitality and tourism organizations in Zanzibar, even when the economy recovers, should respect the employees' efforts invested in the job, create more challenging tasks, and support them to increase their desire to stay. In this way, this study's findings may apply to other African nations and small islands' tourism destinations trying to develop the hospitality and tourism industry as the primary revenue source.

This study also offers some practical implications for the management of the hospitality and tourism industries in Zanzibar. As for this study, the data was collected during the pandemic. The findings have significant implications for the tourism and hospitality industry managers in Zanzibar as they can understand the potential changes better in employees' attitudes when they resume their work. Also, in determining psychological outcomes in specific work situations, the psychological contract breach becomes primarily essential. However, in Zanzibar, only life difficulties and lack of alternatives have retained the employees in the hospitality and tourism industry. Thus, in general, these organizations, especially during periods of crisis, need to be careful about their promise. For instance, if the conditions are out of control for the managers, even if they want to fulfill the promises about the psychological contract, they may not fulfill in the future. Therefore, organizations to reduce negative relationships and perceptions of psychological contract breach may increase communication between employees and employers. They should send them emails or messages on a daily or weekly basis, as transparent and open communication programs lessen uncertainty about job loss. If they cannot pay salary to their employees during the crisis, they may initiate different financial support programs such as free food packages, grocery items, free medication. They should also focus more on government aid, as most of these private hotels, restaurants, and tour operators have already collapsed due to a lack of customers.

Although global crises and pandemics are not in the organizations' control, the organizations in Zanzibar can still take some actions and initiate programs to reduce adverse outcomes. The organizations in Zanzibar should add crisis management programs and allocate a budget for them so that they will be able to pay their employees in case of any emergency or during the crisis. Also, the management should research to gather information from the employees on under what similar conditions and factors they become emotionally exhausted and display distrust towards organization and turnover intention. Such research will increase the understanding of different causes of turnover intention in the hospitality and tourism industry. As the hospitality and tourism industry of Zanzibar lacks contemporary human resource practices, the management should develop appropriate strategies in order to minimize employees' psychological contract breaches. Constant training and supportive mechanism programs should be developed to manage the employees with high psychological contract breach and reduce its outcome (Hur, Moon, & Jun, 2016). Finally, the findings of this study bring some implications for the government and policymakers. Indeed, due to the collapse of many entities during the pandemic, it would be advisable for the government of Zanzibar to set aside special funds to save the situation when similar events occur. The government may equally pay all employees who contributed to the social security fund at least some amount of their contribution to assist the survival of employees laid off at times of crisis.

5.2. Limitations and future suggestions

This study offers several limitations and future suggestions. First, this study has gathered data from the employees in the hospitality and tourism industry of Zanzibar. Future studies for more generalized results about the causality can collect data from other service industries, including banks, hospitals, universities, and airlines. Second, the results of this study are based on cross-sectional data. Though employing previous empirical research and theory, we have tried to explain the process of mediation, yet it limits the causal interpretation. Future studies by using longitudinal data will make more clear conclusions about the causality among the variables. Other designs, such as time-lag, will also minimize the risk of potential bias. Third, while the findings of this study are not deprived of limitations, we believe future studies in addition to emotional exhaustion can also test organizational distrust and job insecurity as mediators between psychological contract breach and turnover intention to validate these results. Last, this study has collected data from employees with unpaid leave during COVID-19. Further studies can test the model during other crises and tragedies from the employees with unpaid leave to see the differences between the results.

Contributions

- •

Moh'd Juma Abdalla: Writing- Original draft preparation; Writing - Reviewing and Editing; Data curation; Investigation.

- •

Hamad Said: Writing- Original draft preparation; Writing - Reviewing and Editing; Methodology; Investigation.

- •

Laiba Ali: Writing- Original draft preparation; Writing - Reviewing and Editing; Software; Data curation; Visualization; Formal Analysis.

- •

Faizan Ali: Writing- Original draft preparation; Writing - Reviewing and Editing; Conceptualization; Supervision.

- •

Xianglan Chen: Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Biographies

Moh'd Juma Abdalla is a PhD student in the Faculty of Tourism at Eastern Mediterranean University (Gazimagusa, TRNC, via Mersin 10, 99,628, TURKEY). His current research interests rely on Tourism, Tourism informal economy, Tour operation, Service quality, performance measurements and research methods.

Hamad Said is a PhD Candidate in the Faculty of Business and Economics, Eastern Mediterranean University. His current research interests include Mindfulness, Tourism, Service Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

Laiba Ali is a PhD student in the Faculty of Tourism at Eastern Mediterranean University. Her current research interests rely on consumer behavior, service marketing, and technology in hospitality and tourism and research methods.

Faizan Ali (PhD) is an Assistant Professor at University of South Florida. His current research interests rely on human behavior in service industries and research methods.

Xianglan Chen (Ph.D.) is a full professor in the Center for Cognitive Science of Language, Beijing Language and Culture University, Beijing, China. Her research interests include human cognition in services industries.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100854.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Questionnaire

References

- Adams J.E., Highhouse S., Zickar M.J. Understanding general distrust of corporations. Corporate Reputation Review. 2010;13(1):38–51. doi: 10.1057/crr.2010.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali F., Ciftci O., Nanu L., Cobanoglu C., Ryu K. Response rates in hospitality research: An overview of current practice and suggestions for future research. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly. 2021;62(1):105–120. doi: 10.1177/1938965520943094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali F., Çobanoğlu C. 2020. Global tourism industry may shrink by more than 50% due to the pandemic. (The conversation) [Google Scholar]

- Ali F., Rasoolimanesh S.M., Sarstedt M., Ringle C.M., Ryu K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2018;30(1):514–538. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-10-2016-0568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alola U.V., Olugbade O.A., Avci T., Öztüren A. Customer incivility and employees’ outcomes in the hotel: Testing the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tourism Management Perspectives. 2019;29(July):9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ampofo E.T. Do job satisfaction and work engagement mediate the effects of psychological contract breach and abusive supervision on hotel employees’ life satisfaction? Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management. 2020;00(00):1–23. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2020.1817222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam T. The interplay of psychological contract breach, stress, and job outcomes during organizational restructuring. Industrial and Commercial Training, March. 2020 doi: 10.1108/ICT-03-2020-0026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanova E., Ehrnrooth M., Koveshnikov A., Efendiev A. Employee exit and constructive voice as behavioral responses to psychological contract breach in Finland and Russia: A within- and between-culture examination. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2019:1–32. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019.1699144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bunderson J.S. How work ideologies shape the psychological contracts of professional employees: Doctors’ responses to perceived breach. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2001;22(7):717–741. doi: 10.1002/job.112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camblor M.P., Alcover C.M. Integrating distrust antecedents and consequences in organizational life. Revista de Psicologia Del Trabajo y de Las Organizaciones. 2019;35(1):17–26. doi: 10.5093/jwop2019a3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cantisano G.T., Domínguez J.F.M., García J.L.C. Social comparison and perceived breach of psychological contract: Their effects on burnout in a multigroup analysis. Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2007;10(1):122–130. doi: 10.1017/S1138741600006387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassar V., Briner R.B. The relationship between psychological contract breach and organizational commitment: Exchange imbalance as a moderator of the mediating role of violation. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2011;78(2):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambel M.J., Oliveira-Cruz F. Breach of psychological contract and the development of burnout and engagement: A longitudinal study among soldiers on a peacekeeping mission. Military Psychology. 2010;22(2):110–127. doi: 10.1080/08995601003638934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.Y., Chang C.W., Wang C.H. Frontline employees’ passion and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of emotional labor strategies. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2019;76(April):163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.-J., Wu C.-M. Improving the turnover intention of tourist hotel employees: Transformational leadership, leader-member exchange, and psychological contract breach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2017;29(7):1914–1936. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-09-2015-0490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Çınar O., Karcıoğlu F., Aslan İ. The relationships among organizational cynicism, job insecurity and turnover intention: A survey study in Erzurum/Turkey. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014;150:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the Behavioural science (2nd edition) (In Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences) [Google Scholar]

- Costa S.P., Neves P. Forgiving is good for health and performance: How forgiveness helps individuals cope with the psychological contract breach. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2017;100:124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darvishmotevali M., Ali F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2020;87:102462. [Google Scholar]

- Das P., Byadwal V., Singh T. Employee engagement, cognitive flexibility, and pay satisfaction as potential determinants of Employees’ turnover intentions: An overview. Indian Journal of Human Relations. 2017;51(July):147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra K., Henseler J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly. 2015;39(2):297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaer I.A., Saad S.K. Political instability and tourism in Egypt: Exploring survivors’ attitudes after downsizing. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events. 2017;9(1):3–22. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2016.1233109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes N. Economic effects of coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) on the world economy nuno fernandes full professor of finance IESE business school Spain. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020:29. ISSN 1556–5068, Elsevier BV. [Google Scholar]

- Flores G.R., Guaderrama A.I.M., Arroyo J.C., Gómez J.A.H. Psychological contract, exhaustion, and cynicism of the employee: Its effect on operational staff turnover in the northern Mexican border. Contaduria y Administracion. 2019;64(2):1–19. doi: 10.22201/fca.24488410e.2018.1133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foo L.P., Chin M.Y., Tan K.L., Phuah K.T. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism industry in Malaysia. Current Issues in Tourism. 2020 doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1777951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gakovic A., Tetrick L.E. Psychological contract breach as a source of strain for employees. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2003;18(2):235–246. doi: 10.1023/A:1027301232116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goi M.T., Kalidas V., Yunus N. Mediating roles of emotion and experience in the stimulus-organism-response framework in higher education institutions. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. 2018;28(1):90–112. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2018.1425231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gok O.A., Akgunduz Y., Alkan C. The effects of job stress and perceived organizational support on turnover intentions of hotel employees Ozge. Journal of Tourismology. 2012;3(2):23–32. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2020;9582:1–20. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S.-L., Lumineau F., Lewicki R.J. Revisiting the foundations of organizational distrust. Foundations and Trends® in Management. 2017;1(1):1–88. doi: 10.1561/3400000001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Hult G.T.M., Ringle C., Sarstedt M. Sage Publications; 2017. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) [Google Scholar]

- Haque A., Fernando M., Caputi P. The relationship between responsible leadership and Organisational commitment and the mediating effect of employee turnover intentions: An empirical study with Australian employees. Journal of Business Ethics. 2019;156(3):759–774. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3575-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J., Hubona G., Ray P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management and Data Systems. 2016;116(1):2–20. doi: 10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2015;43(1):115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hur W.M., Moon T., Jun J.K. The effect of workplace incivility on service employee creativity: The mediating role of emotional exhaustion and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Services Marketing. 2016;30(3):302–315. doi: 10.1108/JSM-10-2014-0342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ILO . International Labour Organization (ILO); 2020. COVID-19 and employment in the tourism sector: Impact and response in Asia and the Pacific. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil A., Raja U., Darr W. Psychological contract types as moderator in the breach-violation and violation-burnout relationships. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. 2013;147(5):491–515. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2012.717552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H.Y., Kim S., Han K. The relationship among workplace bullying, organizational commitment and turnover intention of the nurses working in public. Journal of Korean Clinical Nursing Research. 2018;24(2):178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M. High-performance work practices, work social support and their effects on job embeddedness and turnover intentions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2013;25(6):903–921. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-06-2012-0097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M., Kilic H. Does manager support reduce the effect of work-family conflict on emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions? Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism. 2015;14(3):267–289. doi: 10.1080/15332845.2015.1002069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M., Rezapouraghdam H., Hassannia R. Does employee engagement mediate the influence of psychological contract breach on pro-environmental behaviors and intent to remain with the organization in the hotel industry? Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management. 2020;00(00):1–28. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2020.1812142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karim W., Haque A. The movement control order (MCO) for COVID-19 crisis and its impact on tourism and hospitality sector in Malaysia. International Tourism and Hospitality Journal. 2020;3(2):1–7. doi: 10.37227/ithj-2020-02-09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya B., Karatepe O.M. Attitudinal and behavioral outcomes of work-life balance among hotel employees: The mediating role of psychological contract breach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 2020;42(April 2019):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.-K., Yang H.-S. The effect of organizational justice and psychological contract on turnover intention as mediated by trust and distrust. Journal of Digital Convergence. 2017:115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.G., Kim S., Yoo J.L. Travel agency employees’ career commitment and turnover intention during the recent global economic crisis. Service Industries Journal. 2012;32(8):1247–1264. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2010.545393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. Guilford Publications; 2015. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Koch A.K., Adler M. Emotional exhaustion and innovation in the workplace—A longitudinal study. Industrial Health. 2019;56(6):524–538. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2017-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki R.J., McAllister D.J., Bies R.I. Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. Academy of Management Review. 1998;23(3):438–458. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1998.926620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.J., Wong I.K.A., Kim W.G. Effects of psychological contract breach on attitudes and performance: The moderating role of competitive climate. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2016;55:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lumineau F. How contracts influence trust and distrust. Journal of Management. 2017;43(5):1553–1577. doi: 10.1177/0149206314556656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B., Liu S., Lassleben H., Ma G. The relationships between job insecurity, psychological contract breach, and counterproductive workplace behavior: Does employment status matter? Personnel Review. 2019;48(2):595–610. doi: 10.1108/PR-04-2018-0138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C. Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research. Taylor & Francis; 1993. Burnout: A multidimensional perspective; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Goldberg J. Prevention of burnout: New perspectives. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 1998;7(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80022-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medler-Liraz H., Seger-Guttmann T. Authentic emotional displays, leader-member exchange, and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies. 2018;25(1):76–84. doi: 10.1177/1548051817725266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian A., Russell J.A. An approach to environmental psychology. The MIT Press; 1974. An approach to environmental psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Mkama L.J. 2015. Assessing the role of motivation on employees performance in hotel industry in Zanzibar; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Moore J.E. Why is this happening? A causal attribution approach to work exhaustion consequences Author (s): Jo Ellen Moore Source: The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Apr., 2000), pp. 335–349 Published by: Academy of Management Stable URL. The Academy of Management Review. 2000;25(2):335–349. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison E.W., Robinson S.L. When employees feel betrayed a model of how psychological contract violation develops.Pdf. The Academy of Management Review. 1997;22(1):226–256. [Google Scholar]

- Mugassa P.M. Standards for sustainable hospitality services in Zanzibar. Tourism Educators of Association of Malaysia. 2014;11(1):55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Oruh E.S., Mordi C., Ajonbadi A., Mojeed-Sanni B., Nwagbara U., Rahman M. Investigating the relationship between managerialist employment relations and employee turnover intention: The case of Nigeria. Employee Relations. 2020;42(1):52–74. doi: 10.1108/ER-08-2018-0226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piccoli B., De Witte H. Job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: Testing psychological contract breach versus distributive injustice as indicators of lack of reciprocity. Work and Stress. 2015;29(3):246–263. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2015.1075624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., MacKenzie S.B., Lee J.Y., Podsakoff N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza-Ullah T., Kostis A. Do trust and distrust in coopetition matter to performance? European Management Journal. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2019.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- RGoZ . 2020. Zanzibar hotels and tour operators list_ 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S.L. Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1996;41(4):574–599. doi: 10.2307/2393868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S.L., Morrison E.W. Psychological contracts and OCB: The effect of unfulfilled obligations on civic virtue behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1995;16(3):289–298. doi: 10.1002/job.4030160309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S.L., Morrison E.W. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 21, 5. 2000. The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study; pp. 525–546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S.L., Rousseau D.M. Changing obligations and the psychological contract a longitudinal study. Academy of Management Journal. 1994;37(1):137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sarikaya M., Kok S.B. The relationship between psychological contract breach and organizational cynicism. 2017. Proceedings 6th Eurasian multidisciplinary forum, EMF 2017 27-28; pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shahnawaz M.G., Goswami K. Effect of psychological contract violation on organizational commitment, trust and turnover intention in private and public sector Indian organizations. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective. 2011;15(3):209–217. doi: 10.1177/097226291101500301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Schaubroeck J.M., Zhao L., Wu L. Workgroup climate and behavioral responses to psychological contract breach. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10(FEB):1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore L.M., Tetrick L.E. Trends in organizational behavior. 1994. The psychological contract as an explanatory frame; pp. 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Snorradóttir Á., Vilhjálmsson R., Rafnsdóttir G.L., Tómasson K. Financial crisis and collapsed banks: Psychological distress and work-related factors among surviving employees-a nation-wide study. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2013;56(9):1095–1106. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son S.Y. The effects of perceived organizational support and abusive supervision on employee’s turnover intentions: The mediating roles of psychological contract and emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering. 2014;8(4):1081–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hootegem A., De Witte H., De Cuyper N., Elst T.V. Job insecurity and the willingness to undertake training: The moderating role of perceived employability. Journal of Career Development. 2019;46(4):395–409. doi: 10.1177/0894845318763893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz S.M. An empirical analysis of the leader-member exchange and employee turnover intentions mediated by mobbing: Evidence from sport organizations. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja. 2018;31(1):480–497. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2018.1432374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zahra S.S., Khan M.I., Imran M., Aman Q., Ali R. The relationship between job stress and turnover intentions in the pesticide sector of Pakistan: An employee behavior perspective. Management Issues in Healthcare System. 2018;4(1):1–12. doi: 10.33844/mihs.2018.60369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ZATI Zanzibar Tourism Industry growth strategic plan: A study on tourism in Zanzibar for Zanzibar association of tourism investors by Acorn consulting partnership Ltd. 2008. https://acorntourism.co.uk/projects/tourism-industry-strategic-plan-for-zanzibar-p674191

- Zeffane R., Melhem S.J.B. Trust, job satisfaction, perceived organizational performance and turnover intention: A public-private sector comparison in the United Arab Emirates. Employee Relations. 2017;39(7):1148–1167. doi: 10.1108/ER-06-2017-0135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Questionnaire