Abstract

When 2020 began, we had no idea what was to unfold globally as we learnt about the Novel-Coronavirus in Wuhan, in the Hubei province of China. As this virus spread rapidly, it became a matter of time before many countries began to implement measures to try and contain the spread of the disease. COVID-19 as it is referred to, resulted in two main approaches to fighting the viral pandemic, either through a progressive set of measures to slow down the number of identified cases designed to ‘flatten the curve’ over time (anticipated to be at least six months), or to attack it by the severest of measures including a total lock-down and/or herding exposure to fast track ‘immunisation’ while we await a vaccine. The paper reports the findings from the first phase of an ongoing survey designed to identify the changing patterns in travel activity of Australian residents as a result of the stage 2 restrictions imposed by the Australian government. The main restrictions, in addition to social distancing of at least 1.5 m, are closure of entry to Australia (except residents returning), and closure of non-essential venues such as night clubs, restaurants, mass attendee sporting events, churches, weddings, and all social gatherings in any circumstance. With some employers encouraging working from home and others requiring it, in addition to job losses, and many children attending school online from home, the implications on travel activity is extreme. We identify the initial impacts associated with the first month of stricter social distancing measures introduced in Australia.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Travel activity, Working, Working from home, Air travel, Shopping, Attitudes, Survey, Australia

Highlights

- •

General support for the actions of government and business.

- •

Widespread suppression of travel demand for all trip purposes across all modes.

- •

Sizeable shift to working from home by those who can.

- •

Public transport will face the largest hurdles in regaining confidence.

- •

Retail and food logistics will need to examine distribution processes

- •

The aviation sector will likely need to restart with a heavy focus on domestic travel.

- •

Public transport will need to take overt measures to restore confidence.

- •

The dominance of the car is further enforced in the context of biosecurity concerns.

- •

Active transport is a viable option for short inner-city trips.

- •

Infrastructure investment should be carefully considered.

- •

Flexible working arrangements are perhaps the biggest policy lever available to governments.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has created disruption to travel and activities unlike anything seen since perhaps the Second World War. The first outbreak occurring in late 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of the Hubei Province in China, quickly spread to become a global pandemic. While China was emerging from their peak of the curve in mid to late March, the rest of the world was starting to feel the exponential growth of infection and the resulting pressure on public health systems, and countries like Italy and the United States of America (particularly New York City) experienced devastating loss of life.

In the early half of March, discussion in many countries focused on the most effective forms of intervention to slow the spread of COVID-19 while grappling with the consequence of many measures to respective economies, civil liberties and social impacts that such measures would have. However, by March 31st there were over three-quarter of a million reported COVID-19 cases (754,933) and 36,522 deaths,1 by this time governments had no choice but to act.

1.1. Outlining the Australian response

Some countries like the United Kingdom initially opted for a herd immunity approach, while others such as New Zealand opted for a full-scale shutdown of social and economic activity. Australia approached COVID-19 in a systematic way. A key component of the response was the formation of the National Cabinet on the 13th of March, an intergovernmental (state and federal) committee to coordinate and deliver a consistent national response to COVID-19. A key report to the National Cabinet is the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee, chaired by the National Chief Medical Officer and includes state and territory chief health officers. Business and labour union representations were also made to Cabinet.

The purpose of the cabinet was to ensure uniform risk management and timeliness of response, along with clarity and coherence in jurisdictional responses. National Cabinet developed uniform policy responses, with each state jurisdiction left to determine how to implement the policy in their own context. While some discrepancies in implementation existed, such as New South Wales keeping schools open longer than other states and maintain open state, through to marginally tougher social distancing policies in Victoria, the response to COVID-19 across Australia was in the main, uniform.

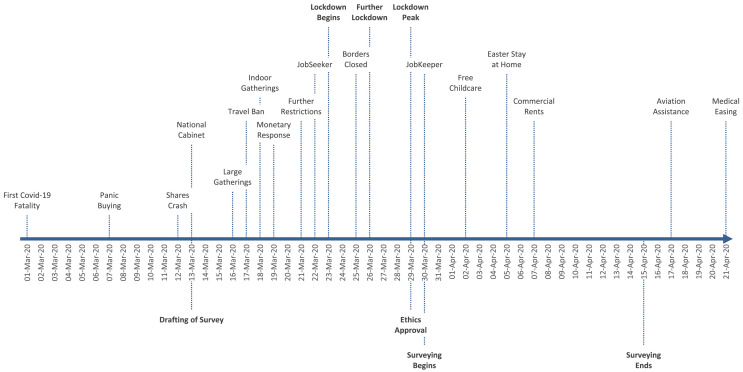

In quick succession, National Cabinet made a number of announcements pertaining to increasing restrictions and assistance measures in light of those restrictions. Fig. 1 provides a timeline overviewing the key developments in the response to COVID-19, along with milestones in the development of the survey and collection of data. Table 1 gives more details about each of these milestones. Importantly, it was the 29th of March when restrictions in Australia reached highest point. At this time public gatherings were limited to no more than two people, those with chronic illness or over the age of 70 urged to stay home and the outlining of only four acceptable reasons for Australians to leave their houses: shopping for essentials; for medical or compassionate needs; exercise in compliance with the public gathering restriction of two people; and for work or education purposes. Violation of the restrictions carried fines of $1000 per person and $5000 per business.2

Fig. 1.

Key events in the initial stages of COVID-19.

Table 1.

Detailing key events in initial stages of COVID-19.

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Mar-20 | First Covid-19 Fatality | Perth man from Diamond Princess cruise ship passes away. |

| 7-Mar-20 | Panic Buying | Supermarket panic buying starts gaining attention in media. |

| 12-Mar-20 | Shares Crash | Global stock market records largest fall since 1987. |

| 13-Mar-20 | National Cabinet | Federal and State leaders unite. $17.6b assistance package announced. |

| 16-Mar-20 | Large Gatherings | Gatherings of > 500 banned. People arriving in Australia must self-isolate for 14 days. Supermarkets impose buying limits. |

| 17-Mar-20 | Travel Ban | All international travel by Australian's banned. |

| 18-Mar-20 | Indoor Gatherings | Indoor gatherings > 100 banned. |

| 19-Mar-20 | Monetary Response | RBA reduces cash rate to record low of 0.25%. |

| 21-Mar-20 | Further Restrictions | Travel ban for non-citizens and non-residents from entering. Strict 4sqm social distancing rule imposed. |

| 22-Mar-20 | JobSeeker | $66b assistance package announced (primarily JobSeeker policy) |

| 23-Mar-20 | Lockdown Begins | Bars, clubs, cinemas, places of worship, casinos and gyms are closed. Schools start to close. |

| 25-Mar-20 | All Borders Closed | Australia closes its borders to all travel. Majority of states close borders for domestic travel (New South Wales, Victoria and Australian Capital Territory remain open). |

| 26-Mar-20 | Further Lockdown | Restaurants, cafes, food courts, auction houses are closed; house inspections banned. Weddings restricted to 5 people; funerals to 10. |

| 29-Mar-20 | Lockdown Peak | Stay at home other than for food shopping, medical or care needs, exercise or work/education that cannot be done at home. Max of 2 people together in public. |

| 30-Mar-20 | JobKeeper | $130b financial assistance (primarily JobKeeper wage subsidies backdated to 1 March). Six month moratorium on rental evictions. |

| 2-Apr-20 | Free Childcare | Childcare will be free for all workers during the Covid-19 crisis. Supermarkets impose instore limits on customer numbers. |

| 5-Apr-20 | Easter Stay at Home | Australians urged not to go on Easter holidays and to stay at home. |

| 7-Apr-20 | Commercial Rents | Mandatory Code of Conduct for commercial tenancies. |

| 17-Apr-20 | Aviation Assistance | Guaranteed domestic aviation network to capital cities and regional centres. |

| 21-Apr-20 | Medical Easing | Restrictions on elective surgery will gradually ease from Tuesday 28 April. |

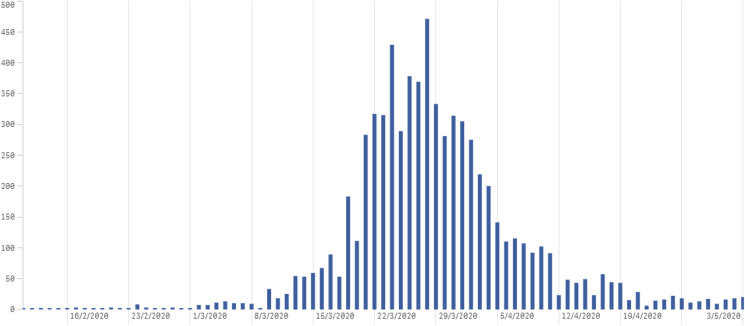

The evidence is that these measures, and the willingness of the Australian public to adopt the recommended behaviours, have been successful in turning around the growth of COVID-19 transmission. Following the highest recorded number of 469 new cases on the 29th of March, the number of new cases has fallen, indicating that that curve has initially flattened in Australia. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of daily new cases as per the Australian Department of Health (2020). As of the 3rd of May when this paper was written, Australia has had a total of 6801 reported cases of COVID-19, and 95 deaths.

Fig. 2.

Daily number of reported cases.

1.2. Aggregate impacts: Work and travel

While Australia has, to this stage, been relatively successful in battling the health risk presented by COVID-19, the impact on the economy has been just as large. Based on a recent survey conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS, 2020), the number of people who were working paid hours fell from 64% prior to the restrictions, to 56% in the first week of April, with a total possible increase in unemployment of 1.5–2 million people as a result of COVID-19 and associated measures.

In response to the economic shocks, governments at all levels have announced unprecedented levels of support. On the 22nd of March the Federal Government announced the $550 JobSeeker supplement for those on unemployment benefits, to remain in place for up to six months. This was followed by the $130 billion JobKeeper initiative announced on the 30th of March designed to keep employees attached to their place of employment, with $1500 per week being made available for eligible employees and paid via their employer. Along with a range of other measures designed to support the economy, the Federal government has committed to approximately $320 billion in stimulus spending, approximately 16.4% of annual GDP (Treasury, 2020). Similarly state governments have also injected money into the economy, for example NSW announced $2.3 billion in spending on the 17th of March, followed by a further raft of measures on the 27th of March.

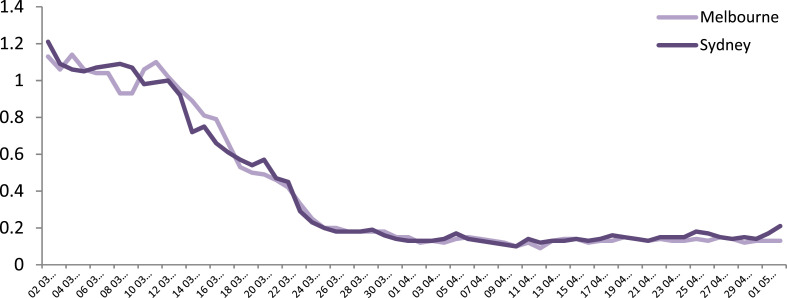

The impact of COVID-19 mitigation policies on the movement of people has also been significant. For example, Fig. 3 displays the CityMapper Mobility Index (2020), an aggregate measure of use of public transport, walking and cycling, over the last three months, and demonstrates a large change in both Sydney and Melbourne.

Fig. 3.

CityMapper mobility index.

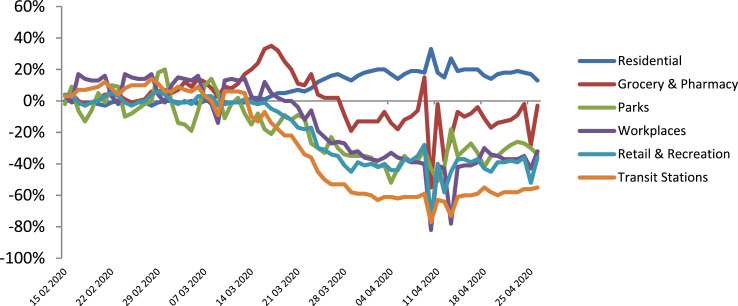

The Google Community Mobility Report (2020) uses location data from mobile phones to highlight the percent change in visits to places like grocery stores and parks within a geographic area, relative to baseline travel. As can be seen in Fig. 4 which aggregates this information for Australia as a whole, the amount of time spent at home has increased, while that spent at workplaces, retail and recreation, and transit locations has fallen dramatically since mid-March.

Fig. 4.

Google mobility report for whole of Australia.

In order to gain insight at a more disaggregate level, we deployed a survey examining household travel and activity patterns, employment and working from home, aviation travel, experiences in grocery shopping and general attitudes towards COVID-19. In the next section we give an overview of the survey and discuss the sample, followed by a presentation of preliminary findings, then ending with a discussion of the results and concluding remarks. This survey is the first of a series we are undertaking to track responses over time to the COVID-19 pandemic and how to monitor how Australia is responding as we move out of the most severe restrictions to the ‘new normal’.

2. Survey and data collection

The survey was designed in the last week of March, and asked respondents to provide information on their level of employment prior to the COVID-19 outbreak as well as after, including their ability and instances of working from home. Respondents were then asked to think about weekly travel activity of the household in the early part of March, prior to the emergence of COVID-19 as a significant public health threat, and to complete a short travel activity survey asking them to recall what trips the household made by different modes of transport and for different purposes. They were then asked if the household had changed their travel activity as a result of COVID-19 and if the answer was yes, they completed a second set of travel questions outlining the changed travel. For those that had not changed but had plans to do so, and those who had changed and planned even more, they also completed a travel diary asking what their planned change might look like.

Outside of travel activity, questions were also asked about the level of car use of the household, their level of comfort with using public transport given new biosecurity concerns, behaviours with respect to potential air travel and the nature of disruption to that activity, experiences with grocery shopping and a series of attitudinal questions about the threat of COVID-19 and the response of governments, businesses and people in general.

The online panel survey company PureProfile was used to sample respondents, and the survey was available across Australia in order to examine the widespread impact of COVID-19. The survey went into the field on the 30th of March and a sample of 1073 usable responses was collected by the 15th of April, 2020. A summary of the final sample is provided in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Overview of survey sample.

| New South Wales | 22% | ||

| Female | 52% | Australian Capital Territory | 2% |

| Age | 46.3 (σ = 17.5) | Victoria | 28% |

| Income | $92,826, (σ = $58,896) | Queensland | 22% |

| Have children | 32% | South Australia | 11% |

| Number of children | 1.8 (σ = 0.8) | Western Australia | 11% |

| Age of children | 11.2 (σ = 8.6) | Northern Territory | 1% |

| Tasmania | 2% | ||

It should be noted that the majority of questions in the survey were based on the behaviour and attitudes of the individual respondent, however the travel activity diary asked the respondent for information about trips at a household level (subsequent waves will look at individual-based travel behaviours). For the purposes of preliminary analysis, socio-demographics differences are explored based on gender, age (younger (18–34, n = 322); middle-age (35–54, n = 352); older (55 or older, n = 410)), and household income (lower income (less than $100,000, n = 617); middle income ($100,000 to $200,000, n = 276) and high income (more than $200,000, n = 121)3 .

3. Results

3.1. Impact of COVID-19 on travel

The survey went into field on the 30th of March, when the most extreme of the Australian social distancing measures came into effect. At this point in time, 78% of respondent households had already made many changes to their weekly household travel (females more likely to report that changes had already been made), 15% had not made changes nor were they planning any (lower income households more likely to not have changed) and 7% were planning to change (men more likely to report changes being planned). Of those households who had already changed, 32% were planning further changes moving forward (with younger households more likely to be planning further change).

The following sections report reductions in overall travel, travel by modes and travel for different purposes. Similar work is being completed globally, and one such of interest is a project of IVT, ETH Zurich and WWZ, University of Basel, the MOBIS-Covid19 study.4 This study uses mobile phone GPS tracking data from 3700 participants who completed a prior mobility study in between September 2019 and January 2020, to examine the impact of COVID-19 on the French and German speaking part of Switzerland. Our results, using a household travel survey, are consistent with those found via the MOBIS GPS tracking, as well as those found by aggregate location data in Australia such as Google and CityMapper.

Note that we present weekly averages for three periods of time; an normal week prior to COVID-19 (Before COVID-19), travel for the week preceding the completion of the survey (Data Collection), and any further changes to travel the household was planning in the week following the completion of the survey (Planned Changes). Refer to Fig. 1 for timeline of events.

3.1.1. Overall travel

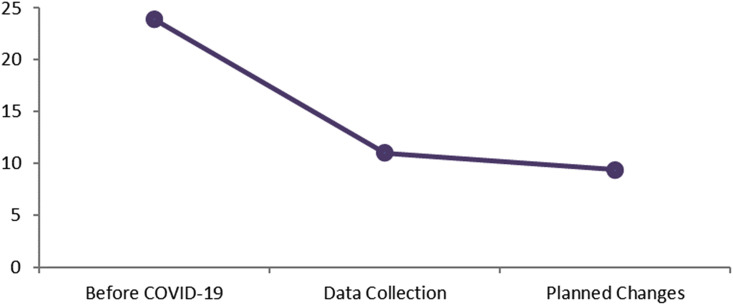

Consistent with information provided by more aggregate sources such as Google Mobility Reports and CityMapper, we find that reported trips have reduced significantly from an average of 23.9 trips per week (for different purposes using different modes) down to 11.0, a reduction of over 50% in weekly household trips (Fig. 5 ). Moving forward, planned further changes were marginally different to those that had already occurred, averaging 9.4 per week.

Fig. 5.

Impact of COVID-19 on reported household weekly trips.

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, younger households made significantly more trips than middle and older aged households, and middle aged households in turn made significantly more than older households. During the data collection period, the number of trips made per week by middle and older households were no longer different; however younger households while making less trips, still reported making significantly more than middle and older households. With regards to further changes planned, younger households still planned more weekly trips on average than older households, but planned to revise the number of trips down to similar levels to middle aged households.

Lower income households made significantly less trips per week than middle or higher income households prior to COVID-19; however during the data collection period this difference largely disappeared as households of all incomes reduced the number of trips made.

3.1.2. Travel by mode

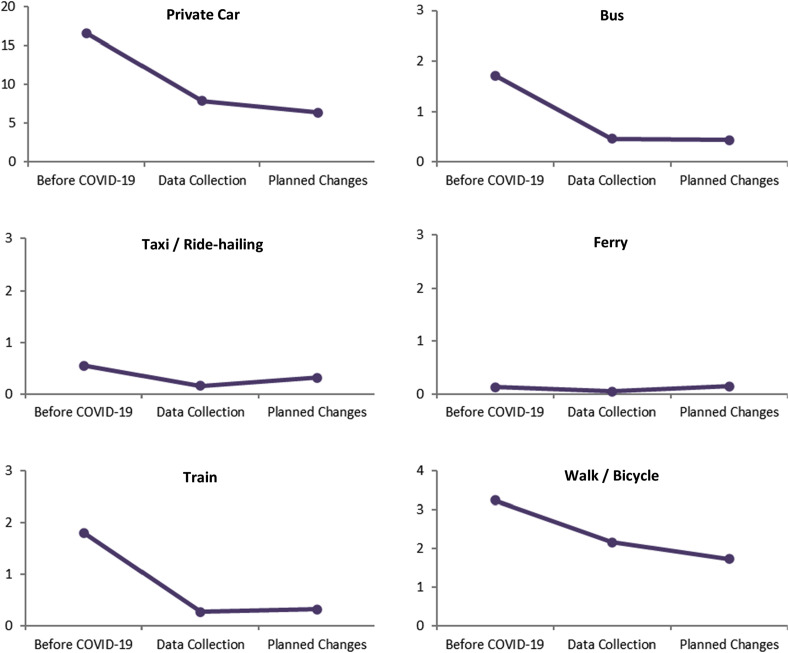

In terms of how different modes of transport are affected by changing travel behaviours (Fig. 6 ), the biggest reduction in aggregate trips was via the private car, falling from an average of 17 trips a week down to eight. Similarly, the use of public transport has also fallen, with significant reductions in train and bus usage.

Fig. 6.

Reported weekly household trips by mode.

Interestingly, as a proportion of overall household trips, the private vehicle remains relatively stable at around 70% before COVID-19 as well as during data collection, or for any planned future changes, but the use of public transport falls from around 15% of trips on average down to 7%. Active transport, while lower in absolute terms, increases from 14% of household weekly trips prior, to accounting for one in five (20%) of trips during the data collection period.

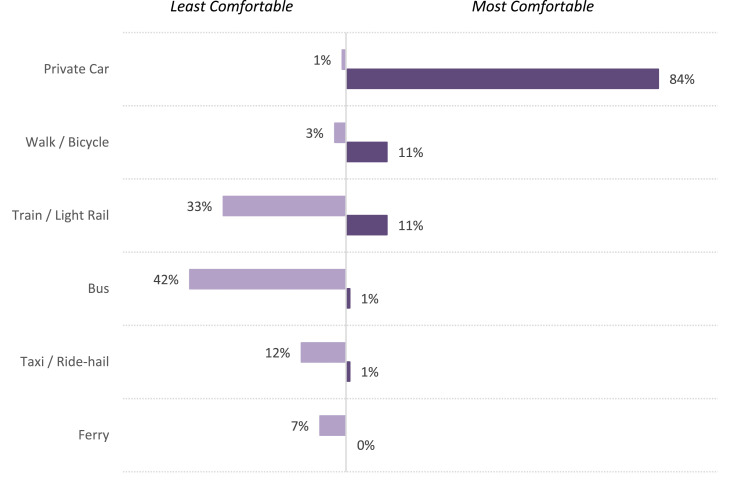

Looking at perceptions of different modes in a little more detail, respondents were presented with the following list of modes presented in Fig. 7 and asked to highlight which single mode they would feel most comfortable in using, and which one they would be least comfortable using, if they were required to travel (respondents could select any mode they thought to be most or least irrespective of ownership or availability). The figure highlights that the private vehicle is clearly dominant in terms of which mode a respondent would feel most comfortable. The perception of the train and bus are quite negative in the context of COVID-19 with 33% and 42% of respondents rating these modes as their least comfortable respectively. These perceptions are largely invariant to socio-demographics, with only middle age respondents displaying a greater propensity to rate taxi or ride-sharing as their most comfortable option.

Fig. 7.

Most and least comfortable mode of transport.

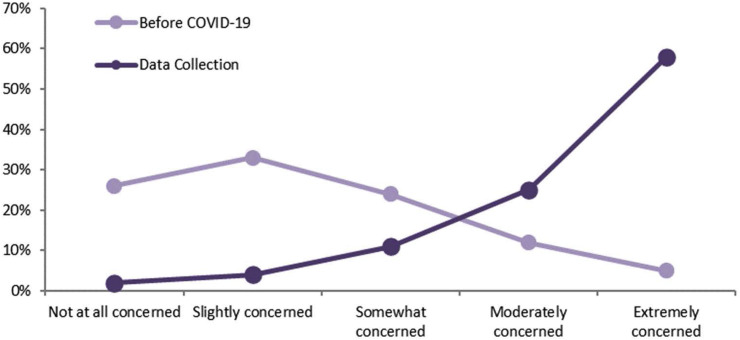

The impact of COVID-19 on public transport is further demonstrated when looking at how concerned respondents were about the level of hygiene on public transportation prior to the COVID-19 and during data collection (Fig. 8 ). Over half of respondents (58%) are now extremely concerned about levels of hygiene on public transport, up from just 5% prior to COVID-19. Again, these attitudes are largely invariant across the sample, with females being more concerned both before COVID-19 and during the data collection period, and older people who were significantly less concerned than others prior to COVID-19, but after restrictions hold the same concern as other age groups.

Fig. 8.

Level of concern about hygiene on public transport.

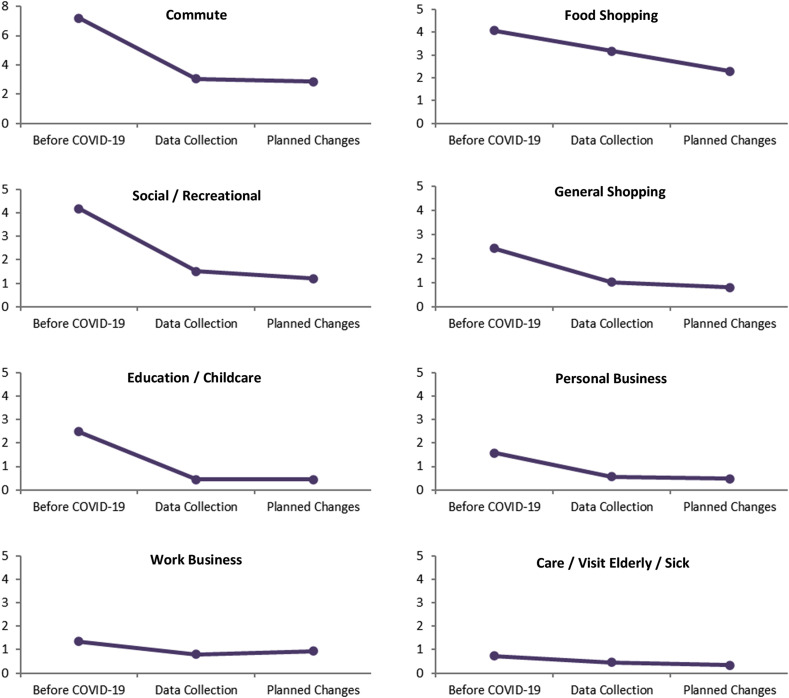

3.1.3. Travel by purpose

As seen in Fig. 9 , trips for all purposes examined have fallen, the biggest fall unsurprisingly being in commuting trips, from an average of seven per week down to three. In aggregate, significant falls are also observed for the purposes of childcare and education, social and recreation, general shopping, personal business and for purposes of caring for the sick or elderly. Interestingly, while the average number of food shopping trips falls from 4.1 per week before COVID-19, to 3.1 during the data collection period, this difference is not significant, due mainly to the large degree of variability in how often households engaged in food shopping both prior to COVID-19 and after the outbreak. This may also be a result of some households building up stockpiles of food in the early stages of “panic buying” while others did not (discussed in Section 3.5). Again, as a proportion of household trips, commuting remains relatively constant at approximately 30% of all household trips, with falls in childcare and education (from 10% to 4%) and social and recreation (18%–13%), but food shopping now accounts for 29% of trips (up from 17%).

Fig. 9.

Reported weekly household trips by purpose.

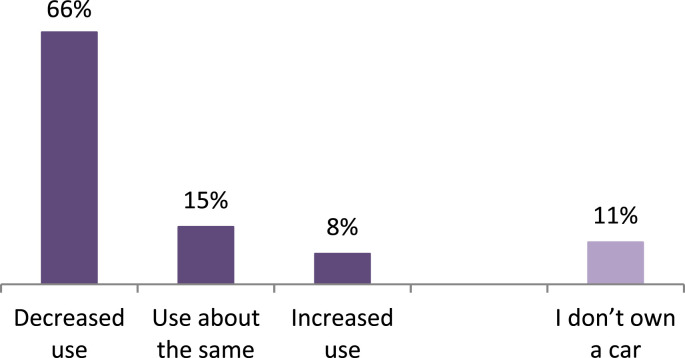

3.1.4. A closer look at car travel

While Fig. 6 shows a fall in the number of trips made by car to be approximately 50%, Fig. 10 below shows that two-thirds of respondents (66%) report a reduction in household car use, 15% having car use that is about the same, and 8% of households report using their car more. Females are more likely to report a decrease in household car use, along with older respondents. Low income or younger households, however, are more likely to not own a car or less likely to report decreased car use.

Fig. 10.

Changes in car use over previous week.

Overall, car use as a percentage of kilometres driven has decreased by 35% in aggregate (standard deviation = 42%). Among those households to have decreased their car use, the estimated reduction is 60% on average (median = 60%, standard deviation = 27%); lower income households report a significantly lower average reduction, with high income households reducing car use the most. In terms of the small number of households who have increased car use, the average increase is 44% (median = 35%, standard deviation = 30%).

To explain these broad changes in use of the car, a series of ordered logit models (Greene and Hensher, 2010) were estimated, where the ordered choice were based on the response to a question that indicated whether a respondent would be more or less likely to decrease car use (0), keep car use constant (1), or increase their use of the motor vehicle (2). Many covariates were tested, and the best model is presented in Table 3 .5 A full range of socio-economic and demographic variables were trialled and found not to be significant and were excluded from the model. The reduction in car use has been widespread over all demographics, and indeed what this model actually shows is that it is the ability to do work from home and the support of the employer to do so, that really determines WFH and thus reductions in car use, rather than industry, occupation, age, gender or income per se. In explaining a broad change in car use, we found statistical significance associated with being able to do work from home, being directed to work from home by the employer, and where the car was the main mode of transport to work prior to the outbreak of COVID-19.

Table 3.

Ordered logit model explaining changes to car use.

| LLModel | −864.17 | ||

| LLBase | −896.30 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.04 | ||

| χ2 | 64.25 | ||

| AIC | 1742.30 | ||

| nobs | 1073 | ||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Err | Z value |

| Constant | 0.20 | 1.27 | 0.20 |

| Directed to work from home | −1.08 | 0.20 | −5.30 |

| Work can be completed from home | 0.001 | 0.0002 | 4.69 |

| Commute by driving car (prior) | −0.84 | 0.18 | −4.67 |

| Resides in Western Australia | −0.40 | 0.22 | −1.82 |

| Commute by bus (prior) | 0.44 | 0.27 | 1.57 |

| Threshold Parameterμ1 | 1.90 | 0.11 | 17.53 |

The mean direct elasticities presented in Table 4 provide insights into the impact of the variables on car use. If someone is directed to work from home by their employer, on average there is a 34% increase in the probability of a household decreasing their use of the car. Similarly, if someone's work can be completed from home, or if they mainly used the car to commute prior to COVID-19 or if they live in Western Australia, the probability of the household decreasing the use of their car also rises (and conversely for these variables, the probability of car use staying the same or increasing is lower for these households). Though the effect is relatively weak, if a bus was the main mode of commuting prior to COVID-19, the probability of car use staying the same, and particularly increasing car use, is higher. This is likely due to the high level of discomfort attached to bus travel,6 and concern over the relative hygiene of that mode; with the preference now being for the hygiene of their own vehicle.

Table 4.

Elasticities from ordered logit explaining changes to car use.

| Variable | Decrease | Same | Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directed to work from home | 0.34 | −0.52 | −0.63 |

| Work can be completed from home | 0.11 | −0.16 | −0.23 |

| Commute by driving car (prior) | 0.14 | −0.21 | −0.27 |

| Resides in Western Australia | 0.30 | −0.43 | −0.62 |

| Commute by bus (prior) | −0.17 | 0.23 | 0.40 |

While the number of significant explanatory variables at this aggregate level is small, there are more factors when examining the magnitude of the change. Given that two-thirds of households have decreased the use of their car, we opt to look at this change in detail in this paper as there is preliminary evidence that cars will be relatively more attractive when travel restrictions are eased. It should be noted that the model fits are low, primarily because of the uniformity in the way in which the sample adapted their travel and car use in order to combat Covid-19. To use an Australian term, agree or disagree with the measures, it appears that people have complied with government recommendations.Where commuting was undertaken primarily via bus, the probability of increasing car use increases (and conversely the probability of reducing the use of the bus is less). This result, combined with the findings that respondents would be least comfortable travelling on buses (followed by trains), and that 83% of the sample express concern about hygiene on public transport, indicates a likely high aversion to public transport at least in the short term. Additionally, the likely reality is that capacity on public transport will be significantly reduced due to social distancing requirements, creating a further disincentive for these modes. As people return to work, the attractiveness of the private vehicle may create worse congestion than what was seen prior to COVID-19, so understanding why people are decreasing car use is important in being able to develop policies to keep use suppressed as restrictions are eased.

Table 5 presents the results of a regression modelling examining drivers of decreased car use.7 Again we see that the large drivers of reduced usage are changes to work and important life activities, which is expected. Those who did more days working prior to COVID-19 (compared to the data collection period) report a higher percentage decrease in the overall number of trips after the outbreak (the dependent variable is negative to represent a percentage drop). Those who worked more days from home after the outbreak than before, have a higher percentage decrease than those who work from home the same amount or less. Respondents who reported that shopping activities and meeting with friends were usual activities that had been interrupted by COVID-19 reported significantly decreased car use relative to others, as did those who felt that the outbreak was a significant threat to the health of the economy (possibly supporting this view through decreased car use). Individuals who could not work from home had significantly less reduction but still a decrease, in car usage (recall that these people were also more likely to keep car use the same or increase it), and those who agreed more strongly that COVID-19 is a significant public health threat reduce car use by a lesser percentage.

Table 5.

Explaining the magnitude of decreased car use.

| R2 | 0.101 | ||

| Adj. R2 | 0.091 | ||

| F(8,689) | 9.700 | ||

| Fsig | 0.000 | ||

| Std. Err. Est. | 25.905 | ||

|

| |||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Err | t value |

| Constant | −34.27 | 3.90 | −8.79 |

| Difference in days of employment (Prior vs Data Collection) | −3.08 | 0.50 | −6.13 |

| Difference in days worked from home (Prior vs Data Collection) | 3.07 | 0.50 | 6.13 |

| Shopping affected by COVID-19 outbreak | −7.52 | 2.42 | −3.11 |

| Meeting friends affected by COVID-19 outbreak | −6.93 | 2.78 | −2.49 |

| Work cannot be done from home | 7.02 | 2.68 | 2.62 |

| Drive car as main mode (Prior) | −7.51 | 2.77 | −2.71 |

| COVID-19 is a threat to public health | 1.24 | 0.52 | 2.40 |

| COVID-19 is a threat to economic health | −1.23 | 0.52 | −2.38 |

These findings align well with what we are seeing in the grey press and media about the challenges in making public transport attractive again. In Australia, service levels and schedules were unchanged during COVID-19 with resultant movement of almost empty carriages and buses. Public transport Authorities are already planning new strategies to support public transport which include regular deep cleaning and enforcing the wearing of masks while on board, on platforms and at public transport terminals. Social distancing will mean that seats adjacent to passengers must remain unfilled, dropping passenger capacity to around 30 percent for most public transport modes. The latter may indeed be acceptably achievable if working from home continues at a rate that might not be as high as at present but substantially higher than prior to COVID-19. With offices obliged to comply with social distancing rules as restrictions are lifted, the staggering of working hours is likely to provide some support in achieving a public transport system that is no longer typified for the high peaks (the camel effect), but rather becomes like the horse (flat throughout the day).

3.2. Impact of COVID-19 on work

3.2.1. Employment

A large driver of travel activity is employment, and there is no doubt that COVID-19 has had a large impact on the availability of work and the way in which work is done. With changes to retail and shopping behaviour already occurring due to COVID-19, the restrictions on trading announced by the Federal government, coming into effect on the 30th of March, had further impacts on the economy.

Fig. 11 highlights just how widespread these impacts were, with only one-third of respondents being unaffected or perhaps more impactful, 70% were impacted by the regulations or knew someone who was. Females were more likely to either be impacted or know someone who was, and respondents from high income households were more likely to have someone in the household affected (and low income less likely).

Fig. 11.

Impact of government regulations on availability of work.

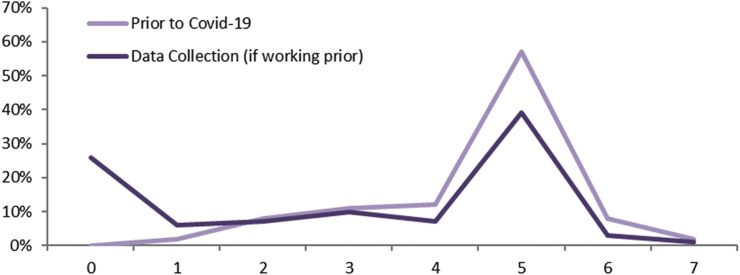

In this sample, 33% of respondents were not working prior to COVID-19 (either retired, or a stay at home parent, or unemployed); but looking at only those who work at least one day a week, prior to COVID-19 more than half of respondents worked 5 days per week (57%), with the average among those working being 4.5 days a week. However, during the data collection period, over a quarter of respondents (26%) are no longer employed and the number who work 5 days per week has fallen dramatically to 39%, as can be seen in Fig. 12 . Younger households and those on lower incomes are impacted more heavily as a result of COVID-19, with these two groups now working significantly less days per week on average than other respective age and income groups. These unemployment results may seem high, given the implementation of the JobKeeper scheme, designed to keep employees connected their place of work. However, this support package was announced on the day the survey went into field, and we unfortunately do not have any questions in this wave pertaining to either JobSeeker or JobKeeper.

Fig. 12.

Days Worked per Week (if employed prior to COVID-19).

3.2.2. Working from home

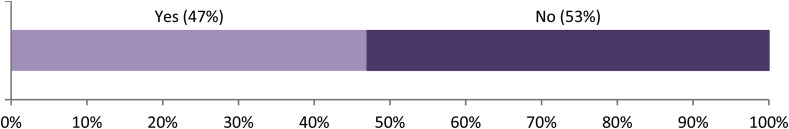

For those who still have employment, many have been able to shift their work such that they are now working from home. As shown in Fig. 13 , almost half of those employed have stated that their work can be done from home (47%), with those from higher incomes or from middle aged households being more likely to be able to complete their work from home.

Fig. 13.

Ability to complete work from home.

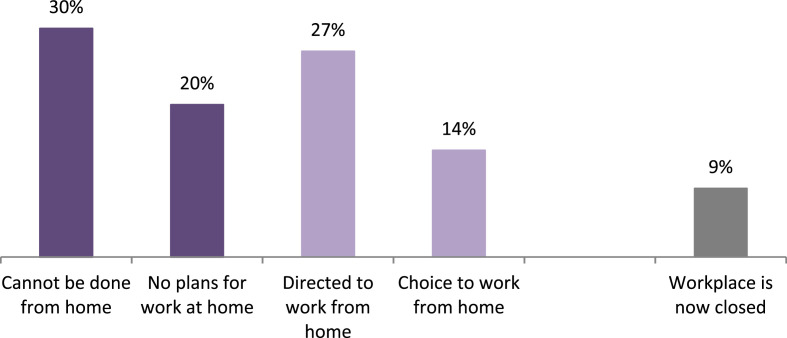

In terms of the policy of the workplace in which respondents are employed (Fig. 14 ), 41% are in workplaces that either direct employees to work from home, or give them the choice to do so; half either cannot work from home given the nature of the job or their workplace does not support it, while 9% unfortunately work for a business that has now closed as a result of COVID-19. Many of the latter businesses are restaurants, pubs, clubs, gyms, tattoo parlours and shops.

Fig. 14.

Workplace policy to working from home.

In terms of differences based on socio-demographics, females are more likely to have worked in places that have closed, those in lower income households or respondents who are younger are more likely to be in workplaces that have no plans to allow working from home or in jobs where work cannot be done from home, and higher income households are more likely to either be given the choice or directed to work from homes.

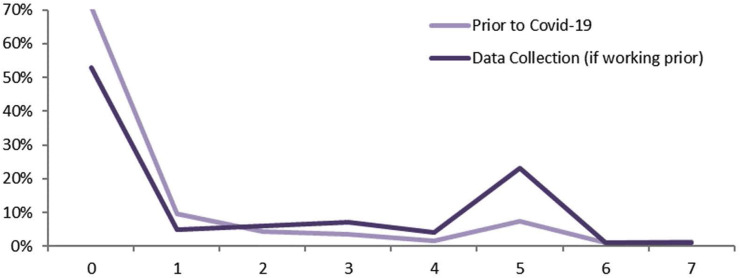

Prior to COVID-19, of those who were employed, the vast majority did not work from home (71%); however following the COVID-19 restrictions, that number almost halved (down to 39%), with a quarter of respondents now working from home five days a week, see Fig. 15 . As a result the overall average number of days worked from home per week swelled to 2.5, up from 0.8 days prior. While middle aged respondents work more from home on average (both prior to and during data collection), the number of days worked from home is independent of age, gender or income.

Fig. 15.

Number of days working from home.

3.3. Impact on activities

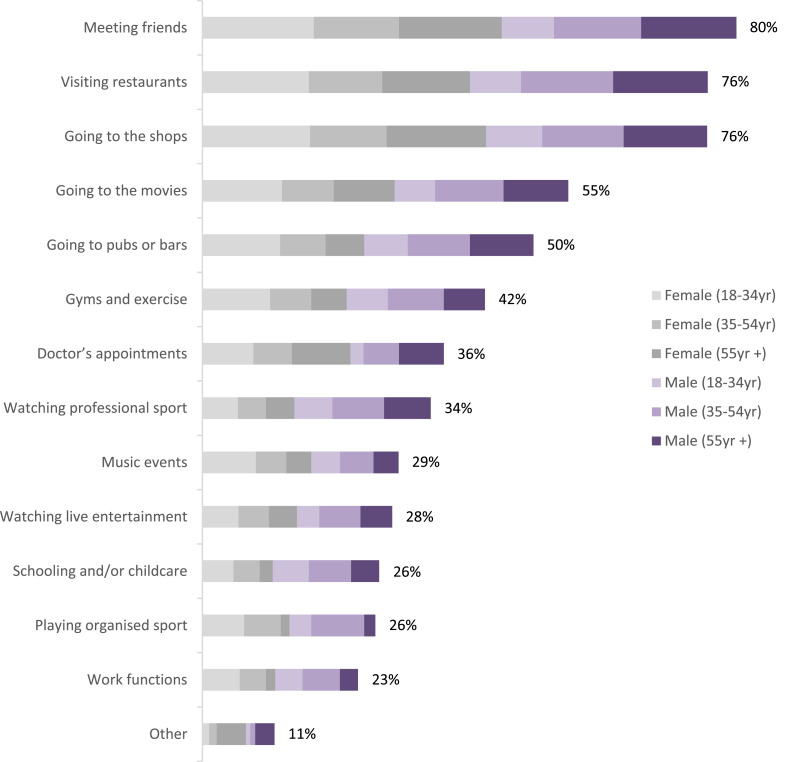

The impact of COVID-19 on regular activities outside of work has been just as profound (Fig. 16 ), with large numbers of respondents reporting interruptions to meeting with friends (80%), visiting restaurants (76%), and going to the shops (76%). Interestingly, only 34% of the sample stated that watching professional sport was a regular activity that had been interrupted, possibly because many do not watch these events.

Fig. 16.

Interruption to normal activities due to COVID-19.

There are many differences in the impact based on socio-demographics. Females are more likely to state that meeting with friends, going to the shops, and doctor's appointments had been interrupted; males that watching professional sport or playing organised sport had been interrupted. Younger respondents were more likely to report interruptions to going to the shops, going to movies, going to pubs or bars, gyms and exercise, and attending music events; middle-aged respondents are more likely to experience disruption to schooling or childcare; and generally older respondents report less disruption overall, with the exception of doctor's appointments where they are more likely than other age groups to have this activity disrupted.8 With respect to income, lower income households are less likely to report disruption to visiting restaurants, going to pubs or bars, gyms or exercise, watching professional sport, playing organised sport, or work functions; middle income households were more likely to find that going to restaurants and pubs or bars has been interrupted; and higher income households were more likely to report disruption to gyms and exercise, watching professional sport and work functions.

3.4. Impact on air travel

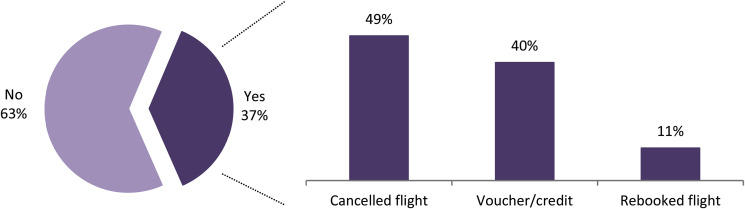

Another point of interest in this survey was the impact on the aviation industry. As at the end of the first week of April, only 2% of the survey was still planning on making a flight of some kind, with 52% delaying travel voluntarily and 46% doing so because of government regulations. For those who still intended on travelling, 63% were going to do so domestically, while 54% were still intending to make international travel during the COVID-19 pandemic (selecting both was possible). The majority of intended travel was personal travel (79%) as compared to business (29%).

Fig. 17 highlights the bigger impact on planned air travel that has been disrupted by COVID-19, with over a third (37%) of respondents experiencing some kind of disruption to their planned travel. Unlike travel that was still intended, interrupted travel was primarily international (63%) compared to domestic (55%), and almost all personal travel (94%) rather than for business (12%). Almost half of respondents cancelled travel (49%), a large number returned the ticket for a voucher or credit with the airline, with 11% having rebooked their flights for a later date. Females are more likely to have returned their ticket for a voucher or credit.

Fig. 17.

Air travel interrupted by COVID-19.

3.5. Impact on shopping

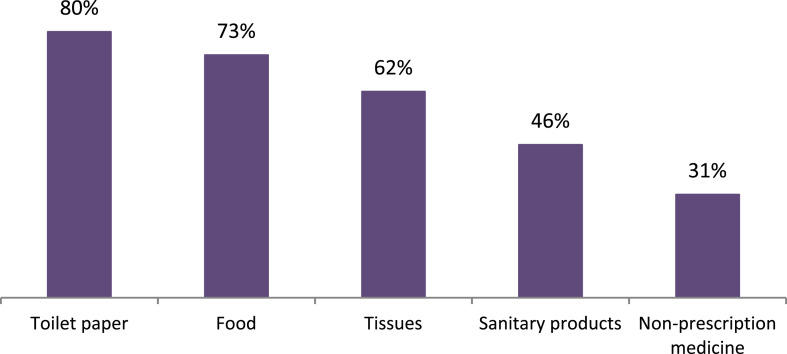

The COVID-19 outbreak resulted in widespread instances of panic shopping, particularly for toilet paper, sanitizers, and staple foods such as pasta, rice and minced meats. The survey asked respondents if they encountered difficulty shopping for a number of key items, and Fig. 18 shows that 80% of respondents experienced problems shopping for toilet papers, along with food (73%) and tissues (63%). Females were more likely to report difficulty in shopping for toilet paper, food and non-prescription medicine, and males more likely to report shopping for sanitary products. Interestingly, older respondents were less likely to report difficulty in shopping for food, sanitary products and non-prescription medicine, perhaps due to supermarkets (as of the 16th of March) providing shopping time between 7am and 8am exclusively for older people and those with disabilities.

Fig. 18.

Difficulties shopping for items (Y).

Almost a quarter of respondents were using online grocery shopping prior to the 1st of March, and a further 18% reported using online grocery shopping as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak; though older households were less likely to use it both before the pandemic and during the data collection period.

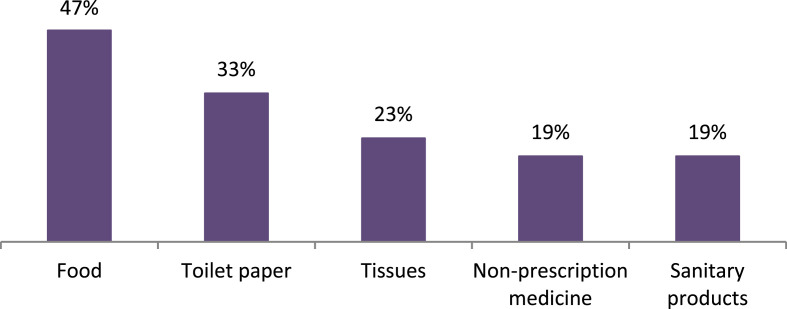

The survey also explored if respondents engaged in any “stocking up” behaviour themselves (Fig. 19 ), and almost half the sample (47%) reported doing so for food, and one-third for toilet paper. Older respondents were less likely to have stocked up on food or sanitary items, and lower income households less likely to have stocked up on toilet paper.

Fig. 19.

Stocking up on selected items (Y).

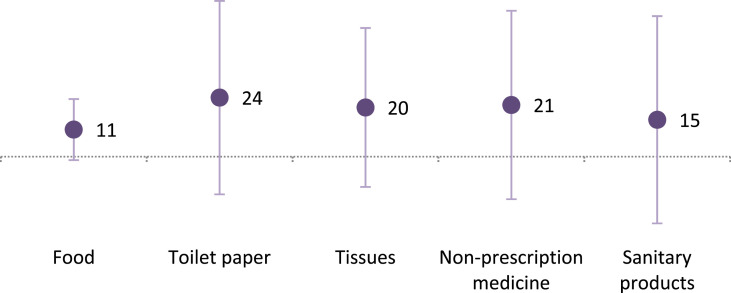

In terms of the number of days of stock for each of these items, there was a great degree of variability in the data (as indicated by the error bars in Fig. 20 ), but households held an average of approximately three weeks of stock for toilet paper, tissues and non-prescription medicines. Stock of food was the most consistent among responding households, estimated to be at a week and a half of supplies. Females reported a higher average number of stocked sanitary items; older people a higher average stock of food and less sanitary products, and higher income households holding a higher average stock of non-prescription medicine.

Fig. 20.

Average days stock of selected items.

Interestingly, when looking at the variation in household supplies, 7% of households reported having only one day of food in stock, whereas 2% reported having two months or more. With respect to toilet paper, 10% felt they only had enough stock to last a day compared to 11% who felt they held two months or more worth of supplies. Twenty percent of households reported only having one day of tissues and 9% having two months or more; 27% one day of non-prescription medicines and 9% two or more months; and lastly 32% report one day of sanitary products compared to 5% feeling they hold two or more months of supply.

3.6. Attitudinal analysis

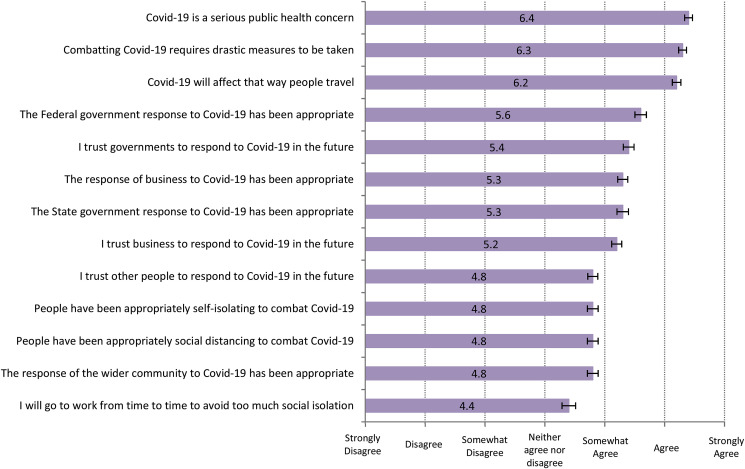

The survey also explored the attitudes held towards various aspects of the COVID-19 outbreak with respondents asked to state their level of agreement with a number of statements (Fig. 21 ; error bars represent 95% confidence interval). Across all statements, respondents exhibit significant levels of agreement, however the thought that COVID-19 is a serious public health concern, requires drastic measure and will affect the way people travel is significantly higher than other statements. On the other hand, agreement with the statement that I will go to work to avoid social isolation is significantly lower than all other statements. Interestingly, there is significantly lower agreement with the trust in other people to respond in the future, the appropriate self-isolating and social distancing of others and the response of the wider community, as compared to the response of the governments and business and their actions moving forward.9

Fig. 21.

Level of agreement with statements regarding COVID-19.

In terms of sociodemographic differences, older respondents reported significantly higher levels of agreement across all statements; females higher average agreement with COVID-19 being a serious public health concern, requiring drastic measures, that it will affect how people travel, that the response of business has been appropriate and that the response of the state government has been appropriate. Males and middle income respondents exhibit significantly higher average agreement with the statement that they will go to work from time to time to avoid social isolation.

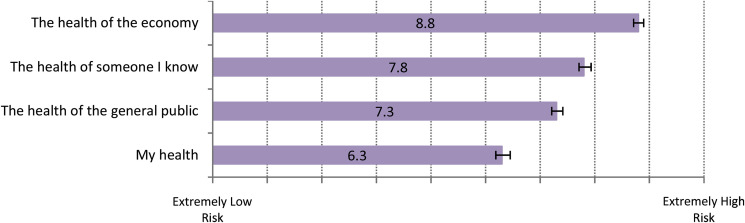

With respect to the risk that COVID-19 presents (on a scale from 1 = extremely low risk to 10 = extremely high risk – Fig. 22 ; error bars represent 95% confidence interval), the risk of COVID-19 to the health of the economy is viewed to be significantly higher than the risk to someone known to the respondent, the general public, or the health of the respondent themselves. However, COVID-19 is still thought to be a very high risk to someone known to the respondent or themselves; indeed while respondents do view COVID-19 as a risk to themselves, on average their own health is at the lowest perceived risk.

Fig. 22.

Risk of COVID-19 to human and economic health.

In terms of socio demographic different, older respondents exhibit significantly higher levels of agreement that COVID-19 is a threat to “my health” (and average of 1 unit higher than both younger respondents and those in the middle age group). Interestingly, older people also exhibit significantly higher agreement that the virus is a threat to the economy than younger and middle aged respondents. There are no differences in terms of gender or household income.

4. Discussion of policy implications

4.1. Overview of results

The changes brought by the COVID-19 outbreak are widespread and unparalleled. Following the restrictions announced by National Cabinet implemented on the 30th of March, we can see that travel activity has significantly decreased, as a function of a reduction in travel via every mode, and for every purpose. This evidence suggests that the government's request to ‘stay at home’ has been heeded. Early modelling of COVID-19 indicated that a level of compliance with recommended guidelines below 70% would be unlikely to succeed, whereas compliance with social distancing measures at a 90% level would likely control the disease within 13–14 weeks, when coupled with effective case isolation and international travel restrictions (Chang et al., 2020). National COVID-19 statistics provide tentative evidence that this changed behaviour has been effective thus far in “flattening the curve” of COVID-19 infection rates, indicating that compliance has been strongly embraced within Australia.

Attitudinal analysis provides some broad insight into why Australia has been relatively successful in combatting COVID-19 thus far; our results indicate that the virus was widely viewed as a serious public health concern that required drastic action, particularly disruption to travel, as it presented a health risk to someone that they knew. While there may have been an underlying motivation to comply with national guidelines for altruistic reasons, there equally may also be the realisation that COVID-19 presented a threat to the economy and that decisive action would be needed to minimise that economic impact. Our data indicates that in these early stages, the general mood was one of support of the actions taken by Federal and State governments, and the response of business to the COVID-19 impact.

The rest of this section will address each of the areas of analysis in the preceding section, looking to extract further insight and to interpret the findings in the context of potential policy implications for both dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, but also thinking about what could be implemented for other pandemic events which may occur in the future.

4.2. Food logistics and freight

Significant disruption was witnessed in grocery shopping, with large numbers experiencing difficulty shopping for toilet paper and food, with many stocking up on both. While not ostensibly related to human transport and mobility and transport behaviour, it is an interesting highlight of the human response to the COVID-19 pandemic and does have significant ramifications for freight transport policy. It should be noted that there are no food security problems in Australia with approximately 71% of what is produced in Australia being exported, and 11% of what is consumed in Australia being imported (ABARES, 2020) so the predominant concern is about timely logistics responses.

Learning from COVID-19, future pandemic situations will need to see a swifter implementation of purchase limits on staple items and a designated shopping time for the elderly and disabled to be created sooner, along with anticipating a likely surge in demand for staple items popular in home-cooking. This has implications for early stage planning, particularly around staffing and inventory requirements. A major policy implication of COVID-19 has been the response of the Australian Consumer and Competition Commission, temporality suspending anti-competition regulation to allow supermarkets to coordinate with each other when working with manufacturers, suppliers, and transport and logistics providers (though still prohibiting price fixing). This sets a precedent for early stage cooperation in future pandemic scenarios.

Overall, the implementation of these policies seemed to stabilise the buying behaviour during the data collection phase for this survey suggesting that results households have enough stock of necessities to cope with disruption, though stock levels are variable and food stocks are relatively lower at an average of 11 days10 . The supply chain operations of supermarkets and producers have seemingly caught up with rapidly changing demand, but should remain prepared for future disruptions which might occur.

4.3. Aviation sector

The aviation industry, like all industry, has experienced dramatic upheaval. At the time of sampling, only 2% of people still intended to make a flight and over a third of people had air travel disrupted by COVID-19, with the majority of this group cancelling flights for a refund, or suspending bookings in return for a 12 month credit with the airline. How good that credit might be could be questionable, for example Virgin Australia has gone into voluntary administration, brought on as a result of COVID-19. Most of the interrupted travel was personal travel, and more was for international travel than domestic.

With state and international borders closed, air travel is significantly reduced. It is unclear exactly when international borders will reopen, perhaps the most definitive trigger for relaxation of global travel restrictions will be the advent of a vaccine but that is at least 12–18 months away, ignoring the further time it would take to mass produce a vaccine on the scale that would be required. There is very little indication as to how individuals will react. While some may be less inclined to travel, growth in international travel continued unabated under previous shocks like the Oil Crisis, Gulf Crisis, 9/11 attacks, and SARS (IATA, 2020).

The recent growth in air travel, however, has been predicated on the fact that international travel was becoming more affordable, thanks to new technology and fiercer competition in the industry. Yet, with a prolonged global recession there may be less competition in the sector moving forward and what was once affordable may no longer be so, and the number of competing airlines may well be less. While it is likely that preference for international travel may be suppressed, or unaffordable, for some time this will increase the relative attractiveness of domestic travel. To that end, Australian-based airlines will likely need to investigate, and have already started to do so, strategies to encourage air travel within Australia, perhaps working with state-based tourism organisations to develop package deals for consumers, or advertising about tourist destinations within national borders. Following the bushfires, there were many well received campaigns to travel and buy local, and the sector will need to recapture that momentum and sense of ‘Australian-ness’.

4.4. Public transport

Public transport will face some of the greatest challenges if we are to make it attractive again as we emerge slowly out of the COVID-19 pandemic. In Australia, service levels and schedules were unchanged during COVID-19 with resultant movement of almost empty carriages and buses. Our results indicate a high degree of trepidation with public transport, particularly with respect to hygiene. To combat this, public transport authorities may need to consider overt demonstrations of “deep-cleaning” (possibly via social media platforms or service provider websites). There may also be the need to employ staff to provide visible cleaning while services are operational, such as cleaning surfaces regularly, or wiping down seats when passengers alight. Staff maybe deployed at stations or stops to encourage social distancing and efficient movement. It may also be beneficial to provide hand sanitiser at stations and onboard services. The purpose of these demonstrable actions are to reduce the level of concern with the overall cleanliness of each public transport mode, particularly with respect to the “threat” presented to the traveller by other members of the public, that they may not trust as much as people they know.

Clearly social distancing will need to be enforced on public transportation until restrictions are eased (in Australia the restriction is set at one person for every 4sqm of space). This will place very significant capacity constraints on the network. Lastly, public transport service providers may need to think about innovative technological solutions to make the public transport experience easier to engage with during the pandemic. They might perhaps look towards investment in the development of a service wherein prospective users can receive alerts about when a good time to travel is or when is a bad time, via a simple “green” or “red” indicator in a phone app.11

4.5. Motor vehicle and road use

Overall, car use is down by over a third (35%) and for the majority of respondents who were able to decrease car use, that reduction is even larger at 60% less than before COVID-19. The benefits of that reduction include improved air quality and visibility in our capital cities, and in less congestion on the roads for those essential workers who need to travel. However, our analysis indicates that it is likely that as COVID-19 restrictions ease, the car will return in a dominant way and could cause congestion at levels not seen prior to the outbreak should sensible measures not be introduced. Preliminary evidence in the Swiss MOBIS study shows the start of slow recovery in kilometres travelled by car (and a large increase in bicycle use) while public transport modes stay comparatively flat (Mobis, 2020).

Maintaining flexibility with respect to working from home and work starting and finishing times will be as important for road congestion as or public transport crowding, so transport authorities should be encouraged to lobby government and business to ensure that support for these working arrangements are in place for at least as long as restrictions stand. Innovative thinking may also need to occur, perhaps bus lanes might be given over to mixed traffic for the duration of the pandemic to facilitate traffic flow. If, as suggested by government, that temporary additional parking should be provided given the likely increase in car use, especially in central business districts, they must monitor parking providers to avoid price gouging behaviour. There may also be the opportunity to revisit older perhaps previously impossible policies such as car-pooling. With the likely increase popularity of the car, there may be mechanisms that can be designed to better coordinate car-pooling between known/trusted persons, for both work and recreational purposes, as the restriction on social-distancing and gatherings ease (i.e. more combined trips with those in your family or among members of social networks whose health can be “trusted”).

Transport authorities could perhaps leverage the current enjoyment of better amenity, combined with significant improvement to health as a result of less tailpipe emissions, to encourage lower levels of car use to be ongoing. Lastly, with interruptions to meeting with friends and shopping being a key contributor to reduced travel, authorities could also appeal to Australians to still be patient with regards to meeting friends and engaging in widespread discretionary shopping particularly during the week, as people do hopefully start to return to work, at a staggered time of day rate.

4.6. Active transport

There may be scope to encourage active transport, particularly for short trips, as a substitute for car use. If not given over to cars, perhaps bus lanes could be given to active transport modes and authorities should also consider removing restrictions on bicycle riding on footpaths (currently illegal in many states of Australia) within sensible parameters. Careful thought should be given to the bicycle networks within cities, and in strategic locations there may be scope to limit on-street parking to create “pop-up” bicycle lanes which, if successful, could become permanent infrastructure. Nascent modes such as e-bikes and e-scooters (which are currently illegal in New South Wales for example) could also receive policy and regulatory support for shorter trips, or perhaps with increased spacing between passengers on public transport, commuters could take these modes more easily onto public transport to improve access and egress at stops or stations.

In the longer term, authorities should use the COVID-19 pandemic as a starting point to think about embedding active transport within all transport infrastructure investment. In looking for infrastructure-based stimulus spending, thinking laterally about increased infrastructure for active transport such as improved bicycle lanes and accessibility would provide viable alternatives to car use. For example, as the WestConnex project continues (a 33 km, $16.8b toll road project in the west of Sydney), maybe some space can be provided for a bicycle super-highway next to the orbital, or bicycle lanes could be developed alongside heavy rail infrastructure and away from roads.

4.7. Flexible working arrangements

The way in which work is undertaken has changed; the number of people working zero days from home has fallen from 71% to 39%, and the number working five days a week from home has increased from 7% to 30%. Almost half of the sample have the ability to complete their work from home and have been either given the choice or been told to do so. The ability to work from home or staggering working hours is perhaps the biggest tool in the kit to combat excessive levels of road congestion and reduce public transport crowding.

As children slowly return to school, working from home for many may become easier, and while there is mild agreement that people would like to go to work to avoid social isolation, that feeling of social isolation may be less of a concern as people are slowly allowed to visit friends and family again. Governments will need to sit down with representatives of employer and employee organisations and look at what incentives and investment is required to make working from home a viable long-term proposition for more Australians. The survey suggests a high incidence of choosing to work from home. While it is likely that, as a function of the 4sqm social distancing regulations currently in effect, offices will need to continue to support flexible work arrangements, if not widely adopted by industry then governments might need to consider extreme response such as mandating some form of work from home arrangement where business is required to allow staff to work from home one or two days a week on a rotating basis.

4.8. Infrastructure investment and funding

Typically, infrastructure investment in transport projects is used as a stimulus measure in economic recovery efforts. However, with the present amount of disruption, authorities should think very carefully about any future infrastructure investment, particularly while post-COVID-19 behaviours remain unknown and unpredictable. Indeed, governments may wish to give some thought to pausing large infrastructure projects in the public transport space (and potentially even those like the second Sydney Airport), perhaps thinking laterally about increased infrastructure spend on a smaller scale such as investment in improved bicycle lanes and accessibility. If looking to spending on a larger scale, investment should support infrastructure that would facilitate the ability for more people to work from home or engage in flexible working hours. Perhaps somewhat controversially coming from those working in transport, there may be a need to move large scale priority funding towards increasing the provision of essential services such as health care, education, or social infrastructure. If there is one thing governments should be wary of, it would be any investment in transport infrastructure that would serve to further exacerbate the dominance of the motor vehicle in a post-COVID-19 world.

With respect to funding infrastructure investment in roads, the time might be right to revisit road pricing as a viable mechanism, particularly if the travelling public truly sees the value of significantly reduced traffic congestion (Butt, 2020). The impact of COVID-19 on toll road revenue has been significant, with Transurban reporting a 29% fall on its Sydney roads, 43% fall on its Melbourne toll road, and a 27% fall on the assets owned in Queensland (Rabe and Hatch, 2020). If there is a permanent shift to more people working at home following the COVID-19 outbreak, there would be a significantly detrimental impact on the viability of toll roads and thus road funding via this mechanism. A recent white paper by management consultancy WSP outlines the similar impact of COVID-19 on revenue for transportation, and calls for an expanding use of tolling (akin to widespread road pricing) as a backstop lost revenue and prevent the return of saturated congestion (WSP, 2020). With respect to road pricing schemes, research indications that such schemes can gain support from the general public (Harrington et al., 2001), and be devised without any cost impost to user greater than those that exist (Hensher and Bliemer, 2014).

5. Limitations and future research

5.1. Limitations of the current study

As with all studies, there are a number of trade-offs that need to be considered when balancing the need for speed of getting into field given the rapidly growing disruption, the overall length of the survey as it stood, and limited budgets given university wide spending freezes placing further cost pressures. There are likely a number of ways in which this research could be improved, but perhaps most importantly is that the data analysed herein does not have sufficient freedom to understand the working from home experience in great detail. We know that many are doing so, but as of yet we do not know how positive or negative that experience has been, nor how productive employees have been. What we do know from the data that we have collected is that in these initial stages there is likely a “two speed economy” wherein there are those who have the ability to work from home and are successfully doing so, and those who cannot.

Future research should look to examine work from home and flexible working hours in far greater depth, and in particular look to understand the likelihood of the employer supporting working from home moving forward. It should also examining working from home over the longer term. Ongoing work by the authors will seek to do this. It should also be noted that the focus of this paper was working from home, but equally a large number of educational activities were interrupted by COVID-19. There is an opportunity to look at the disruption to these activities, particularly as in some jurisdictions educational travel (especially at a tertiary level) accounts for a high percentage of transport volume.

Understanding the support and propensity to work from home continuing will be a crucial opportunity for transport policy makers not only in the current climate but also in combatting the persistence of congestion. While perhaps not at the extreme of the COVID-19 panic, a small reduction in daily travel by a small and sustained increase in working from home will have significant benefits in terms of reduced traffic congestion and less crowding on public transport. While some may argue that a survey comprised of online panel members may overstate the ability to work from home, we would argue that it would not take a large reduction in traffic to remove pressure on transport bottlenecks and increase the overall efficiency of the network. Given that BITRE (2015) claim a loss of $30billion plus in travel time benefits due to congestion, understanding work from home and gaining insight into how to sustain increased levels will potentially return large societal gains.

Future waves of this study will also seek to understand household characteristics in more detail, such as car and bicycle ownership, the availability of transport modes with respect to daily travel and a more nuanced examination of the impact of COVID-19 on employment as well as potential uptake of support programs such as JobSeeker and JobKeeper. Future research should also examine freight transport in more detail than completed herein, in particular the response of the retail and food sector to securing supply whilst under unforeseen demand pressures. Additionally, there is scope to examine the preparedness of the parcel and last mile delivery services, which experienced significant delays resulting in well publicised dissatisfaction (e.g. Stanley and Wong, 2020).

5.2. Future research directions

While the disruption to travel is widespread, the unfortunate reality is that a large part of that disruption is because of changes to work and employment. More than two-thirds of household's surveyed (70%) have been impacted, or know of someone whose availability of work was impacted, by the government regulations introduced to combat the spread of COVID-19. The impact can be seen most dramatically in the findings that the number of people working five days a week has fallen from 57% to 39%; and 27% of the sample who were working at least one day prior to COVID-19 are no longer working. It is clear that there is great need for research in to the impact of COVID-19 on work, not only because of the demand for transport that is derived from work and other activities.

Interestingly, there are important implications for the future of work that may emerge from the COVID-19 experience. Our preliminary evidence is that those who have experienced the largest disruption to the availability or safety of their work have been those involved in human facing industries: personal service and retail; restaurants, cafés and bars; the arts and creativity. These industries have been long argued to be the bastion of future employment, where interpersonal and creative skills will be central to the future of work, as they are jobs which are the hardest to automate. We have now flirted with the concept of a universal basic income, with the lifting of the unemployment benefit (JobSeeker) and the government subsidisation of wages (JobKeeper) (Australian Government 2020).

To conclude this section with a short number of interesting research directions that may arise from the disruption cause by COVID-19:

- •

In the longer term, there may be architectural and urban design issues that will arise from the different way in which work is done; office spaces previously designed for hot-desking and open plan face a redesign, and homes might also need to be rethought with a dedicated space for work. Ultimately, this may have impact on the need to be close to places of work, and as that evaporates there may even be a move towards less dense living, reversing the densification seen over the course of the last decade. Research should examine any such changes, or lack thereof.

- •

Perhaps authorities can leverage the current enjoyment of better amenity in terms of congestion and resultant pollution, combined with significant improvement to health as a result of less tailpipe emissions, to encourage lower levels of car use to be ongoing. Should demand for private car travel return in a significant way, it may also be worthwhile to accelerate the adoption of electric vehicles as a means of reducing tail-pipe pollution. It will be interesting to see if the COVID-19 disruption has any impact on potential growth of alternatively fuelled vehicles.

- •

There is a high degree of uniformity in the behavioural response of Australian's to COVID-19 measures. It is possible that the behaviour is motivated either altruistically through the recognition that COVID-19 presented a serious threat to the health of someone known to the respondent, or the egoistic motivation of the risk posed by COVID-19 to the economy. To our mind, this is an interesting social phenomena that is worthy of greater research.

6. Conclusion

This paper presents the preliminary findings from a survey conducted in the middle of March 2020, at what was the height of first (and hopefully only) outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Importantly, data was collected at the height of the COVID-19 restrictions (assuming there is no second wave of infections), which will provide a very useful reference position as we come out of Covid-19 restrictions and collect subsequent waves of date to identify what changes in travel behaviour in particular might continue at least in the short run if not longer. We use our results to provide policy suggestions across seven separate domains: food and freight; aviation; public transport; motor vehicle and road use; active transport; flexible working; and infrastructure investment.

The survey covered a large number of behaviours and attitudes, and in doing so we are able to provide a thorough depiction of the mood of the nation toward the threat of COVID-19, the response to the pandemic, and the disruption to travel and activities experienced. Our key finding is Australians have followed the urgings of National Cabinet and all levels of government, to limit travel and social contact, which has thus far resulted in a “flattening of the curve”. In the short-term, our results point towards a significant need to think about public transport policy (indeed policy on all shared modes) in time of concern around hygiene and limitations on capacity die to social distancing. In the longer term, our research highlights the need to be wary about any policy or investment that would further entrench the motor vehicle as the predominant form of transport.

Finally, we urge policy makers and researchers alike to look more fully at the role of working from home in the “new normal” that follows COVID-19. It is clear that there is a dyadic impact of COVID-19 restrictions on those who can work from home and those who cannot, as well as the impediments and experiences of working from home by those who have been able to do so. However, despite the ills of COVID-19, we have an opportunity not to be foregone by industry and government. Increased levels of working from home may result in being a policy lever that can most significantly reduce congestion and crowding, potentially to benefit climate change, wellbeing and infrastructure priority funding, enabling a greater amount of funding directed to essential services such as health services and care support.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Matthew J. Beck: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. David A. Hensher: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous referees and editor Xiaowen Fu for their timely and insightful comments, which have improved this paper.

Footnotes

The amount varied by State, with NSW introducing the fines outlined in the text.

In discussing the results of tests based on individual and household characteristics, all testing is performed at a 5% level of significance. The authors can provide the outputs of any test upon request.

https://ivtmobis.ethz.ch/mobis/covid19.Using MOBIS and GPS tracking, they found ~50% reduction in tracked trips, more or less mirroring the Australian findings in this paper.

“While it is the case that overall goodness of fit is low (outside a typical logit range l fit between 0.2 and 0.4 (Domencich and McFadden, 1975, page 124), it should be noted that this is after allowing for the constant where we are assuming the base is known shares. Importantly however, many well respected modellers have argued that there is important information associated with statistically significant variables regardless of what overall fit is obtained. Hence the statistical significance of the reported variable has behavioural merit.”

This concern also applies to trains and ride share, although they were not found to be statistically significant. We suspect this is because bus is the dominant mode in most cities and outside of the major metropolitan areas.

The R2 value could be considered relatively low, but it should be noted that this model is produced at a time where government restrictions (a dominating explanatory variable) were implemented giving people little choice but to reduce their travel, irrespective of attitude or characteristics. This model is, in effect, looking at changes that can be made at the margins of already reduced travel.

The Federal government introduced free tele-health to enable appointment with a GP to be made from home.

The perceived appropriateness of state government responses will need to be examined on a state-by-state basis, particularly to see if there is any impact of the Ruby Princess disembarkation in NSW. NSW instigated an inquiry in mid-April which is likely to run for at least 6 months.

As of May 6, the supermarkets have advised that there is no shortage of stock, and in some cases they overstocked since people have started hoarding, with soup the most popular purchase.

Skedgo has recently developed this capability in their TripGo App.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.07.001.

Contributor Information

Matthew J. Beck, Email: Matthew.Beck@sydney.edu.au.

David A. Hensher, Email: David.Hensher@sydney.edu.au.

Policy recommendation overview

General mood was one of support of the actions taken by Federal and State governments, and the response of business to the COVID-19 impact. We see a widespread suppression of travel demand for all trip purposes across all modes, and a sizeable shift to working from home by those who can. When easing restrictions, public transport will face the largest hurdles in regaining confidence.

Overviewing key recommendations

Retail and food logistics will need to examine distribution processes and should a second wave or different pandemic be ready to implement demand control measures to avert panic buying.

The aviation sector will likely need to restart with a heavy focus on domestic travel, appealing to the need to support rural and regional tourism, perhaps working to create appealing package offers for travellers.

Public transport will need to take overt measures to restore confidence in the cleanliness of the mode. Demonstrable signs of regular and thorough cleaning, staff working to move platforms and stops quickly and efficiently. Perhaps better use of time of day charging to suppress peak travel. At an extreme, masks may be required to ride if it increases traveller sentiment.

The dominance of the car is further enforced in the context of biosecurity concerns. There may need to be regulatory oversight to ensure no price gouging in inner city parking. Some flexibility may be required around vehicles using bus lanes in the short-term. There may be a need to ration road space in a worst-case scenario.

Active transport is a viable option for short inner-city trips. If possible, this mode should be encouraged more so than the car. Relaxations to footpath regulations for bicycles should be considered, pop up bicycle lanes should be encouraged. Easing restrictions on motorised scooters might also be an option.

Infrastructure investment should be carefully considered. Some projects might need to be paused and those that would only further entrench the motor vehicle as the dominant form of transport should be treated with great caution. Toll road revenues have been seriously impacted and now might be the time to revisit a wider road pricing scheme.

Flexible working arrangements are perhaps the biggest policy lever available to governments. All jurisdictions should so whatever possible to facilitate the continuance of working from home now only in the short term, but also longer term. Any investment that increases the ability or propensity for people to work from home should be considered as an impactful transport investment.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- ABARES . 2020. Australian Bureau of agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences.https://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/publications/insights/australian-food-security-and-COVID-19 accessed 15/06/20. [Google Scholar]

- ABS . 2020. Australian Bureau of Statistics.https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4940.0Main+Features11-6%20Apr%202020?OpenDocument accessed 03/05/20. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government 2020. https://treasury.gov.au/coronavirus/jobkeeper (April)

- Australian Department of Health. 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/daily-number-of-reported-COVID-19-cases-in-australia accessed 03/05/20. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Infrastructure . Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development; Canberra: 2015. Transport and Regional Economics (BITRE) Information Sheet 74. [Google Scholar]

- Butt C. How coronavirus turned peak hour into a Sunday morning drive. 2020. https://www.smh.com.au/national/how-coronavirus-turned-peak-hour-into-a-sunday-morning-drive-20200402-p54gem.html accessed 16/06/20.

- Chang S., Harding H., Zachreson C., Cliff O., Prokopenko M. Centre for Complex Systems, Faculty of Engineering, University of Sydney; Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia: 2020. Modelling Transmission and Control of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Australia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domencich T.A., McFadden D. North-Holland; Amsterdam: 1975. Urban Travel Demand: A Behavioral Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Google Community Mobility Report. 2020. https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/ accessed 03/05/20. [Google Scholar]

- Greene W.H., Hensher D.A. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, April: 2010. Modeling Ordered Choices: A Primer and Recent Developments. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington W., Krupnick A.J., Alberini A. Overcoming public aversion to congestion pricing. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 2001;35(2):87–105. doi: 10.1016/S0965-8564(99)00048-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]