Abstract

Theoretically, in the tourism context this study introduced a new concept of non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) for influenza, and tested the impact of NPI on the behavioral intention of potential international tourists. This study also extended the model of goal-directed behavior (MGB) by incorporating the new concepts of NPI, and the perception of 2009 H1N1. The model found that desire, perceived behavioral control, frequency of past behavior, and non-pharmaceutical interventions predicted tourists’ intention but perceptions of 2009 H1N1 had nil effect on desire and intention. Personal non-pharmaceutical interventions were theorized as adaptive behavior of tourists intending to travel during a pandemic which should be supported by tourism operators on a system-wide basis. Practically, this study dealt with the issue of influenza 2009 H1N1 with the study findings and implications providing government agencies, tourism marketers, policy-makers, transport systems, and hospitality services with important suggestions for NPI and international tourism during pandemics.

Keywords: 2009 H1N1, Non-pharmaceutical intervention, Model of goal-directed behavior, Travel intention

1. Introduction

In June 2009 the United Nations World Tourism Organization identified the outbreak of a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus, later known as 2009 H1N1, as intensifying the harsh effect of the global economic crisis on international tourism, however, this was varying by region (UNWTO, 2009a, p. 1). All regions, excepting Africa (+3%) and South America (+0.2%) seeing declines in tourism demand. By October, the UNWTO’s panel of experts was predicting that after fuel costs, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and uncertain currency exchanges rates would have secondary negative impacts on long-haul travel in 2010 (UNWTO, 2009b, p. 6). Then, in January 2010, 2009 H1N1 was classified as a downside risk with less overall impact than expected but which could emerge as a threat to international tourism recovery and growth (UNWTO, 2010, p. 7). Looking back at international tourism arrivals in 2009, which were estimated as declining by 4%, the economic crisis, currency variations, and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic were all factors depressing outbound travel. With the pandemic impacting markets in Northeast Asia and the Americas particularly (UNWTO, 2010, p. 14), the 2009 H1N1 pandemic was a significant negative factor in an “exceptionally challenging” year for international tourism.

Yet, little is known about how potential outbound tourists behave when they are considering overseas travel during an Influenza pandemic. Understanding their behavior would help government agencies, tourism marketers, transport systems, and hospitality services cope with a crisis more effectively. This study classified the perceived risk for 2009 H1N1, a novel influenza virus that emerged in Mexico, as an obstacle which could discourage tourists from visiting other countries. For instance, if tourists who are planning international travel perceive risks from 2009 H1N1, such as suffering illness while abroad, they could postpone or cancel their plans (Reisinger & Mavondo, 2005). We theorized that in a pandemic, potential tourists would consider voluntary personal non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) which could decrease their risk of 2009 H1N1 infection while traveling. Tourists may choose NPI because of the delay in the production of effective antiviral drugs and vaccines, or because of limited vaccine availability in their country (Chaturvedi, 2009). Personal NPI include getting better knowledge of the disease and pandemic; improving personal hygiene practices while traveling; using social distancing to avoid suspect people or places; and monitoring personal health before and after the trip (Nicholl, 2006).

Comprehending and predicting travelers’ behavior is a main issue for tourism marketers, particularly when a certain obstacle for traveling like an Influenza pandemic exists. The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) are frequently used in previous studies for understanding travelers’ intentions or behavior. However, these theories have limitations. They do not contain the influence of past behavior which may affect intention and behavior (Leone, Perugini, & Ercolani, 1999) and they focus on the cognitive variables without considering affective variables associated with behavior (Conner & Armitage, 1998). So, the present study employed the model of goal-directed behavior (MGB), which considers motivational process, affective process, and past behavior, to better predict potential travelers’ decision-making processes. According to Perugini and Bagozzi (2001) theory broadening and deepening of this theory is necessary for improving predictions of human behavior in differing contexts. Hence, this research extended the MGB by including perceptions and NPI for 2009 H1N1 that were meaningful in explaining human behavior better.

Using a sample of Korean potential international tourists we explain tourists’ decision-making procedures by applying the MGB theory and a model that includes perceptions of the disease 2009 H1N1 and the NPI which respond to that disease. The study had four aims. First, examining potential travelers’ decision-making processes when the risk of 2009 H1N1 infection discourages traveling abroad, by developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior (EMGB) explaining international travel intent that includes perceptions of 2009 H1N1 and NPI in the MGB framework. Second, verifying the superior predictive ability of the EMGB compared with the TRA and TPB. Three, examining the perceptions of the 2009 H1N1 virus and the NPI for the virus among a sample of Korean potential overseas travelers and the role of these perceptions in a proposed theoretical framework. Four, providing government agencies, tourism marketers, transport systems, and hospitality services with practical suggestions for NPI which could mitigate pandemics and benefit the public and tourism businesses.

2. Background to the study

2.1. Pandemics and tourism: historical context and global consequences

The worldwide caution surrounding the 2009 H1N1 outbreak stems from international apprehension of another global catastrophe like the 1918 ‘Spanish Flu’ influenza pandemic or of an economic shock like the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome corona virus (SARS) epidemic. During March 2009, an unfamiliar influenza-like illness appeared in the Mexico (World Health Organization [WHO], 2009a). In April under international health protocols the Mexican government reported this to the Pan-American Health Organization as an outbreak of a novel influenza type virus (Neumann et al., 2009, World Health Organization, 2009a). Then, the United States Centers for Disease Control identified the virus as a new strain of Influenza A H1N1 (Jeeninga, de Jong, & Berkhout, 2009) now known as 2009 H1N1. Within six months, as the number of people infected by 2009 H1N1 rapidly increased globally, the WHO quickly increased the pandemic alert for 2009 H1N1 to the high phase six level (WHO, 2009b).

Symptoms of 2009 H1N1, including cough, runny or stuffy nose, sore throat, and high fever are similar to seasonal influenzas as are the inter-person infection paths. Scientists worry about it being a critical virus which could mutate into a virulent deadly form (World Health Organization, 2009a, Jeeninga et al., 2009) like the Influenza A H1N1 that ravaged the globe on the heels of the First World War. That lethal strain of influenza, known as the ‘Spanish Flu’, killed up to 100 million people between 1918 and 1920, according to later estimates (Kolata, 2001, p. 7). Appearing in a mild form causing flu-like symptoms of coughs and high fever for three days with mild mortality, then, reappearing within six months as a deadly mutation with a high mortality level it spread around the world killing millions rapidly. In the steam transport era the killer disease circled the globe in a year (Kolata, 2001).

In the air transport era, which yearly moves more than two billion passengers around a network of 35,000 commercial airline connections among commercial airports in close to 3500 cities, a lethal disease can spread around the planet rapidly (St. Michael’s Hospital, 2009, p. 17). For example, SARS, called the first emerging disease of the age of globalization (Omi, 2006, p. ix), moved about the planet on airline jets, appearing in China’s Guangdong Province during November 2002 and arriving in Toronto, Canada, on 23 November 2003. A Canadian tourist, who unknowingly contracted the illness while staying in a Hong Kong hotel, flew home while authorities were trying to identify the novel virus (Varia et al., 2003). The Toronto SARS outbreak caused 44 deaths, hundreds of infections, quarantine for thousands of citizens, billions of dollars in lost production, and a billion dollars in outbreak control measures (St. Michael’s Hospital, 2009).

Criticisms of overreaction, directed in retrospect, at the WHO, various national governments, and the media about the handling of the 2003 SARS outbreak shows the sensitivity surrounding international cooperation for pandemic disease control (Mason et al., 2005, McKercher and Chon, 2004). Reactions to SARS included WHO travel warnings for particular geographical regions, extensive media coverage of the outbreak, travel advisories against Asian countries, and the curtailing tourist’s civil rights at some borders and destinations. In the following panic three million people lost their tourism industry jobs, a $20 billion gross domestic product (GDP) decline occurred in China, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Vietnam, and tourism flows across Asia lessened by 70% (McKercher & Chon, 2004). The global management of emerging infectious diseases occurs in this complex environment of fear of an unstoppable killer virus, rapid mass international travel, and the reluctance to cause national or international economic damage through inappropriate alerts and warnings.

2.2. 2009 H1N1: pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions

National management choices for constraining an emerging influenza virus include pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions (Oshitani, 2006, Rizzo and degli Atti, 2008). Pharmaceutical choices include using antiviral drugs and fabricating new vaccines. Several groups of antiviral drugs are useful during an influenza pandemic’s early stage. However, drug resistance limits the efficacy of the cheaper and more obtainable group of M2 inhibitors, whereas difficulties of distribution, dosage, and supply limit the usefulness of the more expensive group of neuraminidase inhibitors. Also, three parameters govern the benefits of pandemic influenza vaccines: the four to six months to fabricate a new vaccine, the possibility of several doses being needed, and limited production capacity (Finkelstein, Prakash, Nigmatulina, Klaiman, & Larson, 2009, p. 6; Oshitani, 2006, p. 168). With these constraints on the efficacy and availability of pharmaceutical interventions during an influenza pandemic’s early stage, NPI are essential for slowing the outbreak (Aledort, Lurie, Wasserman, & Bozzette, 2007).

These NPI comprise administrative control measures and non-mandatory personal protective measures (Raude & Setbon, 2009, p. 339). Administrative NPI measures include isolating infected patients, quarantining individuals in contact with the infection, hospital infection control, and border control whereas personal NPI measures include social distancing, and personal hygiene protection (Oshitani, 2006, p. 169). Social distancing by closing schools, calling off public events, reducing access to public transport, and working from home during an outbreak diminishes the chance for person-to-person infection. Hygiene action by washing hands, wearing masks, and techniques for containing coughing and sneezing restrict disease transmission (Finkelstein et al., 2009). During the SARS outbreak, the administrative NPI of contact tracing, quarantine, and isolation were important in restricting the spread of the virus (Omi, 2006). A supplementary NPI was the Internet’s role in keeping the global public up-to-date, and linking the medical experts seeking to identify the novel virus (Omi, 2006).

At the end of 2009, the impact of 2009 H1N1 pandemic on tourism and hospitality remains unclear as declines in travel sales occurred simultaneously with the worldwide economic recession (Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). As May 2009 ended, a high correlation appeared between H1N1 importations and 16 out of the 20 countries with the uppermost quantity of air passenger arrivals from Mexico. More generally, if a country received more than 1400 air passenger arrivals from Mexico the risk of H1N1 importation increased markedly (Khan et al., 2009). During the 2009 Southern Hemisphere winter, however, fear of the disease probably caused short-term and or localized social and economic effects and a temporary decline in tourism in Australia, Argentina, Chile, New Zealand, and Uruguay (Department of Health and Human Services, 2009, p. 9). The five countries each used community mitigation measures in response to the disease including using antiviral drugs and NPI measures.

The NPI measures were administrative controls like closing schools, banning public gatherings, and quarantining ill patients. Before the disease appeared in their territories Australia and Chile used thermal screening to detect inbound tourists with raised surface temperatures and then switched from this containment phase to a mitigation phase when the disease appeared in their populations. Some flights were canceled between Argentina and Mexico; questionnaires and information pamphlets were used at the U.S. and Mexico border; and New Zealand screened passengers from countries of concern (Department of Health and Human Services, 2009, p. 7). The 2009 H1N1 outbreak illustrates the complexity of implementing NPI administrative controls on a global basis. For example, 2.35 million air tourists from Mexico arrived in 1018 cities in 164 countries during March and April 2008, with a similar pattern estimated during the same months in 2009 when the novel 2009 H1N1 virus emerged (Khan et al., 2009).

There are several complications in detecting and discouraging travel by infected passengers who may be the vector by which a virulent influenza virus moves across the global airline network (St. Michael’s Hospital, 2009, p. 111). First, the disease incubation period is longer than the typical journey period. Second, passengers who experience symptoms may not admit their condition for fear of disrupting their travel arrangements. Third, fast reliable screening and diagnostic techniques for infectious diseases among airline passengers while they are in the airline network are not commonly available. Therefore, passive controls at national borders have limited effectiveness at halting the arrival or departure of an influenza-like infectious disease and the near symmetry between international airport-pairs means shared risk of export and import of ill passengers. Besides, to impede an outbreak by several weeks or more would need a 99% effectiveness of border controls and internal travel checks (Ferguson et al., 2006).

The 2009 H1N1 outbreak from Mexico shows how rapidly and broadly a disease spreads while the authorities scrambled to identify the new virus. Therefore, improving disease recognition, scrutiny, management, and education which limit person-to-person disease transfers in aircraft and at airports, requires cooperation beyond national borders (St. Michael’s Hospital, 2009, p. 111). The complexity of rapid international air transport; the efficacy and availability of antiviral drugs and vaccines; and the difficulty of NPI like border controls, mean that stopping a pandemic is an evolving global challenge. A pandemic affects tourism-related industries negatively because potential tourists experience increases in perceived risk and anxiety due to inadequate information about the origins, prevention, and treatments for the disease (Wu, Law, & Jiang, 2010). So, when a pandemic alert is active the intentions of tourists to travel internationally, their perception of the disease, and personal protective NPI measures for the disease need further investigation.

2.3. Theories of behavior and hypothetical relationships

The TRA and TPB are considered as a representative social psychological theory in the understanding of specific human behavior (Zint, 2002). To improve the usefulness of the TRA and TPB, Perugini and Bagozzi (2001) proposed the model of MGB which includes all original variables in the TPB but redefines their role as indirectly affecting behavioral intention through desire. They also claimed that motivational, affective, and habitual processes should be included in the social psychological model in order to better comprehend human behavior. In terms of motivational process, desire was suggested as a critical factor in explaining decision formation (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2001). With regard to affective process, anticipated affective reactions to a specific behavior were recommended as an imperative variable in decision-making processes (Conner & Armitage, 1998). In terms of habitual process, past behavior was suggested as a significant determinant of human decisions (Aarts et al., 1998, Bentler and Speckart, 1981, Ouellette and Wood, 1998). So, to better understand specific human behavior the MGB incorporates desire, positive and negative anticipated emotions, and past behaviors as well as the original variables of the TPB. Therefore, the MGB incorporates desire, positive and negative anticipated emotions, and past behaviors besides the original variables of the TPB.

A revision of existing social psychological theories is necessary to improve predictions of human behavior in unique contexts (Ajzen, 1991). Perugini and Bagozzi (2001) describe this process of including new constructs as theory broadening and deepening. Taylor (2007) showed that the MGB can explain variance of intention and behavior in a particular context by including extra variables as an extended MGB.

In order to understand international tourists’ decision-making process during the emerging 2009 H1N1 pandemic, this study added two more constructs (the perception of 2009 H1N1 pandemic and the NPI for 2009 H1N1 pandemic) as an EMGB besides the original framework of MGB.

2.4. Attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and desire

Researchers agree that attitude toward a behavior exerts a positive influence on a person’s intention to perform the behavior (Baker et al., 2007, Cheng et al., 2006). The TPB asserts that attitude toward a behavior strengthens a person’s intention to perform it, however, the MGB redefines attitude as affecting intention indirectly through desire. So, attitude toward a behavior in the MGB affects intention indirectly through desire (Leone et al., 2004, Perugini and Bagozzi, 2001, Prestwich et al., 2008). As salient referents influence personal decision-making and behavior (Bearden and Etzel, 1982, Cheng et al., 2006) a person considers complying with other people’s opinions when determining if they should undertake a behavior. This subjective norm is the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior (Ajzen, 1991). In the MGB this would not directly fortify a person’s behavioral intention but effects behavioral intention indirectly through desire (Leone et al., 2004, Perugini and Bagozzi, 2001, Prestwich et al., 2008).

The PBC, which refers to individual confidence to carry out a behavior, is an important factor in forming intention (Ajzen, 1991, Ajzen and Madden, 1986) and affecting decision-making formation in the TPB (Ajzen, 1991, Ajzen and Madden, 1986, Conner and Abraham, 2001, Taylor and Todd, 1995). In the MGB it reinforces desire, behavioral intention, and actual behavior (Carrus et al., 2008, Perugini and Bagozzi, 2001, Prestwich et al., 2008). Using the literature, three antecedent variables for attitude, subjective norm, and PBC were hypothesized to have a positive effect on the desire for overseas travel. These were: H1 – Attitude has a positive influence on desire; H2 – Subjective norm has a positive influence on desire; and H3 – PBC has a positive influence on desire. Also, it was hypothesized that PBC would positively affect the intention for overseas travel: H4 – PBC has a positive influence on behavioral intention.

2.5. Relationships between anticipated emotions and desire

With regard to affective influence on a decision-making process, anticipated affective reaction to performing a behavior would be an important determinant of intention (van der Pligt and De Vries, 1998, Triandis, 1977). In uncertain situations people may have forward-looking emotions toward future behaviors. Gleicher et al. (1995) identified these anticipated counterfactuals as prefactuals which can affect intention and behavior implying that expected emotions of goal success or failure can be included in the MGB. Perugini and Bagozzi (2001) showed that both positive and negative anticipated emotions have a critical role in forming desire. It was hypothesized that positive and negative emotions significantly affect desire as follows: H5 – positive anticipated emotion has a positive effect on desire; and, H6 – negative anticipated emotion has a negative effect on desire.

2.6. Relationship between past behavior, desire, and intention

The influence of past behavior was found to have an effect on individual intention in several attitude and behavior studies (Bagozzi & Warshaw, 1992). Specifically, past behavior is often integrated into a theoretical framework that explains an individual’s decision-making process (Conner & Armitage, 1998). Past behavior is regarded as a proxy of habit, implying that it influences desire and intention (Bagozzi and Warshaw, 1992, Bentler and Speckart, 1981, Fredricks and Dossett, 1983). In the MGB, it was theorized that past behavior influenced desire, intention, and actual behavior (Conner and Armitage, 1998, Ouellette and Wood, 1998). The final dependent variable in this study was behavioral intention, not actual behavior. So, this study hypothesized that past behavior affects desire and intention as follows: H7 – past behavior has a positive effect on desire; and H8 – past behavior has a positive effect on intention.

2.7. Relationships between desire, intention, 2009 H1N1, and non-pharmaceutical interventions

Bagozzi (1992) claims that the TPB omits desire as a key factor, a motivation-based construct leading to intention where desire relates closely to intention, so in the MGB desire is a proximal cause of intention. Whereas the MGB considers other antecedents as distant causes which desire mediates before they affect intention (Bagozzi, 1992). Leone et al. (1999) claimed that the TPB did not entail motivational commitment but that the intention to undertake a specific behavior requires desire (Bagozzi, 1992, Leone et al., 1999). In the MGB desire is regarded as the most proximal determinant of intention (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2001). So, it was hypothesized that desire has a positive effect on intention to travel overseas, whereas other antecedents (e.g., attitude, subjective norm, positive anticipated emotion, negative anticipated emotion, and frequency of past behavior) in the MGB affect intention through desire: H9 – desire has a positive effect on intention.

Perception refers to an individual’s knowledge, information, and experiences which are responsive to their cognition of objects, behaviors, and events (Anderson, 2004). People form their attitudes, interests, and opinions through the perceptions which they acquire in their day-to-day lives (Oliver, 1997). Some studies of perceived risks support the possible relationships between perception of influenza, desire, and intention (Aro et al., 2009, Brug et al., 2004, Reisinger and Mavondo, 2005, Sonmez and Graefe, 1998, Wu et al., 2010). Sonmez and Graefe (1998) stated that perceived risks play a critical role in altering a tourist’s decision-making process. Reisinger and Mavondo (2005) claimed that risks perceived by tourists negatively affect their travel intention so they are likely to choose between keeping their travel plans, changing their destination choice, altering their travel behavior, or getting pertinent information. Thus, an individual’s perception of 2009 H1N1 may affect their decision-making process as an international tourist.

Therefore, in spite of the influenza, some tourists who desire and intend to travel overseas will prepare health procedures in conjunction with their trip (Reisinger & Mavondo, 2005). Without the pharmaceutical protection of a vaccine they may voluntarily implement personal NPI prior to, during, and following their trip to mitigate their perceptions of risk (Aledort et al., 2007, Aro et al., 2009, Brug et al., 2004). These include gaining better knowledge about the disease and the pandemic, actions for improving their personal hygiene while traveling, and decreasing infection possibilities by social distancing from suspect people and places. The study posited that perceptions of 2009 H1N1 have a direct or indirect effect on tourists’ desire and intention to travel through NPI to avoid H1N1 infection as follows. H10 – perception of 2009 H1N1 has a negative influence on desire; H11 – perception of 2009 H1N1 has a positive effect on non-pharmaceutical interventions; H12 – perception of 2009 H1N1 has a negative effect on intention; and H13 – non-pharmaceutical interventions have a positive effect on intention.

3. Methods

3.1. Measures and operational definition of variables

A preliminary list of measurement items was generated after an extensive review of literature concerning the behavior of international tourists, theories of human behavior including TRA, TPB, and MGB, information on Influenza A H1N1, and prevention measures for influenza diseases (Ajzen, 1985, Ajzen, 1991, Ajzen and Madden, 1986, Bagozzi et al., 1998, Bentler and Speckart, 1981, Brug et al., 2004, Carrus et al., 2008, Lam and Hsu, 2004, Lam and Hsu, 2006, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, 2009a, Ministry for Health, 2009b, Oh and Hsu, 2001, Perugini and Bagozzi, 2001, Reisinger and Mavondo, 2005, Sonmez and Graefe, 1998, UNWTO, 2009c, World Health Organization, 2009c). Then to ensure the questionaire’s understandability tourism scholars and travel industry managers were asked to assess the items of measurements and a pretest was also conducted with 20 people who experienced an overseas trip during the past three years. Through these processes items that seemed ambiguous were reworded for clarity.

The subjects’ attitude toward overseas travel was operationalized with six items (see Appendix) as suggested by previous research (Ajzen and Madden, 1986, Bagozzi et al., 1998, Lam and Hsu, 2004, Lam and Hsu, 2006, Oh and Hsu, 2001). The subjective norm to travel internationally was operationalized with four items (see Appendix) as suggested by previous research (Ajzen, 1991, Perugini and Bagozzi, 2001, Oh and Hsu, 2001). The perceived behavioral control was operationalized with four items (Appendix) as suggested by previous research (Ajzen, 1991, Lam and Hsu, 2006). The perception of Influenza A (H1N1) was operationalized with four items (Appendix) as suggested by previous research (Reisinger and Mavondo, 2005, Sonmez and Graefe, 1998). The non-pharmaceutical interventions for Influenza A (H1N1) were operationalized with seven items. These items were derived from the codes and precautions of UNWTO, WHO, and MIHWFA to prevent from catching Influenza A (H1N1) (Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, 2009a, Ministry for Health, 2009b, UNWTO, 2009c, World Health Organization, 2009c). Three of these items included actions to improve knowledge of the disease (Appendix). Three items included actions about personal hygiene and health. And one item included action on social distancing. Desire was operationalized with four items (Appendix) as suggested by previous research (Carrus et al., 2008, Perugini and Bagozzi, 2001). Positive (4 items) and negative (4 items) anticipated emotions (Appendix) were operationalized with eight items as suggested by previous research (Carrus et al., 2008, Perugini and Bagozzi, 2001, Prestwich et al., 2008). The variables of attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, perception of Influenza, and NPI were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). However, positive and negative emotions were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from not at all (1) to very much (7). The frequency of past behavior was assessed with a single item as suggested by previous research (Bentler and Speckart, 1981, Oh and Hsu, 2001), “How many times have you traveled internationally in the past 12 months?”

3.2. Data collection and analysis

With the development of Internet some researchers in hospitality and tourism fields use online surveys to reach broader populations of interest efficiently (Han et al., 2009, Kim and Ok, 2009). This study used data collected by the top ranking Korean Internet survey firm that utilizes a nationwide panel of 490,000 online respondents from which representative samples are selected. Their standard procedures use Korean resident registration numbers matched against personal passwords for verifying the identity of panelists included in each sample. They are selected as best-fit participants by response to a sampling questionnaire and rejected during the survey if they complete their questionnaire too rapidly (Embrain, 2009). The study data were collected during July 2009, when the 2009 H1N1 outbreak was being covered by international and national media in Korea.

The Internet survey firm distributed questionaires to 990 potential tourists chosen randomly. From these, by using a screening question, we selected those with at least one overseas trip during the past three years. By this procedure 400 questionnaires were collected (40.4%) and after excluding three questionnaires as outliers 397 were coded for analysis. Collected data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (2001) and EQS –Structural Equation Modeling Software (Bentler & Wu, 1995). As a first step in the evaluation of the measurement model, exploratory factor analysis identified the structure of factors and systematically measured variables in underlying constructs. This lessened multicollinearity or error variance correlations among indicators (Bollen, 1989, Yoon and Uysal, 2005). The structural equation modeling used a two-step hybrid method by specifying a measurement model in the confirmatory factor analysis and testing a latent structural model developed from the measurement model (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988, Hatcher, 1994, Kline, 2005).

4. Results

4.1. Profile of respondents and measurement model

The proportion of male and female respondents was 57.4% and 42.6% respectively, most respondents (73.8%) were aged 20–49 years, and university graduates predominated (64.4%). Respondents with an international travel plan (78.1%) preferred package tours (55.9%), liked traveling internationally with family (47.6%) or friends (24.4%), and most (79.3%) indicated that vacationing was their main reason for overseas travel. The preferred destinations included East Asia (26.2%), Europe (23.9%), Japan (17.4%), China/Hong Kong/Macao (11.8%), and Australia or New Zealand (9.8%). The model was analyzed using EQS 6.1 to establish the degree of reliability and validity of the confirmatory factor analysis which was composed of 42 observed variables and 9 latent variables. Since Mardia’s standardized coefficient (76.5) is greater than the criterion of 0.5 (Byrne, 2006) it is considered the data are multivariate non-normally distributed, so maximum likelihood robust estimation associated with the Satorra–Bentler was used (Byrne, 1994a, Byrne, 1994b).

This approach for non-normality in multivariate data makes corrections to the standard errors, Chi-square, and other fit indexes (Bentler and Wu, 1995, Byrne, 1994a). Table 1 shows the good fit to the data (RMSEA = 0.029, CFI = 0.973, NFI = 0.899) and enough internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.853 to 0.961 (Nunnally, 1978). Convergent and discriminant validity were examined to judge construct validity. All factor loadings were greater than the minimum criterion of 0.5, with significant associated t-values and all average variance extracted and composite reliability values for the multi-item scales exceeding the minimum criterion of 0.7 and 0.5 respectively (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2006). Thus, convergent validity was fully supported. Also, the average variance value extracted for each construct was greater than the squared correlation coefficient for corresponding inter-constructs. These results confirmed the sufficient level of discriminant validity of the measurement model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Table 1.

Results of measurement model.

| Constructs | Correlations among latent constructs (squared)a and reliabilities of constructs | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | SN | PBC | PAE | NAE | PI | DE | NPI | BI | CRc | AVEd | |

| Attitude (AT) | 1.000 | 0.944 | 0.739 | ||||||||

| Subjective norm (SN) | 0.491 (0.241) | 1.000 | 0.961 | 0.861 | |||||||

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) | 0.255 (0.065) | 0.396 (0.157) | 1.000 | 0.841 | 0.571 | ||||||

| Positive anticipated emotion (PAE) | 0.751 (0.564) | 0.510 (0.260) | 0.201 (0.040) | 1.000 | 0.916 | 0.732 | |||||

| Negative anticipated emotion (NAE) | 0.278 (0.077) | 0.309 (0.095) | 0.188 (0.035) | 0.504 (0.254) | 1.000 | 0.867 | 0.620 | ||||

| Perception of Influenza (PI) | 0.042 (0.002) | 0.113 (0.013) | −0.019 (0.000) | 0.090 (0.008) | 0.036 (0.001) | 1.000 | 0.877 | 0.641 | |||

| Desire (DE) | 0.700 (0.490) | 0.579 (0.335) | 0.251 (0.063) | 0.792 (0.627) | 0.496 (0.246) | 0.034 (0.001) | 1.000 | 0.917 | 0.734 | ||

| Non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) | 0.208 (0.043) | 0.194 (0.038) | 0.133 (0.018) | 0.235 (0.055) | 0.089 (0.008) | 0.584 (0.341) | 0.209 (0.044) | 1.000 | 0.885 | 0.527 | |

| Behavioral intention (BI) | 0.605 (0.366) | 0.656 (0.430) | 0.461 (0.213) | 0.692 (0.479) | 0.428 (0.183) | 0.083 (0.007) | 0.842 (0.709)b | 0.283 (0.080) | 1.000 | 0.938 | 0.790 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.942 | 0.961 | 0.853 | 0.914 | 0.876 | 0.882 | 0.914 | 0.904 | 0.933 | ||

| S−B χ2 = 981.532, df = 736, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.029, CFI = 0.973, NFI = 0.899 | |||||||||||

Correlation coefficients are estimates using a EQS software program.

Highest correlations between pairs of constructs.

CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted.

Frequency of past behavior was not included in the measurement model because it was a single indicator.

4.2. TRA, TPB, and EMGB tests

In Table 2 , the TRA model had a good fit to the data (χ2 = 84.549, df = 74, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 1.143, RMSEA = 0.019; CFI = 0.996; NFI = 0.972). Attitude toward a behavior and subjective norm explained 53.4% of the total variance of intention. The TPB model had a sufficient fit to the data (χ2 = 160.127, df = 128, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 1.251, RMSEA = 0.025; CFI = 0.992; NFI = 0.960). Three antecedent variables (i.e., attitude, subjective norm, and PBC) accounted for approximately 57.3% of the variance of intention to travel internationally. The value of R2 for intention improved slightly from 0.534 to 0.573. Finally, the EMGB showed an excellent fit to the data (χ2 = 1087.184, df = 785, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 1.385, RMSEA = 0.031; CFI = 0.967; NFI = 0.891). The value of R2 for intention was 0.793.

Table 2.

Modeling comparisons.

| S–B χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | NFI | R2 for BI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRA | 84.549 | 74 | 1.143 | 0.019 | 0.996 | 0.972 | 0.534 |

| TPB | 160.127 | 128 | 1.251 | 0.025 | 0.992 | 0.960 | 0.573 |

| EMGB | 1087.184 | 785 | 1.385 | 0.031 | 0.967 | 0.891 | 0.793 |

| Suggested value∗ | ≤3 | ≤ 0.08 | ≥ 0.90 | ≥ 0.90 |

Note: Suggested values were based on Hair et al. (2006), and Bearden and Etzel (1982). RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; NFI = nonnormed fit index.

4.3. Comparing the three models

The three competing models, the TRA, the TPB, and the EMGB, were compared for their relative explanatory power. First, the TPB model had a better explanatory power than the TRA model. Specifically, three predictor variables (attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control) in the TPB model explained approximately 57.3% of the total variance in the behavioral intention to travel internationally while both attitude and subjective norm jointly explained about 53.4% of the total variance in the TRA model (Table 2). These findings were consistent with previous research in other settings (Ajzen and Madden, 1986, Chang, 1998) and imply that including perceived behavioral control did play a significant role in predicting behavioral intention. Second, the TPB model was slightly better in fit statistics, but the model still lacks the explanatory power of behavioral intention as compared to the EMGB. That is, the EMGB improved R2 largely from 0.573 to 0.793.

Chi-square tests indicate there was significant difference between these two models (Δχ2 (657) = 931.10, p < 0.001). The MGB better accounted for the variance in explaining behavioral intention. This model was superior to the TRA model for explanatory power (EMGB = 0.793 vs. TRA = 0.534, Δχ2 (711) = 1008.41, p < 0.001). Consistent with other research (Bagozzi and Dholakia, 2006, Carrus et al., 2008, Prestwich et al., 2008, Prestwich et al., 2008, Taylor et al., 2005) the results showed the EMGB with desire, positive anticipated emotion, negative anticipated emotion, and frequency of past behavior performs better than the TRA and TPB models. Enhancing our understanding of the decision process of behavioral intention these results prompt several suggestions. The TPB is inadequate for explaining behavioral intention to travel internationally, and the processes behind the effect of the predictors are more intricate than assumed in the TPB (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2001).

4.4. Test of hypotheses

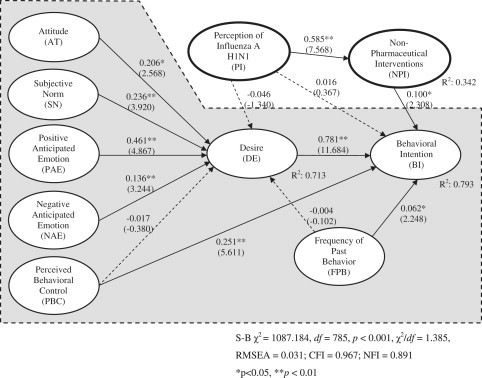

As shown in Fig. 1 , four predictor variables (attitude, subjective norm, positive anticipated emotion, and negative anticipated emotion) in the EMGB were positively associated with desire to travel internationally (βAT→DE = 0.206, t = 2.568, p < 0.01; βSN→DE = 0.236, t = 3.920, p < 0.01; βPAE→DE = 0.461, t = 4.867, p < 0.01; βNAE→DE = 0.136, t = 3.244, p < 0.01). This implies an individual’s desire is a significant function of attitude, subjective norm, positive anticipated emotion, and negative anticipated emotion. However, the findings indicate that PBC, frequency of past behavior, and perception of 2009 H1N1 did not have a significant influence on desire (βPBC→DE = −0.017, t = −0.380, not significant; βFPB→DE = −0.004, t = −0.102, not significant; βPI→DE = −0.046, t = −1.340, not significant). Thus, hypotheses H1, H2, H5, and H6 were accepted, but H3, H7, and H10 were rejected.

Fig. 1.

Results of the extended model of goal-directed behavior. Note: Shaded area shows the basic components of the MGB and the two bold ovals with italics are the additional constructs of PI and NPI that contribute to developing the EMGB.

The relationships between the perception of 2009 H1N1 and NPI were found positive and significant (βPI→NPI = 0.585, t = 7.568, p < 0.01). Therefore H11 was supported. Four predictor variables (desire, PBC, frequency of past behavior, and NPI) were positively associated with intention to travel internationally (βDE→BI = 0.781, t = 11.684, p < 0.01; βPBC→BI = 0.251, t = 5.611, p < 0.01; βFPB→BI = 0.062, t = 2.248, p < 0.01; βNPI→BI = 0.100, t = 2.308, p < 0.01). Thus, hypotheses H9, H4, H8, and H13 were accepted. This implies that desire, PBC, frequency of past behavior, and NPI are important in an individual’s intention to travel internationally. However, the path from 2009 H1N1 to intention was not significant (βPI→BI = 0.016, t = 0.367, p > 0.05), not supporting the proposition that 2009 H1N1 has a negative effect on intention. So, H12 was rejected.

4.5. Indirect and total effects

As Table 3 shows, when predicting behavioral intention desire was the important factor with an impact of 0.781, followed by positive anticipated emotion (0.360), perceived behavioral control (0.238), subjective norm (0.184), attitude (0.161), negative anticipated emotion (0.106), and NPI (0.100). When predicing desire the powerful factor was positive anticipated emotion with a total impact of 0.461, followed by subjective norm (0.236), attitude (0.206), and negative anticipated emotion (0.136). The perception of 2009 H1N1 indirectly effected travel intention when it is mediated by personal NPI (see Fig. 1). Although the perception of 2009 H1N1 had no effect on desire and behavioral intention, the NPI for 2009 H1N1 was a significant predictor of behavioral intention to travel internationally. The four constructs of desire, perceived behavioral control, frequency of past behavior, and NPI, all performed an important role in predicting potential tourists’ behavioral intention to travel internationally.

Table 3.

Decomposition of effects with standardized values.

| Direct effect | Indirect effect | Total effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | NPI | BI | DE | NPI | BI | DE | NPI | BI | |

| AT | 0.206∗∗ | – | – | – | – | 0.161∗∗ | 0.206∗∗ | – | 0.161∗∗ |

| SN | 0.236∗∗ | – | – | – | – | 0.184∗∗ | 0.236∗∗ | – | 0.184∗∗ |

| PBC | −0.017 | – | 0.251∗∗ | – | – | −0.013 | −0.017 | – | 0.238∗∗ |

| PAE | 0.461∗∗ | – | – | – | – | 0.360∗∗ | 0.461∗∗ | – | 0.360∗∗ |

| NAE | 0.136∗∗ | – | – | – | – | 0.106∗∗ | 0.136∗∗ | – | 0.106∗∗ |

| PI | −0.046 | 0.585∗∗ | 0.016 | – | – | 0.022 | −0.046 | 0.585∗∗ | 0.039 |

| NPI | – | – | 0.100∗∗ | – | – | – | – | – | 0.100∗∗ |

| FPB | −0.004 | – | 0.062∗∗ | – | – | −0.003 | −0.004 | – | 0.059 |

| DE | – | – | 0.781∗∗ | – | – | – | – | – | 0.781∗∗ |

∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, n/s: not significant Note: AT = attitude; SN = subjective norm; PBC = perceived behavioral control; PAE = positive anticipated emotion; NAE = negative anticipated emotion; FPB = frequency of past behavior; PI = perception of Influenza A (H1N1); NPI = non-pharmaceutical interventions; DE = desire; BI = behavioral intention.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Travel desire and adaptive behavior

Knowledge is limited about how the 2009 H1N1 pandemic impacted potential international tourists’ decision-making although it is assumed that tourists’ apprehension of contracting 2009 H1N1 while traveling affected the tourism industry negatively. To the authors’ awareness, this is the first trial which focused on improving predictions of international tourists’ travel intention and decision-making using an extended model of the MGB. In specific, this approach included the perception of 2009 H1N1 and the personal NPI for 2009 H1N1. The EMGB incorporated the construct of desire as a mediator which considered volitional factors (attitude and subjective norm), non-volitional factors (perceived behavioral control, the perception of 2009 H1N1, and the NPI for 2009 H1N1), emotional factors (positive anticipated emotion and negative anticipated emotion), and the frequency of past behavior. Also, including both the perception of 2009 H1N1 and personal NPI in the EMGB were supported by the model’s increased power in predicting potential tourists’ intention to travel internationally.

Showing its superior predictive validity the EMGB accounted for significantly more variance in travel intention than either the TRA or the TPB, which is an improvement in explaining potential international tourists’ intentions. Demonstrating, in this context, that theory broadening and deepening as described by Perugini and Bagozzi (2001) is reasonable by integrating new constructs or by altering the paths to be more appropriate in the model. So, the revised model explains a substantial proportion of the total variance of the dependent variable of intention in this study. Also, consistent with previous studies of MGB (e.g., Bagozzi and Dholakia, 2006, Carrus et al., 2008, Taylor, 2007) desire as a sufficient impetus for intention formation was the most important latent variable. In the model, the more important determinants to desire were the emotional factors, specifically positive anticipated emotion while the other determinants such as the subjective norm, attitude, and negative anticipated emotions are less important to the prediction of desire. It is not problematic that all antecedent variables in the EMGB do not make a considerable contribution to behavioral intention because the relative importance of individual antecedent variables in a model may differ based on given contexts (Sparks & Pan, 2009).

It is noteworthy the perception of 2009 H1N1 was not a significant (direct) predictor of either desire or behavioral intention although some previous research proposed possible relationships among the perceptions of a disease, the response to that disease, attitude, and intention (Reisinger and Mavondo, 2005, Sonmez and Graefe, 1998). However, it did influence international travel intentions indirectly through personal NPI. This Korean data suggests that the perception of 2009 H1N1 did not constrain the desire for international travel among potential tourists as they had some adaptive behavior in mind which lowered the infection threat to a level acceptable to them. In effect, personal NPI are an adaptive behavior which reinforce the desire that supports their behavioral intention. This coincides with the findings of Raude and Setbon (2009, p. 342) that the French public has moderately adaptive beliefs and attitudes about new infectious respiratory illnesses which lead them to personal NPI as a means for lowering contagion risks.

5.2. Implications for global tourism and future research

Recognizing personal NPI for 2009 H1N1 as an adaptive behavior among tourists infers four significant implications for government agencies, tourism marketers, transport systems, and hospitality services which raise opportunities for practical suggestions. First, the intention to travel internationally is resilient during a global pandemic because potential international tourists perceive personal NPI like hand washing, mask wearing, and information gathering as plausible protective behaviors while taking a trip. This approach may not be shared by all tourists because socioeconomic characteristics are linked to variations in health outcomes (Raude & Setbon, 2009), so educational initiatives are needed. For example, guidelines for NPI hygiene should be continually available alongside other safety information in airline onboard publications. Also, tourism operators can improve their online communications concerning pandemic diseases to reassure tourists of their relative safety and reduce their apprehension about traveling. Second, in addition to public restrooms, transport and hospitality services should provide convenient NPI hygiene and information kiosks within their facilities which support self-protective health behavior by staff, passengers, or guests. Because personal NPI are the adaptive behavior of many potential tourists who wish to proceed with their journey during a pandemic when uncertainty surrounds administrative disease control measures and the efficacy and availability of pharmaceutical interventions. For example, if designed for high usage these kiosks can provide multiple hand cleaning devices and multi-lingual displays of current health risks at regular locations in airport boarding lounges.

Third, similar to green tourism certification, tourism operators and governments should establish a validation system for NPI friendly businesses which continuously support the personal NPI actions of their staff, passengers or guests. Because the global reach of novel influenza-like viruses and the limits of mandatory administrative NPI, such as border control and passenger screening techniques, provide tourism businesses with opportunities for good corporate citizenship and for health related competitive advantages. For example, transport systems and hospitality services should implement staff training in personal NPI for their own benefit and for them to better assist their passengers and their guests. This could be promoted as a “Green & Clean” certification process developed by cooperation between tourism businesses and health agencies. Businesses that are accredited with better hygiene support for their passengers or guests should have a positive brand identity in the minds of potential tourists who are planning their next trip.

Four, government agencies, tourism marketers, transport systems, and hospitality services should adopt the system-wide tourism industry approach of a permanent, as opposed to an episodic, disease mitigation strategy which supports personal responsibility for staff, passenger or guest health. At a planetary scale influenza pandemics are a continuous risk due to a combination of issues. These are the complexity and rapidity of the global air transport; the practical and technological constraints on border controls and passenger screening; the influenza virus’s antigenic changeability; and the limited efficacy of antiviral drugs and vaccines. For example, to combat the complexity of these issues international and national governmental tourism organizations should give health, hygiene, and disease prevention equal status with sustainability or security as a policy priority.

Future research suggestions that reinforce these approaches include longitudinal studies of the effect of global pandemics on tourists’ intentions and their approach to personal NPI as pandemic alert levels vary over time. Also, as we focused on Korean tourists, new research should address variations of nationality and socioeconomic status among tourists to discover the communication and education issues surrounding pandemic disease awareness, and the use of personal NPI and travel behavior. Finally, identifying the NPI hygiene techniques which are practical in diverse tourism setting and the actions required to modify tourist behavior accordingly, require research attention.

Contributor Information

Choong-Ki Lee, Email: cklee@khu.ac.kr.

Hak-Jun Song, Email: bloodia00@hotmail.com.

Lawrence J. Bendle, Email: bendle@khu.ac.kr.

Myung-Ja Kim, Email: silver@khu.ac.kr.

Heesup Han, Email: heesup@donga.ac.kr.

Appendix. Operational definitions of the measures

| Construct | Operational definition |

|---|---|

| Attitude (AT) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) |

| I think that traveling internationally is positive. | |

| I think that traveling internationally is useful. | |

| I think that traveling internationally is valuable. | |

| I think that traveling internationally is dynamic. | |

| I think that traveling internationally is attractive. | |

| I think that traveling internationally is enjoyable.∗ | |

| I think that traveling internationally is delightful. | |

| Subjective norm (SN) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) |

| Most people who are important to me think it is okay for me to travel internationally. | |

| Most people who are important to me support that I travel internationally. | |

| Most people who are important to me understand that I travel internationally. | |

| Most people who are important to me agree with me about traveling internationally | |

| Most people who are important to me recommend traveling internationally.∗ | |

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) |

| Whether or not I travel internationally is completely up to me.∗ | |

| I am capable of traveling internationally. | |

| I am confident that if I want, I can travel internationally. | |

| I have enough resources (money) to travel internationally. | |

| I have enough time to travel internationally. | |

| I have enough opportunities to travel internationally.∗ | |

| Perception of Influenza A (H1N1) (PI) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) |

| It is dangerous to travel internationally because of Influenza A (H1N1). | |

| Influenza A (H1N1) is a very frightening disease. | |

| Compared to SARS and avian flu, Influenza A (H1N1) is more dangerous. | |

| I have much information about Influenza A (H1N1).∗ | |

| I am afraid of Influenza A (H1N1). | |

| People around me seem to refrain from traveling internationally due to Influenza A (H1N1).∗ | |

| Desire (DE) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) |

| I want to travel internationally in the near future. | |

| I wish to travel internationally in the near future. | |

| I am eager to travel internationally in the near future. | |

| My wish to travel internationally in the near future can be described desirably. | |

| Frequency of past behavior (FOP) | How many times have you traveled internationally in the past 12 months? |

| Non-pharmaceutical interventions for Influenza A(H1N1) (NPI) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) |

| I will check the information of on Influenza A (H1N1) by visiting the website of the Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs or WTO before traveling internationally. | |

| I will read and check precautions about Influenza A (H1N1) through doctors or health centers before traveling internationally. | |

| I will prepare a first aid kit for Influenza A (H1N1) before traveling internationally.∗ | |

| I will get the information about local medical facilities and Korean Embassy for preparing for an emergency because of Influenza A (H1N1) before traveling internationally. | |

| I will frequently wash my hands while traveling internationally. | |

| I will restrain from touching my eyes, nose, and mouth while traveling. | |

| I will cover my mouth and nose with a tissue when sneezing while traveling internationally.∗ | |

| I will keep away from those who have the symptoms of Influenza A (H1N1) while traveling internationally. | |

| I will restrain from meeting people for a while after traveling internationally.∗ | |

| I will carefully keep an eye on my health condition after traveling internationally. | |

| Anticipated emotion (AE) | Not At All (1) to Very Much (7) |

| If I succeed in achieving my goal of traveling internationally, I will be excited. | |

| If I succeed in achieving my goal of traveling internationally, I will be glad. | |

| If I succeed in achieving my goal of traveling internationally, I will be satisfied. | |

| If I succeed in achieving my goal of traveling internationally, I will be happy. | |

| If I succeed in achieving my goal of traveling internationally, I will be proud.∗ | |

| If I fail in achieving my goal of traveling internationally, I will be unsatisfied.∗ | |

| If I fail in achieving my goal of traveling internationally, I will be angry. | |

| If I fail in achieving my goal of traveling internationally, I will be disappointed. | |

| If I fail in achieving my goal of traveling internationally, I will be worried. | |

| If I fail in achieving my goal of traveling internationally, I will be sad. | |

| Behavioral intention (BI) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) |

| I intend to travel internationally in the near future. | |

| I am planning to travel internationally in the near future. | |

| I will make an effort to travel internationally in the near future. | |

| I will certainly invest time and money to travel internationally in the near future. | |

| I am willing to travel internationally in the near future.∗ | |

Note: Based on the results of EFA and CFA. ∗ items were excluded from further analyses.

References

- Aarts H., Verplanken B., van Knippenberg A. Predicting behavior from actions in the past: repeated decision making or a matter of habit? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1998;28(15):1355–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J., Beckman J., editors. Action-control: From cognition to behavior. Springer; Heidelberg: 1985. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I., Madden T. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitude, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1986;22(5):453–474. [Google Scholar]

- Aledort J., Lurie N., Wasserman J., Bozzette S. Non-pharmaceutical public health interventions for pandemic influenza: an evaluation of the evidence base. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:208–216. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.R. Worth Pub; NY: 2004. Cognitive psychology and its implications. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J., Gerbing D. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(3):411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Aro A.R., Vartti A.M., Schreck M., Turtiainen P., Uutela A. Willingness to take travel-related health risks: a study among the Finnish tourists in Asia during the Avian influenza outbreak. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;16(1):68–73. doi: 10.1007/s12529-008-9003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R.P. The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1992;55(2):178–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R., Baumgartner H., Pieters R. Goal-directed emotions. Cognition and Emotion. 1998;12(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R., Dholakia U. Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 2006;23(1):45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R., Warshaw P. An examination of the etiology of the attitude-behavior relation for goal-directed behaviors. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1992;27(4):601–634. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2704_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker E.W., Al-Gahtani S.S., Hubona G.S. The effects of gender and age on new technology implementation in a developing country: testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB) Information Technology & People. 2007;20(4):352–375. [Google Scholar]

- Bearden W.O., Etzel M.J. Reference group influence on products and brand purchase decisions. Journal of Consumer Research. 1982;9(2):183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P., Speckart G. Attitudes “cause” behaviors: a structural equation analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1981;40(2):226–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P., Wu E. Multivariate Software, Inc; Encino, CA: 1995. EQS for windows: User’s guide. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K. Wiley; NY: 1989. Structural equations with latent variables. [Google Scholar]

- Brug J., Aro A.R., Oenema A., De Zwart O., Richardus J.H., Bishop G.D. SARS risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, The Netherlands. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(8):1486–1489. doi: 10.3201/eid1008.040283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B. Testing for the factorial validity, replication, and invariance of a measuring instrument: a paradigmatic application based on the Maslach burnout inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1994;29(3):289–311. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2903_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. Structural equation modeling with EQS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. [Google Scholar]

- Carrus G., Passafaro P., Bonnes M. Emotions, habits and rational choices in ecological behaviours: the case of recycling and use of public transportation. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2008;28(1):51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chang M.K. Predicting unethical behavior: a comparison of the theory of reasoned action and theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics. 1998;17(16):1825–1834. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi S. Pandemic influenza: imminent threat, preparedness and the divided globe. Indian Pediatric. 2009;46(2):115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Lam T., Hsu C. Negative word-of-mouth communication intention: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. 2006;30(1):95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Conner M., Abraham C. Conscientiousness and the theory of planned behavior: towards a more complete model of the antecedents of intentions and behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(11):1547–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Conner M., Armitage C. Extending the theory of planned behavior: a review of the literature and avenues for future research. Journal of Applied and Social Psychology. 1998;28(15):1429–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services . 2009. Assessment of the 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic on selected countries in the Southern Hemisphere: Argentina, Australia, Chile, New Zealand and Uruguay.http://www.flu.gov/professional/global/southhemisphere.html Retrieved December 15, 2009 from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embrain . 2009. Online survey.http://www.embrain.com Retrieved October 21, 2009 from the official website of Embrain. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson N., Cummings D., Fraser C., Cajka J., Cooley P., Burke D. Strategies for mitigating an influenza pandemic. Nature. 2006;442(7101):448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature04795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein S., Prakash S., Nigmatulina K., Klaiman T., Larson R. Pandemic influenza: non-pharmaceutical interventions and behavioral changes that may save lives. 2009. http://blossoms.mit.edu/video/larson2/larson2-state-plans.pdf Retrieved December 15, 2009 from.

- Fornell C., Larcker D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(1):39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks A., Dossett D. Attitude behavior relations: a comparison of the Fishbein–Ajzen and Bentler–Speckart models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45(3):501–512. [Google Scholar]

- Gleicher F., Boninger D.S., Strathman A., Armor D., Hetts J., Ahn M. With an eye toward the future: the impact of counterfactual thinking on affect, attitudes, and behavior. In: Roese N.J., OlsonMahwah J.M., editors. What might have been: The social psychology of counterfactual thinking. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. pp. 283–304. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Jr., Black W.C., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E., Tatham R.L. Pearson Education; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2006. Multivariate data analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Han H., Hsu L., Lee J. Empirical investigation of the roles of attitudes toward green behaviors, overall image, gender, and age in hotel customers’ eco-friendly decision-making process. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2009;28(4):519–528. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher L. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1994. A step-by-step approach to using the SAS Systems for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Jeeninga R.E., de Jong M.D., Berkhout B. The New influenza A (H1N1) pandemic. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2009;108(7):523–525. doi: 10.1016/s0929-6646(09)60368-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan K., Arino J., Hu W., Raposo P., Sears J., Calderon F. Spread of a novel Influenza A (H1N1) Virus via global airline transportation. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(2):212–214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0904559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W., Ok C. The effects of relational benefits of favorable inequity, affective commitment, and repurchase intention in full-service restaurants. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research. 2009;33(2):227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. Guilford Press; NY: 2005. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Kolata G. Touchstone; NY: 2001. Flu: The story of the great influenza pandemic of 1918 and the search for the virus that caused it. [Google Scholar]

- Lam T., Hsu C. Theory of planned behavior: potential travelers from China. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research. 2004;28(4):463–482. [Google Scholar]

- Lam T., Hsu C. Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tourism Management. 2006;27(4):589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Leone L., Perugini M., Ercolani A. A comparison of three models of attitude–behavior relationships in the studying behavior domain. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1999;29(2–3):161–189. [Google Scholar]

- Leone L., Perugini M., Ercolani A. Studying, practicing, and mastering: a test of the model of goal-directed behavior (MGB) in the software learning domain. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004;34(9):1945–1973. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher B., Chon K. The over-reaction to SARS and the collapse of Asian tourism. Annals of Tourism Research. 2004;31(3):716–719. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason P., Grabowski P., Du W. Severe acute respiratory syndrome, tourism and the media. The International Journal of Tourism Research. 2005;7(1):11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs . 2009. The growth trend of Influenza A (H1N1)http://www.mw.go.kr/front/al/sal0301vw.jsp? Retrieved October 21, 2009 from. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs . 2009. The code of preventing Swine Flu.http://online.mw.go.kr/influenza/01_01.jsp Retrieved October 21, 2009 from. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann G., Noda T., Kawaoka Y. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature. 2009;459(7249):931–939. doi: 10.1038/nature08157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholl A. 2006. Personal (non-pharmaceutical) protective measures for reducing transmission of influenza: ECDC interim recommendations.http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx? ArticleId=3061 Retrieved October 29, 2009 from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J. McGraw-Hill; NY: 1978. Psychometric theory. [Google Scholar]

- Oh H., Hsu C. Volitional degrees of gambling behaviors. Annals of Tourism Research. 2001;28(3):618–637. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver R.L. McGraw-Hill; NY: 1997. Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. [Google Scholar]

- Omi S. WHO Press; Geneva, Switzerland: 2006. SARS: How a global epidemic was stopped. [Google Scholar]

- Oshitani H. Potential benefits and limitations of various strategies to mitigate the impact of an influenza pandemic. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy. 2006;12(4):167–171. doi: 10.1007/s10156-006-0453-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette J.A., Wood W. Habit and intention in everyday life: the multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124(1):54–74. [Google Scholar]

- Perugini M., Bagozzi R. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviors: broadening and deepening the theory of planned behavior. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40(1):79–98. doi: 10.1348/014466601164704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pligt J., De Vries N.K. Expectancy-value models of health behaviour: the role of salience and anticipated affect. Psychology & Health. 1998;13(2):289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Prestwich A., Perugini M., Hurling R. Goal desires moderate intention–behaviour relations. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;47(1):49–71. doi: 10.1348/014466607X218221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raude J., Setbon M. Lay perceptions of the pandemic influenza threat. European Journal Epidemiology. 2009;24(7):339–342. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9351-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger Y., Mavondo F. Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: implications of travel risk perception. Journal of Travel Research. 2005;43(3):212–225. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo C., degli Atti M.L.C. Modeling influenza pandemic and interventions. In: Rappouli R., Del Guidice G., editors. Influenza vaccines for the future. Birkhauser Verlag; Basel, Switzerland: 2008. pp. 281–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sonmez S.F., Graefe A.R. Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. Journal of Travel Research. 1998;37(2):171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks B., Pan G.W. Chinese outbound tourists: understanding their attitudes, constraints and use of information sources. Tourism Management. 2009;30(4):483–494. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Package for the Social Sciences . SPSS Inc; Chicago, IL: 2001. SPSS base 11.0 user’s guide. [Google Scholar]

- St. Michael’s Hospital . 2009. The Bio. Diaspora project report 2009: An analysis of Canada’s vulnerability to emerging infectious disease threats via the global airline transportation network.http://www.biodiaspora.com/ Retrieved October 21, 2009 from. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S.A. The addition of anticipated regret to attitudinally based, goal-directed models of information search behaviours under conditions of uncertainty and risk. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2007;46(4):739–768. doi: 10.1348/014466607X174194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S., Bagozzi R., Gaither C. Decision making and effort in the self-regulation of hypertension: testing two competing theories. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10(4):505–530. doi: 10.1348/135910704X22376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S., Todd P. Assessing IT usage: the role of prior experience. MIS Quarterly. 1995;19(4):561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis H.C. Brooks/Cole; Monterey, CA: 1977. Interpersonal behavior. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . Vol. 7. 2009. http://www.unwto.org/facts/eng/pdf/barometer/UNWTO_Barom09_2_en.pdf (UNWTO World Tourism Barometer). (2). Retrieved March 18, 2010 from. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . Vol. 7. 2009. http://www.unwto.org/facts/eng/pdf/barometer/UNWTO_Barom09_3_en.pdf (UNWTO World Tourism Barometer). (3). Retrieved March 18, 2010 from. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . 2009. Influenza A (H1N1): No restrictions on travel recommended.http://www.unwto.org/media/news/en/press _det.php?id=4071 Retrieved October 21, 2009 from. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO . Vol. 8. 2010. http://unwto.org/facts/eng/pdf/barometer/UNWTO_Barom10_1_en_excerpt.pdf (UNWTO World Tourism Barometer). (1). Retrieved March 18, 2010 from. [Google Scholar]

- Varia M., Wilson S., Sarwal S., McGeer A., Gournis E., Galanis E. Investigation of a nosocomial outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Toronto, Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2003;169(4):285–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2009. Clinical features of severe cases of pandemic influenza.http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/h1n1_clinical_features_20091016/en/index.htm Retrieved October 21, 2009 from. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2009. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009-Update 70.http://www.who.int/csr/don/2009_10_16/en/index.html Retrieved October 25, 2009 from. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2009. Global alert and response (GAR): Travel.http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/frequently_asked_questions/travel/en/index.html Retrieved October 23, 2009 from the official website of WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Wu E., Law R., Jiang B. The impact of infectious diseases on hotel occupancy rate based on independent component analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2010;29(4):751–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y., Uysal M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model. Tourism Management. 2005;26(1):45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zint M. Comparing three attitude-behavior theories for predicting science teachers’ intentions. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 2002;39(9):819–844. [Google Scholar]