Abstract

Background

Prior text analysis of R01 critiques suggested that female applicants may be disadvantaged in NIH peer review, particularly for R01 renewals. NIH altered its review format in 2009. The authors examined R01 critiques and scoring in the new format for differences due to principal investigator (PI) sex.

Method

The authors analyzed 739 critiques—268 from 88 unfunded and 471 from 153 funded applications for grants awarded to 125 PIs (M = 76, 61% F = 49, 39%) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison between 2010 and 2014. The authors used 7 word categories for text analysis: ability, achievement, agentic, negative evaluation, positive evaluation, research, and standout adjectives. The authors used regression models to compare priority and criteria scores, and results from text analysis for differences due to PI sex and whether the application was for a new (Type 1) or renewal (Type 2) R01.

Results

Approach scores predicted priority scores for all PIs’ applications (P<.001); but scores and critiques differed significantly for male and female PIs’ Type 2 applications. Reviewers assigned significantly worse priority, approach, and significance scores to female than male PIs’ Type 2 applications, despite using standout adjectives (e.g., “outstanding,” “excellent”) and making references to ability in more of their critiques (P<.05 for all comparisons).

Conclusions

The authors’ analyses suggest that subtle gender bias may continue to operate in the post-2009 NIH review format in ways that could lead reviewers to implicitly hold male and female applicants to different standards of evaluation, particularly for R01 renewals.

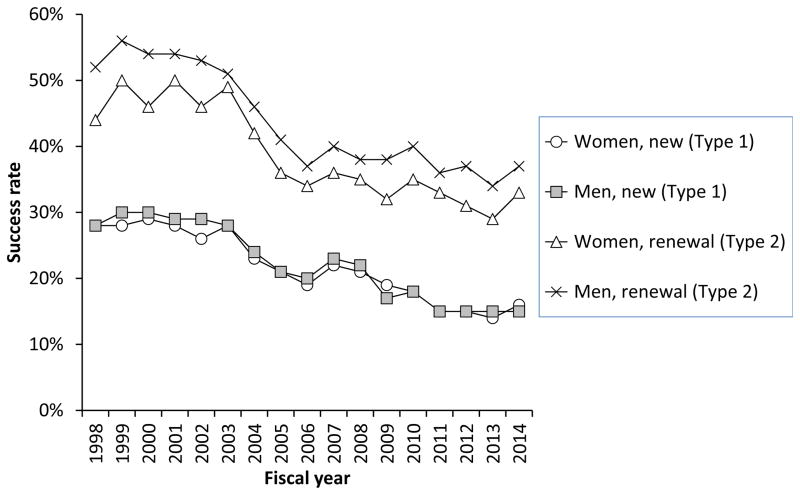

Despite the near gender parity seen in early career stages in academic medicine since the 1990s, women remain underrepresented in advanced ranks and leadership.1 Obtaining and renewing R01 grant funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is important for leadership attainment.2 Although male and female applicants have similar success rates for new (Type 1) R01s,3–6 female investigators have lower success rates than their male counterparts for R01 renewals (Type 2), with no appreciable change for the past 15 years in the average yearly difference of 5 percentage points (Figure 1).3,4,6,7 Disparities in R01 renewal success rates likely contribute to the premature departure of many female physicians and scientists from research careers, precluding their ascent to top leadership in academic medicine. These data raise the possibility that gender bias may operate in NIH peer review.

Figure 1.

Success rates for male and female investigators of NIH Type 1 or Type 2 R01 or equivalent awards, 1998–2014, from a study of 739 R01 grant critiques and Scores, University of Wisconsin-Madison, fiscal years 2010–2014. Data source: Office of Extramural Research, National Institutes of Health. NIH Research Project Grant Program (R01). http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/r01.htm.

Abbreviation: NIH indicates National Institutes of Health.

The NIH uses a two-phased system of peer review to evaluate the merit of research proposals.8 In the first phase, reviewers assign scores and write critiques to evaluate each application.8 Applications with priority scores in the top half are later discussed and rescored at review meetings before being sent on to the second stage of review, where NIH staff and Advisory Councils for each Institute and Center (IC) make recommendations to IC directors for funding decisions.8

Extensive research documents women’s disadvantage in review processes for hiring, promotion, performance, and receipt of awards in fields that have historically been dominated by men, such as science.9–28 Such evaluation bias arises from gender stereotypes that characterize women without the “agentic” traits (e.g., independence, logic) associated with ability in male-typed fields, and can lead to the implicit assumption that women are less competent than men in these fields.10,14,29,30 Experiments show that this assumption can cause reviewers to hold women to higher performance standards than men by requiring more proof of their ability to confirm their comeptence.10,14,29,30 Such bias in judgment is often unconscious, unintentional,31,32 and demonstrated by both male and female evaluators equally.31,33

Our previous work suggests that text analysis of grant critiques may be useful for identifying potential gender bias in peer review.16 In a sample of R01 application critiques and scores from 2008, we found that greater praise and fewer negative evaluation words did not translate into better priority scores or funding outcomes for female principal investigators (PIs).16 The greatest differences occurred for female and male PIs of Type 2 R01s, where critiques for female PIs’ applications also showed significantly more words about ability and competence. These findings are consistent with research on gender bias in evaluative judgment and suggest that NIH peer reviewers could implicitly hold male and female PIs to lower and higher standards respectively, particularly for R01 renewals.

In 2009, the NIH altered its review process by changing the scoring scale from 5 points to 9 points (where 1 is the best and 9 is the worst score); introducing the use of separate “criterion scores” to assess the approach, significance, innovation, investigator(s), and environment in addition to the priority score; and replacing the narrative critique with a bullet-point format that outlines strengths and weaknesses to justify scores for each criterion section.8,34,35 In the current study we analyzed priority and criteria scores and reviewers’ critiques derived from a sample of applications spanning fiscal years 2010 to 2014 for differences due to the sex of the applicant (M vs. F), and the type of application (new project/Type 1 vs. renewal/Type 2).3,6 We hypothesized that application priority and criteria scores, and categories of words in critiques, would differ in ways that suggest the use of different evaluative standards for male and female PIs, particularly when they apply for R01 renewals.

Method

Data collection

We queried the NIH’s public access database, Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORTER), to identify all principal investigators (PIs) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) who received Type 1 or Type 2 R01 grants funded on the first submission or after revision during fiscal years 2010 through 2014. We sent PIs 3 email invitations to participate indicating that consent consisted of sending electronic copies of Summary Statements (i.e., the document containing application scores and critiques) from the funded (and, when applicable, unfunded) submission(s) of their eligible awards. Consent text explained that participation was voluntary and that PIs could withdraw from the study at any time.

Participation

Between 2010 and 2014, 352 R01 grants (Type 1 = 217, 62%; Type 2 = 135, 38%) were awarded to 278 UW-Madison PIs (M = 188, 68%; F = 90, 32%). Notice of grant award dates spanned November 13, 2009, through September 26, 2014. Approximately half (47%, 132/278) of all PIs participated by sending us Summary Statements from 161 grants. Participants (P) matched nonparticipants (NP; 146/278) on PI race/ethnicity [P: 85% White (112/132) vs. NP: 82% White (119/146)]; school within UW-Madison—with over half as faculty in the School of Medicine and Public Health (SMPH) [P: 53% SMPH (70/132) vs. NP: 52% SMPH (76/146)]; and NIH funding ICs (P: 21 ICs vs. NP: 20 ICs). A higher percentage of female (52/90, 58%) than male (80/188, 42%) PIs participated.

Characteristics of analytic sample

We excluded data from grants funded after revision when the first set of reviews was in the NIH’s old format (8/161, 5%). For participating PIs with grants funded after revision we did not receive 2 unfunded and 9 funded application Summary Statements. Our final analytic sample consisted of 739 critiques, 268 from 88 unfunded and 471 from 153 funded applications for grants awarded to 125 PIs (M = 76, 61%; F = 49, 39%). Each Summary Statement contained between 2 and 5 critiques. Approximately half the applications were funded after revision (84/153, 55%). Approximately a third (56/153, 37%) were for clinical research. Applications were reviewed by 103 NIH study sections and funded by 21 NIH institutes.

PIs in our final sample represented 30 different UW-Madison departments. Most were male (M = 76/125, 61%; F = 49/125, 39%), White (112/125, 90%), and held PhDs (PhD = 95/125, 76%; MDs = 18/125, 14%; MD/PhDs = 12/125, 10%). Approximately one third (41/125, 33%) were new investigators.5 Most (103/125, 82%) contributed Summary Statements from one award, but 19 (15%) contributed Summary Statements from two awards, and 3 (2%) contributed Summary Statements from three awards.

Database development

Summary Statements contain applicant and study section (i.e., review group) information; a priority score (if the proposal was discussed); and usually three sets of individual reviewers’ critiques and criteria scores. Each criterion within a critique is further split into strengths and weaknesses subsections.8 We assigned each PI, Summary Statement, and critique within each Summary Statement unique identifiers (IDs). Using R (version 3.1.1;Vienna, Austria; 2015) and the auxiliary packages “Hmisc,” (version 3.14; M. Harrell, 2014), “RWeka,” (Hornik, Buchta & Zeileis, 2009; Witten & Frank, 2005) and “tm,” (version .6; Feinerer & Hornik, 2014), we wrote a program to parse Summary Statements and extract applicant [academic/professional degree(s), experience level (new/first time independent award applicant vs. experienced/previous independent awardee)36]; application [R01 Type, clinical research as indicated with a human subjects identifier]; and scoring information (priority and criteria scores). This program also parsed bulleted text associated with each criterion’s strengths and weaknesses subsection. We manually retrieved information on applicant sex, applicant race/ethnicity, and funding outcome which are not contained in Summary Statements and merged it with the program output. We used the methods of Jagsi et al.37 and Kaatz et al.16 to identify applicant sex and race/ethnicity, which involved searching the internet for pictures, text with descriptions of PIs and their research, and CVs (this provided us pictures and text with pronouns to resolve cases of gender ambiguity; and information to identify country of origin, awards, or memberships to assign race/ethnicity).16,37 Two independent coders (A.F., R.L.) assigned PI sex and race/ethnicity—disagreements were resolved by the first and last author (A.K., M.C.).

Analytic strategy

Priority and criteria scores

To test our hypothesis that scores would differ significantly by PI sex with the greatest differences for male and female PIs’ renewal applications, we transformed all scores to a logarithmic scale, because they were skewed, and submitted them as dependent variables for ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression with PI sex (M vs. F), application type (Type 1/new vs. Type 2/renewal), and the interaction term between PI sex and application type as predictor variables. Models used standard errors clustered at the applicant level; and adjusted for experience level (new vs. experienced investigator) and funding outcome (unfunded vs. funded). Due to a smaller sample size of priority scores (218, 1/Summary Statement) than criteria scores (680, 2–4 sets/Summary Statement), we included interaction terms between both PI sex and experience level and PI sex and funding outcome only in models predicting criteria scores.

Quantitative text analysis of critiques and subsections

We wrote an R program that matched the Linguistic Inquiry Word Count (LIWC, 2007) program used in our previous study16,38 and used it to detect 7 categories of words relevant to scientific grant evaluation in each critique and criteria subsection (see Kaatz et al16 for full lists of words in each category):16,18,22,24,38,39 ability (e.g., able, skill),16,22,24,39 achievement (e.g., awards, honors),16,38 agentic (e.g., competent, leader),16,18,39 negative evaluation (e.g., unclear, illogical),16 positive evaluation (e.g., solid, feasible),16 research (e.g., productivity, grant),16,22,24,39 and standout adjectives (e.g., exceptional, outstanding).16,22,24,39

Our program yielded two outcome variables: binary indicators representing whether (= 1) or not (= 0) any word(s) from a category occurred in a critique and subsection; and the percent of words from each word category in each critique and subsection. These outcomes provided information about whether or not reviewers chose to use a certain category of words; and, if so, to what extent they used words from that category in critiques and subsections.40–42 To test our hypothesis that text analysis outcomes would differ significantly by PI sex with the greatest difference for male and female PIs’ R01 renewal applications, we submitted the two outcome variables for each critique and subsection as dependent variables to logistic, and OLS regression, respectively;40–42 with PI sex (M vs. F), application type (Type1/new vs. Type 2/renewal), and the interaction effect between PI sex and application type as predictor variables. Models used standard errors clustered at the applicant level; adjusted for experience level (new vs. experienced investigator), funding outcome (unfunded vs. funded) and interactions between PI sex and experience level, and PI sex and funding outcome; and controlled for priority score [See Supplemental Digital Appendices 1 and 2 [LWW INSERT LINK] for coefficients (and standard errors)]. Significance levels for all statistical tests were set at the 0.05 level. We performed statistical analyses using STATA software (release version 14; College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2015).

The University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) Institutional Review Board approved all facets of this study.

Results

Analyses of priority and criteria scores

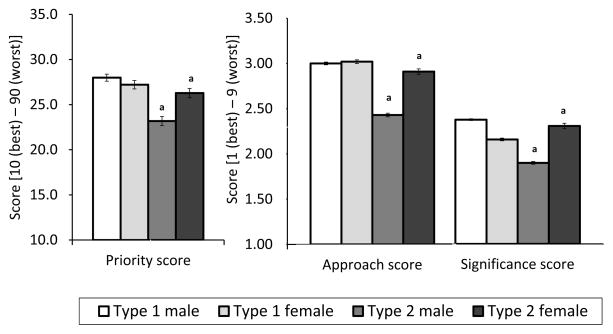

From 224 of 241 Summary Statements (93%), 218 priority scores and 680 criteria scores were available. Regression models showed significant two-way interactions between applicant sex and application type for priority (b = .19, SE = .09, P < .05), approach (b = .21, SE = .10, P < .05), and significance (b = .27, SE = .10, P < .01) scores (Table 1). Examination of these effects showed no difference in scores for male and female PIs’ Type 1 applications but significantly worse (higher) scores for female than male PIs’ Type 2 applications (P < .05 for all comparisons; Figure 2).

Table 1.

Coefficients (and Standard Errors) for Regression of Priority Score and Each Criteria Score on PI Sex, Experience Level, R01 Type, Funding Outcome, and PI Sex Interactions, From a Study of 739 NIH R01 Grant Critiques and Scores, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Fiscal Years 2010–2014a

| Priority score (n = 218) | Approach score (n = 680) | Significance score (n = 680) | Innovation score (n = 679) | Investigator score (n = 680) | Environment score (n = 679) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI sex | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.04 (0.08) | −0.04 (0.09) | 0.09 (0.09) | 0.21b (0.09) | 0.04(0.07) |

| R01 type | −0.15b (0.07) | −0.17c (0.06) | −0.18c (0.07) | −0.12 (0.07) | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.05(0.05) |

| PI sex × R01 type | 0.19b (0.09) | 0.21b (0.10) | 0.27c (0.10) | 0.19 (0.12) | −0.09 (0.09) | 0.03 (0.08) |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.46 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.07 |

Abbreviations: NIH indicates National Institutes of Health; PI, primary investigator.

Variables are coded as follows: PI sex, M = 0, F = 1; R01 type, Type1/new project = 0, Type 2/renewal = 1; Models adjusted for experience level, funding outcome, and interactions between all variables. All scores were transformed to logarithmic scale to address skew. Priority scores (n = 218) at NIH range from 10 (best) to 90 (worst) and are modeled at the application Summary Statement level—due to sample size restraints this model did not adjust for interactions between PI sex and experience level and PI sex and funding outcome; Criteria scores (n = 680) at NIH range from 1 (best) to 9 (worst) are modeled at the critique level—these models adjusted interaction effects between PI sex and experience level, and PI sex and funding outcome; Significant negative coefficients for main effects indicate better (i.e., lower) scores for the group coded as 1; significant positive coefficients for main effects indicate better (i.e., lower) scores for the group coded as 0. The positive coefficients for the interaction effects between PI sex and R01 type indicate that female PIs’ type 2 grants were assigned higher (i.e., worse) scores than those of males.

Difference between groups is significant at the P < .05 level.

Difference between groups is significant at the P < .01 level.

Figure 2.

Estimated priority, approach, and significance scores assigned to male and female investigators’ Type 1 and Type 2 applications, from a study of 739 NIH R01 grant critiques and scores, University of Wisconsin-Madison, fiscal years 2010–2014. Priority scores [scale: 10 (best) to 90 (worst)] are modeled at the application summary statement level; N = 218; due to sample size restraints this regression model did not adjust for interactions between PI sex and experience level and PI sex and funding outcome. Criteria scores [scale: 1 (best) to 9 (worst)] are modeled at the critique level; N = 680; here, regression models also adjusted interaction effects between PI sex and experience level, and PI sex and Funding outcome.

Abbreviations: NIH indicates National Institutes of Health; PI, primary investigator.

aDifference between groups is significant at the P < .05 level.

To examine the association between criteria and priority scores, we regressed priority scores on criteria scores (Table 2). Approach scores predicted priority scores for all PIs’ applications (b = .62, SE = .06, P < .001), suggesting that having a strong (low) approach score was most important for earning a strong (low) priority score. Analyses within application type showed that the weight of the approach score in predicting the priority score was significantly larger for female than male PIs’ Type 2 applications (P < .05; Table 2). Only for female PIs’ Type 1 applications did significance scores also predict priority scores (b = .38, SE = .12, P < .01), but there were no scoring disparities for male and female PIs’ Type 1 applications.

Table 2.

Coefficients (and Standard Errors) for Regression of Priority Scores on Criteria Scores Assigned to Male and Female PIs’ Type 1 and Type 2 R01 Applications, From a Study of 739 NIH R01 Grant Critiques and Scores, University of Wisconsin- Madison, Fiscal Years 2010–2014a

| All (n = 217) | Type 1 | Type 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 86) | Female (n = 61) | Male (n = 45) | Female (n = 25) | ||

| Approach | 0.62b (0.06) | 0.72b (0.09) | 0.55b (0.11) | 0.42c (0.14) | 1.06c (0.27) |

| Significance | 0.26b (0.06) | 0.21 (0.11) | 0.38c (0.12) | 0.30 (0.15) | 0.16 (0.14) |

| Innovation | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.09) | 0.12 (0.09) | 0.20 (0.13) | −0.09 (0.12) |

| Investigator | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.04 (0.10) | −0.05 (0.09) | −0.07 (0.09) | −0.10 (0.19) |

| Environment | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.19 (0.13) | 0.12 (0.11) | 0.07 (0.15) | −0.04 (0.18) |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.72 |

Abbreviations: NIH indicates National Institutes of Health; PI, primary investigator.

Models adjusted for experience level, funding outcome, and interactions between these variables. NIH priority scores (n = 218) range from 10 (best) to 90 (worst), and criteria scores (n = 680) range from 1 (best) to 9 (worst). Criteria scores were averaged across critiques within an application Summary Statement because priority scores are assigned at the application level, but criteria scores are assigned at the critique level (~3 per application); Significant positive coefficients for scores indicate that better (i.e., lower) criteria scores are associated with better (i.e., lower) priority scores.

Difference between groups is significant at the P < .001 level.

Difference between groups is significant at the P < .01 level.

Quantitative text analysis

Whole critiques

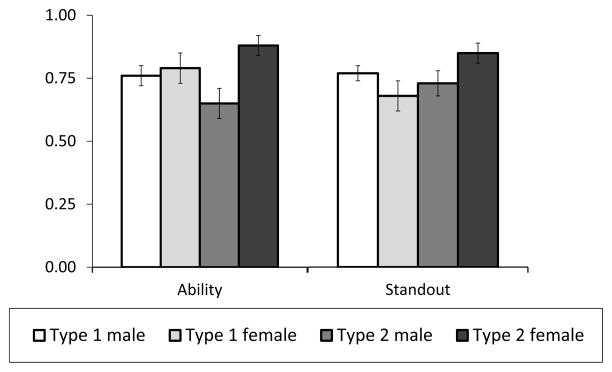

Models showed a main effect of PI sex for positive evaluation words (b = −.10, SE = .04, P < .05) and standout adjectives (b = −.20, SE = .07, P < .01), indicating a significantly higher percentage of words from these categories in critiques of male PIs’ applications (Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 [LWW INSERT LINK). Interaction effects between PI sex and application type for standout adjectives (b = 1.24, SE = .50, P < .05) and ability words (b = 1.21, SE = .47, P < .05; Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 [LWW INSERT LINK]) showed different patterns in critiques of Type 1 compared to Type 2 applications: relative to the slight differences in critiques of male and female PIs’ Type 1 applications (Figure 3), markedly more critiques of female than male PIs’ Type 2 applications contained words from the ability and standout adjectives categories Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 [LWW INSERT LINK]).

Figure 3.

Estimated probability that word(s) from the ability and standout adjectives categories will occur in critiques of male and female PIs’ Type 1 and Type 2 applications, from a study of 739 NIH R01 grant critiques and scores, University of Wisconsin-Madison, fiscal years 2010–2014. Multiplying probabilities by 100 indicates the estimated percentage of critiques in which ability words and standout adjectives are used; N = 670 critiques; regression models adjusted for experience level, funding outcome, priority score; and interaction effects between PI sex and experience level, and PI sex and funding outcome.

Abbreviations: PI indicates primary investigator; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Criteria subsections

We explored which subsections contributed to linguistic differences in whole critiques. Results showed that differences originated from the strengths subsections of the approach and significance criteria in critiques of funded applications.

Tests for non-response bias

The proportion of male and female PI participants in our sample closely resemble their proportions in our population: males make up 68% (188/278) of UW-Madison R01 PIs from 2010–14 and 61% (76/125) of participants; and females make up 32% (90/278) of R01 PIs and 39% (49/125) of participants. However, because a slightly higher percentage of female than male PIs participated, we tested for the possibility of non-response bias by modeling our data using propensity scores (i.e., the probability of a given PI’s participation conditional on observed baseline characteristics), and inverse probability weights with additional auxiliary variables (which penalizes oversampled groups).43–47 Results from these models did not substantially differ from our reported findings. Taken together, these analyses provide evidence to suggest that our findings are not attributable to different patterns of participation for male and female PIs.

Discussion

In line with our hypothesis, we identified subtle but significant differences in reviewers’ scores and critiques for male and female PIs’ R01 applications, with the greatest differences for Type 2 applications. Results point to three major findings.

First, female PIs applying for Type 2 R01s may be disadvantaged in scoring: results showed worse (higher) priority, approach, and significance scores for female than male PIs’ Type 2 applications (Table 1, Figure 2). Although approach scores predicted priority scores for both male and female PIs’ Type 1 and Type 2 applications (Table 2), regression weights were highest for female PIs’ Type 2 applications. This suggests that receiving an uncompetitive (high) approach score may have been more detrimental for these female PIs than for any other group.

Next, text analysis results from whole critiques suggest that reviewers may have held male and female PIs of Type 2 applications to different evaluative standards: markedly more critiques of female than male PIs’ Type 2 applications contained words from the standout adjectives and ability categories (Figure 3).

Finally, text analyses of subsections showed that linguistic differences in whole critiques originated in the strengths subsections of the approach and significance criteria for funded applications, which suggests these criteria may be most important for determining funding outcomes, particularly for renewals.

Findings from our study showing inconsistences in scoring and critiques for male and female PIs’ R01 applications, particularly for renewals, may be reflective of objective differences in the quality of the work applicants proposed. However, if male PIs with Type 2 applications had outperformed female PIs, as their stronger priority, approach, and significance scores would suggest, one might expect to see evidence of this across all forms of evaluation. This was not the case. Critiques of female PIs’ Type 2 applications were linguistically stronger, more often containing standout adjectives and words about ability.

It is also possible that our findings are a consequence of male and female PIs working in different research areas, but we found no evidence to support this. Similar proportions of male and female PIs proposed clinical research, and applications were reviewed across 103 study sections and funded by 21 NIH ICs, with no systematic patterns for male and female PIs. Thus, both male and female PIs in our sample were engaged in a similarly diverse range of clinical, basic, and behavioral research projects spanning multiple fields. We did not find evidence of non-response bias, suggesting that our findings are reflective of R01 PIs at UW-Madison. Because there are similar criteria for hiring, promotion, and productivity for all UW-Madison faculty, male and female PIs would be expected to have similar background qualifications. Further support that male and female PIs in our sample had similar qualifications and productivity levels comes from the absence of any significant differences in scoring and critiques of the investigator criterion section of their proposals in which reviewers evaluate the PI’s qualifications, productivity, and achievements.48 For such a relatively homogenous sample of male and female applicants, what could explain contrasting scores and critiques for Type 2 applications?

Our findings most strongly align with a large body of work spanning the past 30 years regarding the impact of gender stereotypes on evaluative judgments. This broad array of theoretically grounded experimental and observational studies show that stereotype-based beliefs that women lack the agentic traits (e.g., independence, leadership ability, logic, strength) associated with ability in male-typed domains like science can lead reviewers to doubt women’s competence. 9,10,14,15,19 This type of bias is often unconscious, occurs despite explicitly held egalitarian beliefs, and most directly impacts those with a strong belief in their own objectivity (e.g., scientists).19,21,31,32,49 Such bias is most likely to occur when a review is for a high-status position or award (as leadership and mastery are highly agentic),11,15,50 and is tenacious. For example, Kawakami et al. found that pro-male bias in leader selection persisted even with counterstereotype training.51

Compared to first R01s, renewals are higher status awards in a male-typed field (science52), and applicants are judged by criteria that align with leadership as they are required to have “an ongoing record of accomplishments that have advanced their field(s)”.48 Taken together, experimental studies would predict that these factors would heighten the salience of an applicant’s sex and lead reviewers, however unconsciously and inadvertently, to more easily judge female PIs as less competent than male PIs to lead Type 2 R01s.

Depending on the nature of a review process, and the type of criteria used to evaluate applicants, such stereotype-based gender bias can surface in different ways.9,15 For example, experiments in the realm of status characteristics theory by Biernat and Kobrynowicz,10 Foschi,14 and Heilman and Haynes15 have shown that assumptions that women are less competent than men can lead reviewers to hold women to higher ability standards by requiring them to have higher quality work or more prior achievements.14,15,53 This research would suggest that more laudatory commentary in critiques of female PIs’ Type 2 applications in our sample could be evidence that female PIs needed higher quality applications than male PIs to earn scores in the fundable range.53 Another possible explanation for our results comes from studies by Glick and Fiske showing that implicit beliefs that women are less competent than men are confounded by perceptions that women are weak and need to be protected from negative experiences.54,55 Consequently, reviewers may give women worse numerical ratings, but “soften the blow” with faint praise and positive remarks. Although this could explain worse scores and stronger critiques for female than male PIs’ Type 2 applications in our sample, this interpretation is unlikely because so called “ambivalent sexism” is most likely to occur when raters hold explicit personal beliefs about gender stereotypes, which is increasingly uncommon.54–56

More consistent with our findings of worse scores and stronger critiques for female than male PIs’ Type 2 applications is a body of research that documents the co-occurrence of more positive linguistic comments and poorer numerical rankings for women than men in male-typed roles.10,12,13,17,20,25,28,57,58 One such study by Biernat et al. analyzed performance evaluations for attorneys in the high-status male-typed field of finance law: Women received more praise in written evaluations but worse numerical ratings, which mattered most for promotion to partner.57 Broadly, this body of research shows a pattern of in-group bias where members of a positively-stereotyped in-group (e.g., men, Whites) receive favorable ratings on criteria (i.e., scores) that matter most for obtaining tangible rewards (e.g., raises, awards) and members of a negatively-stereotyped out-group (e.g., women, ethnic/racial minorities) receive favorable ratings on criteria that matter least (e.g., written commentary, verbal praise).10,12,13,17,20,25,28,57,58 With respect to gender, such bias is most likely to operate when women make up less than 25% of applicants.59–61 Although women make up over 25% of applicants for Type 1 R01s, they are under 25% for Type 2 R01s.3,6,7 Taken together this research would predict that the conditions under which male and female PIs’ Type 2 R01s are evaluated could disadvantage female R01 renewal applicants in scoring—which matters most for determining funding outcomes—despite strong critiques, which are less consequential.9,10,14,15,22,24,58,62

Linguistic findings from this study closely replicate results from our study of R01 outcomes from applications reviewed at NIH in 2008, which showed significantly higher levels of standout adjectives, and greater reference to ability and competence in critiques of female than male PIs’ Type 2 applications.16 In that study, however, we found no scoring disparities, raising the possibility that the new review format may somehow contribute to scoring disparities for male and female R01 renewal applicants. Overall, our current findings suggest that despite the changes implemented in 2009, gender bias may continue to operate in NIH’s peer review process to disadvantage female R01 renewal applicants, and that text analysis may be an effective way to probe for this bias. 16

Our study has limitations. The observational design limits any assertion of causality: Even though we attempted to rule out non-responder bias and selection bias in several ways, it is possible that our findings relate to unidentified differences between male and female PIs apart from applicant sex that could account for the observed differences in scores and critiques. In addition, even though our participants were reviewed by 103 NIH study sections, funded by 21 NIH institutes, and represent 30 departments, they were all faculty at a single institution which may limit the generalizability of our findings to PIs at other institutions. Another possible limitation is that we used only 7 word categories and counts of single words. Although extending the analyses to other text analysis procedures or additional word categories might yield different results, the 7 word categories we chose were previously validated16 and single word counts are an effective and widely used text analytic technique for detecting evaluator sentiment, particularly in large corpora that cannot be feasibly hand annotated.63 Another limitation of our study is that data represent only PIs’ applications that were either funded as first submissions or as revisions; we do not have outcomes from terminally unfunded applications. The NIH keeps the identity of these applicants confidential, which prevented our access to a full range of R01 applicants to invite to participate in our study. However, our findings of disparities in critiques and scoring for male and female PIs’ applications within the fundable range provides compelling evidence for the need to examine critiques and scores for unscored applications, where bias would be very consequential. As a final limitation, the “clinical” meaning of effect sizes that are statistically significant is important to consider. In our study, effect sizes for differences in scores and critiques ranged from ~.1 to .45 (Cohen’s d). Such effect sizes have proven meaningful in social/behavioral science research.64,65

In spite of its limitations, our study has important implications. Women remain underrepresented in high ranks and leadership in academic medicine and biomedical research—positions that depend on strong records of NIH funding.1,2 If, as our study suggests, stereotype-based gender bias contributes to disparities in reviewers’ ratings of male and female PIs’ Type 2 applications, the impact could be highly consequential. For example, a simulation study by Martell et al. found that slight pro-male bias in performance ratings (e.g., 1% to 5%) significantly impacted promotion rates and left female employees underrepresented in high ranks after only a few cycles of evaluation.66 If disparities in NIH peer reviewers’ ratings similarly contribute to the lower R01 renewal award rates observed for female PIs nationally7 the magnitude of the effect on women’s representation in academic medicine could be equally detrimental. To estimate this impact we applied award rates from Ley and Hamilton’s3 study to the period between 1998 and 2014 showing lower R01 renewal award rates for female PIs.7 We estimated that ~2,000 female PIs went without renewal funding and potentially had to close their labs during that time.3,7 The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) most recent report shows that although women make up just 21% of professors they are overrepresented (56%) as instructors.1 These AAMC data show just one of the potential impacts of women’s lower R01 success rates: Women fail to advance at equivalent rates to men and are more likely to teach than remain in research careers. Because women are more likely than men to study issues within the realm of women’s health, women’s attrition from research careers perpetuates health disparities.21,67 This loss also limits the pool of research mentors for early career scientists, particularly for women who derive benefit from mentoring in multiple role management that senior women can provide.21,67,68

If future studies with experimental designs or national datasets confirm that gender bias disadvantages female R01 applicants in NIH peer review, bias reducing interventions69,70 may be useful as a part of NIH reviewer training. However, such strategies must be carefully constructed and evaluated. Simply increasing awareness of the ubiquity of stereotype-based bias has been shown experimentally to exacerbate the application of age, gender, and bodyweight stereotype-based bias.71 Conversely, either informing participants that the prevalence of stereotype-based bias is low or that most people are trying to overcome the influence of stereotypes on their evaluations of others reduced the application of gender bias compared to no message or the message about the high prevalence of stereotype-based bias.71 Building on this research, a simple intervention to study might involve randomly including such a message (e.g., “most NIH scientific peer reviewers are working hard to reduce the influence of stereotypes in their evaluation of R01s”) in the materials sent to a random sample of R01 reviewers. Analysis of the critique text and scores could be compared for reviewers in the experimental and control groups. Other strategies to reduce the salience of gender in the NIH peer review process might include replacing abstract descriptors that reinforce male stereotypes (e.g., high-risk, independent) with more concrete and less gender-valenced language (e.g., “research with the potential to change the direction of current investigation,” “an investigator who has been the principal investigator on a grant proposal or supervised graduate students”).11,50,72

Findings from this study raise the possibility that despite the NIH’s alterations to its peer review system in 2009, stereotype-based gender bias may continue to operate in the review process. Because female applicants for R01 renewals may be particularly disadvantaged, future research should target reasons for applicant sex disparities in Type 2 R01 award rates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Jennifer Sheridan, Executive and Research Director, Women In Science and Engineering Leadership Institute (WISELI), UW-Madison for her help in accessing data on background characteristics for PIs in the study sample.

Funding/Support: This research was funded by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health grant # R01 GM111002.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at [LWW INSERT LINK].

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: The University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of this study. Protocol # SBS2012-1177.

Contributor Information

Anna Kaatz, Director of computational sciences, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

You-Geon Lee, Associate researcher, Wisconsin Center for Education Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Aaron Potvien, Doctoral candidate in the Department of Statistics and a researcher, Health Innovation Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Wairimu Magua, Postdoctoral research associate, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Amarette Filut, Research assistant, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Anupama Bhattacharya, Undergraduate student and data science scholar, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Renee Leatherberry, Staff researcher, Center for Women’s Health Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Xiaojin Zhu, Associate professor, Department of Computer Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Molly Carnes, Director, Center for Women’s Health Research, professor in the Departments of Medicine, Psychiatry, and Industrial and Systems Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison; and a part-time physician, William S. Middleton Veterans Hospital, Madison, Wisconsin.

References

- 1.Lautenberger O, Dandar V, Raezel C, Sloane R. The State of Women in Academic Medicine: The Pipeline and Pathways to Leadership 2013–2014. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Bridges to Independence. Bridges to Independence: Fostering the Independence of New Investigators in Biomedical Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. Identifying Opportunities for and Challenges to Fostering the Independence of Young Investigators in the Life Sciences; Board on Life Sciences; Division on Earth and Life Studies; National Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ley TJ, Hamilton BH. Sociology. The gender gap in NIH grant applications. Science. 2008;322:1472–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.1165878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of Extramural Research, National Institutes of Health. [Accessed April 19, 2016];NIH Research Project Grant Program (R01) http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/r01.htm.

- 5.Office of Extramural Research, National Institutes of Health. [Accessed April 19, 2016];Grants and Funding: New and Early Stage Investigator Policies. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/new_investigators/

- 6.Pohlhaus JR, Jiang H, Wagner RM, Schaffer WT, Pinn VW. Sex differences in application, success, and funding rates for NIH extramural programs. Acad Med. 2011;86:759–767. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821836ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institutes of Health. R01-Equivalent Grants: Success Rates, By Gender and Type of Application. [Accessed April 19, 2016];NIH IMPAC, Success Rate File. http://report.nih.gov/NIHDatabook/Charts/Default.aspx?showm=Y&chartId=178&catId=15.

- 8.Office of Extramural Research, National Institutes of Health. [Accessed April 19, 2016];Peer Review Process. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/peer_review_process.htm.

- 9.Biernat M. Stereotypes and shifting standards: Forming, communicating and translating person impressions. In: Devine P, Plant A, editors. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 45. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biernat M, Kobrynowicz D. Gender- and race-based standards of competence: Lower minimum standards but higher ability standards for devalued groups. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72:544–557. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.3.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnes M, Geller S, Fine E, Sheridan J, Handelsman J. NIH Director’s Pioneer Awards: could the selection process be biased against women? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14:684–691. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castilla EJ. Gender, race, and meritocracy in organizational careers. Am J Sociol. 2008;113:1479–1526. doi: 10.1086/588738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleveland J, Stockdale MS, Murphy KR. Women and Men in Organizations: Sex and Gender Issues at Work. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foschi M. Double standards in the evaluation of men and women. Soc Psychol Quart. 1996:237–254. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heilman ME, Haynes MC. Subjectivity in the appraisal process: A facilitator of gender bias in work settings. In: Borgida E, Fiske ST, editors. Beyond Common Sense: Psychological Science in the Courtroom. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaatz A, Magua W, Zimmerman DR, Carnes M. A quantitative linguistic analysis of National Institutes of Health R01 application critiques from investigators at one institution. Acad Med. 2015;90:69–75. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyness KS, Heilman ME. When fit is fundamental: Performance evaluations and promotions of upper-level female and male managers. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91:777–785. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madera JM, Hebl MR, Martin RC. Gender and letters of recommendation for academia: Agentic and communal differences. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94:1591–1599. doi: 10.1037/a0016539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J. Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:16474–16479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211286109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy KR, Cleveland JN. Understanding Performance Appraisal: Social, Organizational, and Goal-Based Perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine Committee on Maximizing the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering. Beyond Bias and Barriers: Fulfilling the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmader T, Whitehead J, Wysocki VH. A linguistic comparison of letters of recommendation for male and female chemistry and biochemistry job applicants. Sex Roles. 2007;57:509–514. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9291-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinpreis RE, Anders KA. The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study. Sex Roles. 1999;41:509–528. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trix F, Psenka C. Exploring the color of glass: Letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty. Discourse Society. 2003;14:191–220. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vescio TK, Gervais SJ, Snyder M, Hoover A. Power and the creation of patronizing environments: The stereotype-based behaviors of the powerful and their effects on female performance in masculine domains. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88:658–672. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waisbren SE, Bowles H, Hasan T, et al. Gender differences in research grant applications and funding outcomes for medical school faculty. J Womens Health. 2008;17(2):207–214. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenneras C, Wold A. Nepotism and sexism in peer-review. Nature. 1997;387:341. doi: 10.1038/387341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson KY. An analysis of bias in supervisor narrative comments in performance appraisal. Human Relations. 2010;63:1903–1933. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heilman ME. Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:657–674. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heilman ME, Haynes MC. No credit where credit is due: Attributional rationalization of women’s success in male-female teams. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90:905. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Devine PG. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. J Per Soc Psychol. 1989;56:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valian V. Why so slow?: The advancement of women. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nosek BA, Smyth FL, Hansen JJ, et al. Pervasiveness and correlates of implicit attitudes and stereotypes. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2007;18:36–88. [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Institutes of Health. [Accessed April 19, 2016];Side-by-Side Comparison of Enhanced and Former Review Criteria (Research Grants and Cooperative Agreements) http://grants.nih.gov/grants/peer/guidelines_general/comparison_of_review_criteria.pdf.

- 35.National Institutes of Health. [Accessed April 19, 2016];Enhancing Peer Review at NIH. http://enhancing-peer-review.nih.gov/index.html.

- 36.National Institutes of Health. [Accessed April 19, 2016];New and Early Stage Investigator Policies. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/new_investigators/index.htm.

- 37.Jagsi R, Motomura AR, Griffith KA, Rangarajan S, Ubel PA. Sex differences in attainment of independent funding by career development awardees. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:804–811. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pennebaker J, Chung C, Ireland M, Gonzales A, Booth R. The development and psychometric properties of LIWC2007. Austin, TX: LIWC Net; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isaac C, Chertoff J, Lee B, Carnes M. Do students’ and authors’ genders affect evaluations? A linguistic analysis of Medical Student Performance Evaluations. Acad Med. 2011;86:59–66. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318200561d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belotti F, Deb P, Manning WG, Norton EC. Twopm: Two-part models. The Stata Journal. 2015;15:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fletcher D, Mackenzie D, Villouta E. Modelling skewed data with many zeros: A simple approach combining ordinary and logistic regression. Env Ecol Stat. 2005;12:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papke LE, Wooldridge JM. Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401 (K) Plan participation rates. Journal Appl Econo. 1996;11:619–632. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baulch B, Quisumbing A. Testing and adjusting for attrition in household panel data. [Accessed April 25, 2016];Chronic Poverty Research Centre (CPRC) Toolkit Note. 2011 Available at: http://www.chronicpoverty.org/publications/details/testing-and-adjusting-for-attrition-in-household-panel-data.

- 44.Cuddeback G, Wilson E, Orme JG, Combs-Orme T. Detecting and statistically correcting sample selection bias. J Soc Ser Res. 2004;30:19–33. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fitzgerald J, Gottschalk P, Moffitt RA. An analysis of sample attrition in panel data: The Michigan Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Cambridge, Mass: National Bureau of Economic Research; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foster EM, Fang GY, Group CPPR. Methods for handling attrition an illustration using data from the fast track evaluation. Eval Rev. 2004;28:434–464. doi: 10.1177/0193841X04264662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller R, Hollist C. Encyclopedia of measurement and statistics. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Institutes of Health. [Accessed April 19, 2016];Definitions of Criteria and Considerations for Research Project Grant (RPG/X01/R01/R03/R21/R33/R34) Critiques. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/peer/critiques/rpg_D.htm#rpg_overall.

- 49.Uhlmann EL, Cohen GL. “I think it, therefore it’s true”: Effects of self-perceived objectivity on hiring discrimination. Org Beh Hum Dec Proc. 2007;104:207–223. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carnes M, Bland C. Viewpoint: A challenge to academic health centers and the National Institutes of Health to prevent unintended gender bias in the selection of clinical and translational science award leaders. Acad Med. 2007;82:202–206. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d939f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawakami K, Dovidio JF, van Kamp S. Kicking the habit: Effects of nonstereotypic association training and correction processes on hiring decisions. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2005;41:68–75. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nosek BA, Smyth FL, Sriram N, et al. National differences in gender–science stereotypes predict national sex differences in science and math achievement. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10593–10597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809921106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Biernat M, Collins EC, Katzarska-Miller I, Thompson ER. Race-based shifting standards and racial discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:16–28. doi: 10.1177/0146167208325195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glick P, Fiske ST. The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J Person Soc Psychol. 1996;70:491–512. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glick P, Fiske ST. An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. Beyond prejudice: Extending the social psychology of conflict, inequality and social change. 2012:70–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.King EB, Botsford W, Hebl MR, Kazama S, Dawson JF, Perkins A. Benevolent sexism at work: Gender differences in the distribution of challenging developmental experiences. J Manage. 2012;38:1835–1866. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Biernat M, Tocci MJ, Williams JC. The language of performance evaluations: Gender-based shifts in content and consistency of judgment. Soc Psychol Person Sci. 2012;3:186–192. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Biernat M, Vescio TK. She swings, she hits, she’s great, she’s benched: Implications of gender-based shifting standards for judgment and behavior. Person Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28:66–77. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heilman M. Sex bias in hiring women. Org Beh Hum Perform. 1980;26:386–395. [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Ommeren JOS, Russo G, de Vries RE, van Ommeren M. Context in selection of men and women in hiring decisions: Gender composition of the hiring pool. Psycholo Rep. 2005;96:349–360. doi: 10.2466/pr0.96.2.349-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Isaac C, Lee B, Carnes M. Interventions that affect gender bias in hiring: A systematic review. Acad Med. 2009;84:1440–1446. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6ba00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Madera JM, Hebl MR, Martin RC. Gender and letters of recommendation for academia: Agentic and communal differences. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94:1591–1599. doi: 10.1037/a0016539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pang B, Lee L. Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Found Trend Inform Retr. 2008;2:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Glass G. Primary, secondary, and meta-analysis of research. Edu Res. 1976;5:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lipsey M, Wilson D. The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment: Confirmation from meta-analysis. Am Psychol. 1993;48:1181–1209. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.12.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martell R, Lane D, Emrich C. Male-female differences: A computer simulation. Am Psychol. 1996;51:157–158. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carnes M, Morrissey C, Geller SE. Women’s health and women’s leadership in academic medicine: Hitting the same glass ceiling? J Womens Health. 2008;17:1453–1462. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Isaac C, Byars-Winston A, McSorley R, Schultz A, Kaatz A, Carnes M. A qualitative study of work-life choices in academic internal medicine. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2014;19:29–41. doi: 10.1007/s10459-013-9457-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carnes M, Devine PG, Baier Manwell L, et al. The effect of an intervention to break the gender bias habit for faculty at one institution: A cluster randomized, controlled trial. Acad Med. 2015;90:221–230. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bauer CC, Baltes BB. Reducing the effects of gender stereoytpes on performance evaluations. Sex Roles. 2002;47:465–476. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Duguid M, Thomas-Hunt M. Condoning stereotypying? How awarness of stereotyping prevalence impacts expression of stereotypes. J Appl Psychol. 2015;100:343–359. doi: 10.1037/a0037908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaatz A, Gutierrez B, Carnes M. Threats to objectivity in peer review: The case of gender. Trend Pharm Sci. 2014;35:371–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.