Abstract

Objectives

Multiple pathways link gender-based violence (GBV) to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among women and girls who use or inject drugs. The aim of this paper is to synthesize global literature that examines associations among the synergistic epidemics of substance abuse, violence and HIV/AIDS, known as the SAVA syndemic. It also aims to identify a continuum of multi-level integrated interventions that target key SAVA syndemic mechanisms.

Methods

We conducted a selective search strategy, prioritizing use of meta-analytic epidemiological and intervention studies that address different aspects of the SAVA syndemic among women and girls who use drugs worldwide from 2000–2015 using PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar.

Results

Robust evidence from different countries suggests that GBV significantly increases the risk of HIV and other STIs among women and girls who use drugs. Multiple structural, biological and behavioral mechanisms link GBV and HIV among women and girls. Emerging research has identified a continuum of brief and extended multi-level GBV prevention and treatment interventions that may be integrated into a continuum of HIV prevention, testing, and treatment interventions to target key SAVA syndemic mechanisms among women and girls who use drugs.

Conclusion

There remain significant methodological and geographical gaps in epidemiological and intervention research on the SAVA syndemic, particularly in low and middle-income countries. This global review underscores the need to advance a continuum of multi-level integrated interventions that target salient mechanisms of the SAVA syndemic, especially for adolescent girls, young women and transgender women who use drugs.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, STIs, Substance Use, Gender-based Violence, Intimate Partner Violence, Childhood Sexual Abuse, Interventions

INTRODUCTION

Gender-based violence (GBV) is a serious public health threat and human rights violation, which disproportionately affects women and girls who use or inject drugs, and significantly increases behavioral and biological risks for HIV infection. The term “GBV” incorporates prevalent forms of violence among women and girls who use drugs articulated in the UN General Assembly Definition (1993), including childhood sexual abuse (CSA), intimate partner violence (IPV), non-partner sexual assault and trafficking.1 Worldwide, women and girls who use drugs experience routine structural forms of GBV from police, prison guards and custodial care.2,3 WHO estimates that more than 30% of women and girls worldwide experience physical or sexual violence from intimate partners and about 7% experience sexual assault from non-partners.4 For women and girls who use drugs, such population-level prevalence estimates are scarce. However, research among clinical and community-based samples of women who use drugs has estimated that between 20% and 57% have experienced IPV in the past year,5,6 which is 2 to 5 times higher than the prevalence rates found among general female populations.6,7 Women who use drugs or alcohol also experience substantially higher rates of sexual assault from non-intimate partners, including drug dealers, pimps, commercial clients and police, than found among general female populations.2,3,8

Multiple pathways link GBV to HIV among women and girls who use drugs. The onset of risky sexual behaviors and substance use disorders (SUDs), which include misuse of drugs and/or alcohol, and risky sexual behaviors may be triggered by CSA, GBV or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) associated with GBV. At the same time, women and girls with SUDs are at heightened risk of experiencing GBV as well as of acquiring HIV. A growing number of researchers have conceptualized the synergistic interactions found among the epidemics of substance abuse, GBV, and HIV/AIDS as the SAVA syndemic.9–12

The SAVA syndemic was first defined by Singer (1994) as the “set of closely intertwined and mutual enhancing epidemics” of substance abuse, violence and HIV, which are reciprocally influenced and sustained by the larger risk environment and the broader set of power relations shaped by gender, race/ethnicity and class.10,11 These inextricably linked epidemics are synergistically reinforced by multiple behavioral, biological and structural mechanisms.

This paper aims to review and synthesize global literature that examines the syndemic effects of the most pervasive forms of GBV (i.e., IPV and non-partner sexual violence) among women and girls who use drugs on: 1) engaging in HIV risk behaviors; 2) acquisition and transmission of HIV and STIs; 3) GBV-related trauma that results in PTSD and further heightens risk for revictimization and HIV; and 4) access to HIV testing, treatment and anti-retroviral (ART) medication adherence. We also identify a range of evidence-based GBV prevention and treatment models that may be integrated with a continuum of HIV interventions to address key SAVA syndemic mechanisms.

METHODS

Our literature search strategy is selective rather than exhaustive, prioritizing use of meta-analytic studies and recent studies that have targeted epidemiology and interventions addressing different aspects of the SAVA syndemic among women and girls who use drugs worldwide from 2000–2015 using PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar. A search strategy was conducted that included combinations of the following key search terms in English: women, girls, HIV, AIDS, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) sexual risk behavior, condom use, substance use/abuse, injection drug use, heroin/cocaine use, alcohol/binge drinking, marijuana, GBV, sexual violence/assault, intimate partner violence/abuse, domestic violence, CSA, forced/coerced sex, trafficking, PTSD, SAVA, antiretroviral medication adherence, screening, intervention, treatment, services, HIV prevention, HIV counseling and testing (HCT), harm reduction services. Eligible articles addressed at least two terms representing key aspects of the SAVA syndemic (Substance use, HIV/AIDS, Violence, PTSD/Trauma). We also included additional references from seminal articles and searched databases of WHO, UNAIDS, UNODC and CDC for relevant literature. Seminal articles were selected by geographic representation, sample size, methodological rigor of the study, and citation index factor. Our search focused on violence victimization among women, not perpetration of violence. The first four co-authors conducted literature searches and independently screened titles and abstracts of studies to assess their eligibility for inclusion. All authors reviewed the selected studies and participated in decisions about inclusion of studies in cases of uncertainty. This search strategy yielded 75 articles that were included in this review.

RESULTS

Syndemic Mechanisms Linking Substance Use, GBV, Trauma and HIV

Meta-analyses suggest that the relationship between GBV and substance use among women and girls is bi-directional and complex, varying by type of substance, by whether one or both partners are under the influence of drugs or alcohol, by type of violence and by mutuality of violence.5,7 Cocaine and alcohol use have consistently had the largest effect sizes on women’s experience of IPV.5 Studies indicate strong associations between alcohol and cocaine use and forced sex among women and girls.13,14 Forced sex also has been found to increase the likelihood of sexual violence revictimization.13

Multiple structural, biological and behavioral syndemic mechanisms link drug use and sexual violence to HIV. Substance-using venues (e.g., bars, shooting galleries) have been linked to aggressive sexual behaviors and HIV risks.15,16 The psychopharmacological effects of some substances (e.g., cocaine and alcohol), which lower levels of serotonin, may increase the likelihood of aggression and impair judgment and ability to recognize cues and fend off sexual violence for women under the influence.8 Other drugs, such as heroin and benzodiazepines, are used to cope with the pain and stress from GBV,5 further heightening their risk for revictimization and HIV. Substantial research has established strong relationships between substance use and transmission of HIV17 as well as between substance use and lack of access to HIV care and poor medication adherence.12,14

Research has documented salient syndemic GBV-related risks for HIV transmission through both unsafe injection and sex among women and girls who inject drugs.18 Large clinic and population-based studies in the U.S. demonstrate that experience of IPV is associated with adolescent girls’ and women’s own injection drug use, their partner’s injection drug use, as well as other sexual risks, including exchanging sex for money and drugs, unprotected anal sex, and STIs.18,19 Furthermore, research has found associations between sexual violence and receptive syringe sharing.20,21

Accumulating research worldwide has documented a robust association between experiencing different types of GBV and HIV infection, which is magnified among women and girls who use drugs.22 To date, this research has largely remained geographically clustered in the U.S. and sub-Saharan Africa which has the highest HIV prevalence in the world, alongside IPV prevalence rates of 42–66% in some regions.4 There remains a lack of research on how the syndemic is playing out among women and girls who use drugs in many low- and middle-income countries, particularly in some Asian and Central European countries with injection-driven epidemics.

Although physical IPV is not a direct mechanism for HIV transmission, a recent meta-analysis of global data documents that physical IPV alone increases risk for HIV by 28–52% among different populations of women, including some substance-using women.4,22 Physical IPV may create a context of fear and submission that makes it difficult for women to negotiate safer sex, particularly if they are under the influence of drugs or alcohol, and for HIV-positive women to disclose their HIV status. Growing research further suggests that experiencing physical and other types of IPV and GBV increases the likelihood of not getting tested for HIV as well as not accessing and staying in HIV care and poor ARV medication adherence among women who use drugs.12,23

Psychological IPV may also instill fear and submission in women, heightening their risks for HIV and preventing disclosure of HIV and STIs.24 Research on the relationship between psychological IPV and HIV remains scarce, particularly among substance-using women, and has not been as rigorous. The lack of a standardized definition of psychological IPV, which may varyingly include verbal, controlling, isolating and dominating behaviors, as well as the large overlap between physical and psychological IPV and the failure to isolate the effects of psychological IPV have impeded research efforts.24 To address these challenges, a recent study found that verbal IPV was significantly associated with incidents of HIV infection among a population-based longitudinal cohort of women in Rakai, Uganda, exerting similar effects to physical and sexual IPV.25

Sexual IPV was reported more often as an independent risk factor for HIV infection among women than any other form of IPV in a recent meta-analysis.22 Biologically, the risk of HIV acquisition increases during forced sex with HIV-positive partners due to vaginal and anal lacerations, particularly in adolescent girls,26 innate and adaptive immune system changes of the vaginal and cervical mucosa in the female reproductive tract across the lifespan,27 and an altered stress response that can interact with pro-inflammatory responses.26,28

Indirectly, forced sex and HIV/STIs are linked through risky sexual and drug-related behaviors, trauma-related symptoms (PTSD and depression) and CSA.22,26,28 CSA may play a catalytic role in driving the SAVA syndemic. CSA is a strong risk factor for substance use, particularly injection drug use,29 engaging in risky sex,30 HIV acquisition,30 and failing to engage in HIV care and medication adherence.12,23 Research suggests that CSA is the type of trauma most closely associated with PTSD symptoms among women.31 PTSD prevalence estimates among women with GBV histories range between 31–84%, significantly higher than rates found among women in the general population.23 PTSD is also strongly associated with substance use32 as well as with having multiple partners, inconsistent condom use, STIs,33 and poor medication adherence.34

The forced sex-HIV/STI relationship is particularly salient among female sex workers (FSWs) and women and girls who are coerced into sex work. Women may be pressured by their partners to engage in sex work in order to pay for drugs for both of them.35 Among FSWs, forced sex is associated with inconsistent condom use and HIV infection.36 Those trafficked into sex work are at increased risk for HIV due to high exposure to sexual violence, substance use, and unprotected sex with multiple partners.37

High rates of police violence against women who use drugs have been documented around the world, particularly among FSWs. A U.S. study of 318 women recruited from drug courts found that 31% reported rape by an officer.2 Police violence is of particular concern since police are often first responders to GBV incidents, and they play an instrumental role in facilitating legal protections from abusers and prosecution of GBV as well as ensuring safe access to harm reduction programs and HIV services.

Addressing the SAVA Syndemic with a Continuum of Integrated Interventions

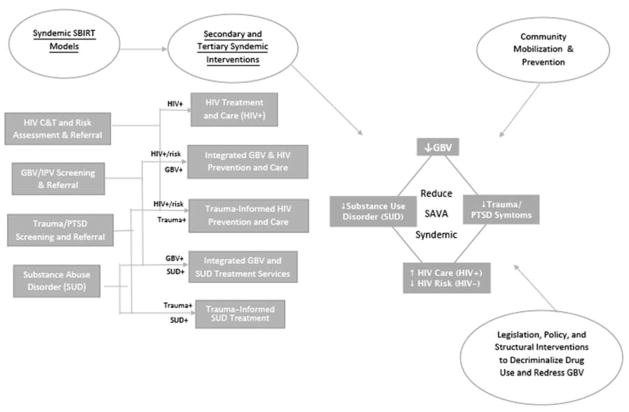

The heuristic value of the SAVA syndemic conceptual framework is its focus on identifying the specific behavioral, biological and structural mechanisms that can be modified by a continuum of multi-level integrated interventions or policies (see Figure 1). This continuum includes 1) IPV screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment and services (SBIRT) models that may be integrated with HIV counseling and testing (HCT); 2) integrated behavioral IPV and HIV prevention interventions 3) extended trauma-informed integrated treatments to prevent HIV or promote medication adherence and 4) primary prevention community-level or structural models.

Figure 1.

Continuum of Integrated GBV and HIV Interventions to Address SAVA Syndemic among Women & Girls Who Use Drugs

IPV SBIRT models and integrated interventions for women and girls who use drugs

Emerging research worldwide suggests that IPV SBIRT models, which include IPV screening, safety planning, advocacy, and referrals to IPV services, may reduce HIV risks for women in health care settings (see Table 1).38,39 A recent systematic review39 of six IPV SBIRT models that met evaluation criteria for women in health care settings identified two studies associated with reduction of physical IPV;39–41 however, neither model focused on women who use drugs. A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) that tested the effectiveness of a single-session computerized versus case manager-delivered SBIRT models (WINGS) among 191 substance-using women in probation settings in the U.S. found that both modalities identified equally high rates of having experienced any physical and sexual IPV in the past year (47% for both conditions), and both modalities significantly reduced drug use at the 3-month follow-up and increased use of IPV services.42

Table 1.

Continuum of evidence-based Interventions that have demonstrated positive effects on two or more SAVA outcomes

| Intervention & Publication(s) | SAVA Components in Intervention | Summary of Intervention | Target Population | Location of study | Study Details | Study Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPV SBIRTs: | ||||||

| WINGS Gilbert et al. (2015) | Substance use, IPV | Psychoeducation on IPV, IPV screening, safety planning, social support enhancement, goal-setting | Substance-using women under community supervision | New York City, USA | RCT with 191 substance-involved women under community supervision in US; computerized (one 45-minute self-paced session) vs traditional (one 45-minute group session led by case manager) modalities | Identified high rates of IPV in both groups; decrease in drug use from baseline to three-month follow up; computerized self-paced participants reported greater social support enhancement; case manager-delivered intervention participants reported greater linkage to services |

| Tiwari et al. (2005); Parker et al. (1999) | IPV | Empowerment training | Pregnant women with a history of IPV | USA | Tiwari et al: RCT with 110 women (empowerment intervention group vs standard treatment) 30-minute individual counselling with counselor Parker et al.: RCT with 199 women (empowerment group vs standard treatment); three 30-minute individual counseling sessions | Tiwari et al: Intervention group reported significantly greater decrease in psychological and minor physical abuse and incidences of post-natal depression Parker et al: Intervention group reported decrease in violence at 6 and 12 month follow-ups |

| Integrated IPV and HIV Behavioral Prevention Interventions: | ||||||

| WORTH - Women on the Road to Health El-Bassel et al. (2014) | IPV, HIV | Social cognitive, behavioral, sexual negotiation and safety skills, IPV screening, safety planning and referrals | Drug-involved women on probation | New York City, USA | RCT with 306 drug-involved women; multimedia, traditional intervention & control groups; 4 (120 minutes) group sessions | Intervention groups (both multimedia and traditional) reported decrease in risk behaviors (increase in protected sex acts, decrease in unprotected sex acts) |

| Wechsberg et al. (2006) | HIV, substance use, violence | Women-focused; | Women | South Africa | RCT with 90 women; women-focused vs standardized groups | Both intervention and control reported decrease in risk behavior (unprotected sex); treatment reported decrease in daily use of alcohol/cocaine, and decrease in violence (number of incidences) |

| HIV risk reduction education Kalichman et al. (2008) | HIV, alcohol abuse | Risk reduction program for HIV and alcohol; skills-based training for negotiation | Men and women recruited from informal alcohol-serving establishments | South Africa | RCT with 353 men and women; one (3 hour) session for treatment group vs one (1 hour) educational session for control | Intervention group reported decrease in risk behaviors (unprotected sex, number of partners, less alcohol use prior to sex) |

| Sikkema et al. (2010) | HIV and IPV | HIVRR intervention for IPV survivors | Women who are survivors of IPV recruited from trauma services NGO | USA | 97 women assigned to one of two types of the intervention; 6-session intervention and one-day intervention | Both groups reported improved HIV knowledge and decrease in trauma symptoms, greater condom use self-efficacy; 6-session group showed greater improvement in HIV knowledge |

| Evidence-based trauma-informed interventions: | ||||||

| Emotional Disclosure Intervention Ironson et al. (2013) | PTSD, HIV | Narrative exposure, cognitive processing, emotional disclosure | HIV+ and experienced childhood abuse | USA | RCT with 244 HIV+ male & female participants; intervention group (trauma writing) vs control group (daily events writing); 4 (30 min) individual essay writing sessions | Women in intervention group showed significant reduction in PTSD, depression and HIV symptoms; no effect for men |

| Healing Our Women Program Chin et al. (2014); Wyatt et al. (2011) | Childhood abuse, PTSD, HIV | Cognitive-behavioral, integrated | HIV+ and experienced childhood abuse | USA | Wyatt et al. (2011): RCT with 147 HIV+ women; intervention (immediate treatment) vs control (delayed treatment; 11 (90 min) group sessions Chin et al. (2013): same study population, studied differences in outcomes among participants | Wyatt et al. (2011): Intervention subjects reported decrease in PTSD symptoms, decrease in psychological distress Chin et al. (2013): Higher trauma burden associated with greater reduction in psychological distress |

| Helping to Overcome PTSD with Empowerment (HOPE) Johnson et al. (2011) | IPV & PTSD | Psychoeducation, cognitive, behavioral, interpersonal | Women experiencing IPV, PTSD, shelters | USA | RCT with 70 women; intervention vs control (standard services); 9 to 12 (90 min) individual sessions | Intervention group significantly less likely to have experienced reabuse at 6-month follow-up |

| Living in the Face of Trauma (LIFT) Sikkema et al. (2013); Meade et al. (2010) | CSA, HIV, traumatic stress, substance abuse | Integrated, cognitive, behavioral | HIV+ & childhood abuse | New York City, USA (urban community) | Sikkema et al. (2013): RCT with 247 men and women in the US; coping group vs support group (control); 15 (90 min) group sessions Meade (2010): same study population | Sikkema et al., 2013: Intervention group reported greater reduction in traumatic stress compared to control Meade et al. (2010): Intervention participants reported greater decrease in both alcohol and cocaine use |

| Relapse Prevention and Relationship Therapy Gilbert et al. (2006) | substance abuse, violence | relapse prevention, relationship | IPV & SUD | New York City, USA (urban community) | RCT with 34 women in the US; relapse prevention vs informational control group; 12 (120 min) individual & group sessions | Intervention participants more likely to report decrease in minor physical, sexual, psychological IPV and severe psychological IPV, more likely to report decrease in drug use |

| Seeking Safety (SS) Najavits (2002); Hien et al. (2010) | substance abuse, PTSD, HIV | integrated, cognitive behavioral, problem-oriented | PTSD, trauma, SUD | USA | Hien et al. (2010): RCT with 353 women; Seeking Safety vs. women’s health education (control); 25 (60–90 min) individual & group sessions | Hien et al. (2010): intervention group showed decrease in HIV sexual risk behaviors (# of unprotected sex acts) |

| Trauma Recovery and Empowerment (TREM) Amaro et al. (2007) | PTSD, mental disorders (including SUDs), HIV | skill development, trauma processing | women, trauma & SUD | USA | RCT with 232 women; TREM intervention vs standard treatment (control); 25 (60 min) group sessions | Intervention group was less likely to engage in risk behaviors (unprotected sex) |

| Community mobilization & structural interventions: | ||||||

| SASA Abramsky et al. (2014) | HIV and IPV | Community-level mobilization intervention to prevent and raise awareness of GBV through local activism, media, advocacy | Communities | Kampala, Uganda (urban communities) | Cluster randomized controlled trial; Men and women in 4 treatment and 4 control clusters; community members randomly sampled to assess outcomes, with 1,583 participants at baseline and 2,532 participants at the four-year follow-up | Intervention clusters reported lower acceptance of IPV among both men and women, higher acceptance that women can refuse sex, lower past year experience of both physical and sexual IPV among women, women more likely to receive support |

| SHARE Wagman et al. (2015) | IPV, HIV | Integrated IPV prevention and HIV services, community mobilization intervention | Men and women, communities | Rakai District, Uganda (rural communities) | Community-level mobilization intervention; 11,448 individuals in 4 treatment and 7 control clusters | Intervention clusters reported decrease in incidences of physical and sexual IPV; at 2-year follow-up reduction in HIV incidence in intervention clusters |

| Stepping Stones Jewkes et al. (2008) | HIV, IPV | Participatory learning, risk reduction, single-sex sessions | Communities | Eastern Cape, South Africa (rural communities) | Cluster randomized controlled trial; 70 villages (clusters) of 2,776 men and women aged 15–26; 13 3-hour long single-sex session + community meetings | Intervention clusters had 33% reduction in HSV-2 incidence, reduction in IPV perpetration |

| IMAGE Pronyk et al. (2006); Pronyk et al. (2008) | HIV, IPV | Microfinance Program for adult women with an HIV and IPV educational intervention | 3 target cohorts: women (who received loans), members of their households and members of the communities where they lived | South Africa (rural communities) | Pair-matched community RCT; women in intervention villages received loans, biweekly loan meetings; 860 women enrolled in loan program (or in matched control program), their families and communities | Pronyk et al. (2006): those who received intervention reduced IPV experienced by 55%; Pronyk et al. (2008): at 2 year follow-up, women in treatment group had higher access to services (VCT), more risk communication, and fewer risk behaviors (unprotected sex) |

The evidence base for behavioral IPV or GBV prevention interventions remains small, especially as compared to HIV intervention research. A recent worldwide meta-analysis of RCTs testing the efficacy of different interventions to reduce IPV among women identified only 12 RCTs that met evaluation review criteria. Several of these significantly reduced physical IPV, but none had an effect on sexual IPV.43 All of these interventions were 10 or more sessions and only one44 was found to effectively reduce IPV among women who use drugs.

Integrated IPV and HIV Behavioral Prevention Interventions for Women

Emerging research, mostly conducted in the U.S. and sub-Saharan Africa, suggests that integrated behavioral IPV and HIV interventions are effective in reducing HIV risks among women experiencing IPV (see Table 1). A recent systematic review of 44 best-evidence HIV prevention interventions identified by the CDC found only five interventions that addressed IPV.38 Another review of HIV interventions that address IPV in sub-Saharan Africa45 identified three effective interventions that resulted in increasing condom use and HIV testing, and/or decreasing sexual partners.46–48 No interventions included in these systematic reviews significantly reduced any type of IPV and none focused exclusively on women or girls who use drugs. However, Women’s CoOP, an integrated HIV and sexual safety intervention was found to be effective in reducing risky sex, drug use and victimization among women who use drugs in Africa.48 Another recent RCT found that WORTH, a 4-session group-based integrated HIV and IPV prevention intervention for drug-using women under community supervision significantly reduced both unprotected sex acts and IPV, compared to an attentional control condition.49 This research suggests that relatively brief behavioral interventions have the potential to reduce syndemic risks for IPV and HIV among women who use drugs.

Couple-based approaches may improve couples’ communication and problem-solving skills to address dyadic SAVA syndemic mechanisms.50,51 Couple-based interventions have been found effective in promoting condom use, HIV testing, and medication adherence among substance-using women51 and may also be effective in reducing IPV.52

Evidence-Based Trauma-Informed Interventions that May Address the SAVA Syndemic

Over the past two decades, several extended trauma-informed interventions have been developed that target syndemic associations among substance use, CSA and other GBV, PTSD associated with GBV-related trauma, and HIV risks as displayed in Table 1. The studies included in this paper were with women and girls who may have had past histories of SUDs or may have reported incidents of CSA or GBV retrospectively. Their inclusion in this paper is to highlight the importance of addressing their current substance misuse, present incidents of violence or current PTSD from prior GBV-related traumas in intervention efforts that may ultimately enhance their ability to protect themselves and reduce their risks for HIV. Reductions in trauma symptoms have been shown to improve SUD outcomes,53 reduce revictimization,54 and reduce risky sexual behavior,55,56 suggesting that these trauma-informed treatments may optimize client outcomes.

Meta-analytic reviews and recent studies suggest that trauma-focused interventions that address SUDs, GBV (including CSA), PTSD associated with GBV-related trauma, and HIV/AIDS in an integrated, concurrent approach are more likely to succeed, to be more cost-effective, to increase medication adherence and to reduce symptoms of PTSD57,58 and are more sensitive to client needs than parallel or sequential interventions.57,59,60Seeking Safety is the most widely tested trauma-focused integrated treatment to-date (20 RCTs and pilot studies) and has been found to significantly reduce substance use and PTSD symptoms across different populations.60,61 One study of Seeking Safety also demonstrated significant reduction in unprotected sex.62 Other trauma-informed interventions for those who are HIV+ (see Table 1) have revealed significant effects in reducing substance use, decreasing PTSD symptoms and unprotected sex as well as improving medication adherence.63–66 Common treatment elements of these trauma-informed extended treatments, which consist of 10 or more sessions, include psycho-education, emotion regulation strategies, problem solving and coping skill building, and cognitive-behavioral techniques for confronting urges. With the exception of Healing our Women (HOW), few of these interventions are culturally congruent.57,58,63 Additionally, few studies have examined the efficacy of combined pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions for the syndemic,67,68 however, those studies suggest that combined interventions are clinically warranted. Evidence generally supports the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for PTSD and other trauma-related conditions, such as depression and anxiety.68

Community-level and Structural Interventions that May Address the SAVA Syndemic

To achieve a large-scale population effect in reversing key mechanisms of the SAVA syndemic, there remains a critical need for community interventions aimed at primary prevention of GBV and HIV in communities heavily affected by substance use. Community mobilization interventions employ a range of strategies (e.g., social media, advocacy campaigns) aimed at changing gender-based norms associated with GBV and HIV risk behaviors. Emerging research from RCTs conducted mostly in Africa suggest promising effects of synchronous community mobilization interventions for men and women on reducing GBV (including sexual violence), and HIV and STI incidence (see Table 1).69–72

Economic empowerment interventions may significantly reduce both GBV and HIV risks. A cluster RCT of a combined microfinance, GBV and HIV prevention intervention group (IMAGE) for women in South Africa significantly increased condom use and HIV testing at the 2-year follow-up.69,72,73 Although this trial yielded some promising effects for reducing IPV, the effects have been mixed with research suggesting that increasing assets can both decrease or increase women’s risk of IPV.69

CONCLUSIONS

Limitations

The limitations of this review stems from limitations of the systematic reviews we relied on for both the epidemiological and intervention sections. It is possible that these reviews missed studies or that there were variations in the way dimensions of intervention and key outcome findings were coded. Nor did this review include studies in other languages, which significantly limits the scope of studies reviewed for this paper. Thus, our conclusions about the SAVA dimensions and the effects of different interventions on outcomes should be considered as preliminary.

Directions for Future Research, Interventions and Policies

Although accumulating research has elucidated SAVA syndemic mechanisms, there remain significant methodological and geographical gaps in research. Some regions, including Central and South America, the Caribbean, Central Asia and Southeast Asia, remain largely or completely unrepresented in the literature. Global estimates on the use of different drugs among women suggest substantial geographic variability in types of use.74 Given this variability, there remains an urgent need for research to understand how the syndemic is playing out among women and girls in underrepresented countries, particularly in countries with injection-driven epidemics.

The lack of systematic surveillance of different types of GBV continues to impede the mapping of GBV with HIV and drug use epidemics. Most studies have focused on physical and sexual IPV and have not focused on psychological IPV or non-partner sexual assault and the broader range of GBV. As most new HIV infections are among 15–24 year olds worldwide, a greater focus on this age group is needed. Research is also urgently needed on transgender women, who are at extremely high risk for HIV, violence and substance misuse75 but remain almost invisible in the literature.

Although a continuum of evidence-based GBV interventions has emerged that may be integrated into the continuum of HIV interventions, most integrated models have not focused on women and girls who use drugs and none have resulted in reductions in unsafe injection behaviors.38 Further research is needed to identify the structural, psychopharmacological and behavioral intervention strategies that may best address the syndemic mechanisms linking different types of drug use and poly-substance use to different types of GBV and HIV risks. This research should include a focus on how biomedical prevention options of PREP and PEP may be promoted for women who are unable to negotiate condom use or safe injection with violent partners (see Figure 1).

Integrated GBV SBIRT and HIV services should employ a multi-dimensional syndemic screening protocol that may inform the optimal type and length of integrated interventions. Such protocols should include standardized screening instruments for substance use disorders, GBV and IPV and whether violence is mutual, PTSD, and HIV risk behaviors of women and their partners. SBIRT models need to consider the full range and cultural variations in the different types of GBV.

To date, the continuum of integrated interventions that address the different aspects of the SAVA syndemic remains skewed towards secondary response interventions, rather than primary prevention of GBV and HIV. Community mobilization and economic empowerment interventions also hold promise for preventing key SAVA syndemic mechanisms, but have yet to be adapted for women and girls who use drugs. Structural interventions, including legislative, policy and advocacy initiatives, are needed to redress the high rates of police abuse against women and girls who use drugs worldwide. Targeted efforts are also needed to ensure that police, prosecutors and judges are able to respond effectively to GBV cases among women and girls who use drugs. Decriminalization of drug use is critical to reducing stigma and widening access to GBV services, substance abuse treatment, harm reduction programs, and HIV testing, treatment and care.

In sum, the findings of this global review underscore the need for a comprehensive strategy to advance a continuum of multi-level integrated interventions that target salient mechanisms of the SAVA syndemic, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries.

References

- 1.UN General Assembly. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women. 85th Plenary Meeting; 20 December 1993; Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cottler LB, O’Leary CC, Nickel KB, et al. Breaking the blue wall of silence: risk factors for experiencing police sexual misconduct among female offenders. AJPH. 2014;104(2):338–344. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odinokova V, Rusakova M, Urada LA, et al. Police sexual coercion and its association with risky sex work and substance use behaviors among female sex workers in St. Petersburg and Orenburg, Russia. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(1):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and non-Partner Sexual Violence. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore TM, Stuart GL, Meehan JC, et al. Drug abuse and aggression between intimate partners: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(2):247–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, et al. Intimate partner violence and HIV among drug-involved women: contexts linking these two epidemics - challenges and implications for prevention and treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(2–3):295–306. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.523296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devries KM, Child JC, Bacchus LJ, et al. Intimate partner violence victimization and alcohol consumption in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2014;109(3):379–391. doi: 10.1111/add.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCauley JL, Conoscenti LM, Ruggiero KJ, et al. Prevalence and correlates of drug/alcohol-facilitated and incapacitated sexual assault in a nationally representative sample of adolescent girls. J Clin Child Adolesc. 2009;38(2):295–300. doi: 10.1080/15374410802698453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gielen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JG, et al. HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma Violence Abus. 2007;8(2):178–198. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singer M. AIDS and the public health crisis of the U.S. urban poor: the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:931–948. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyatt GE, Gomez CA, Hamilton AB, et al. The intersection of gender and ethnicity in HIV risk, interventions, and prevention: new frontiers for psychology. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):247–260. doi: 10.1037/a0032744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. J Womens Health. 2011;20(7):991–1006. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stockman JK, Campbell JC, Celentano DD. Sexual violence and HIV risk behaviors among a nationally representative sample of heterosexual American women: the importance of sexual coercion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(1):136–143. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b3a8cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Browne FA, Wechsberg WM. The intersecting risks of substance use and HIV risk among substance-using South African men and women. Curr Opin Psychiatr. 2010;23(3):205–209. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833864eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weir BW, Latkin CA. Alcohol, Intercourse, and Condom Use Among Women Recently Involved in the Criminal Justice System: Findings from Integrated Global-Frequency and Event-Level Methods. AIDS Behav. 2014:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0857-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockman JK, Syvertsen JL, Robertson AM, et al. Women’s perspectives on female-initiated barrier methods for the prevention of HIV in the context of methamphetamine use and partner violence. Women Health Iss. 2014;24(4):e397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strathdee SA, Sherman SG. The role of sexual transmission of HIV infection among injection and non-injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4):iii7–iii14. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Decker MR, Miller E, McCauley HL, et al. Recent partner violence and sexual and drug-related STI/HIV risk among adolescent and young adult women attending family planning clinics. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(2):145–149. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen US states/territories, 2005. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):112–118.19. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner K, Hudson S, Latka M, et al. The effect of intimate partner violence on receptive syringe sharing among young female injection drug users: an analysis of mediation effects. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(2):217–224. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9309-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Archibald CP, et al. Social determinants predict needle-sharing behaviour among injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada. Addiction. 1997;10:1339–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Marshall CM, Rees HC, et al. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18845.22. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz R, Weber KM, Schecter GE, et al. Psychosocial correlates of gender-based violence among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in three US cities. AIDS Patient Care. 2014;28:260–267. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat M, et al. The intersections of HIV and violence: Directions for future research and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:459–478. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kouyoumdjian FG, Calzavara LM, Bondy SJ, et al. Intimate partner violence is associated with incident HIV infection in women in Uganda. AIDS. 2013;27(8):1331–1338. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835fd851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell JC, Lucea MB, Stockman JK, et al. Forced sex and HIV risk in violent relationships. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69(Suppl 1):41–44. doi: 10.1111/aji.12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh M, Rodriguez-Garcia M, Wira CR. Immunobiology of genital tract trauma: endocrine regulation of HIV acquisition in women following sexual assault or genital tract mutilation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69(Suppl 1):51–60. doi: 10.1111/aji.12027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Campbell JC. Forced sexual initiation, sexual intimate partner violence and HIV risk in women: a global review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):832–847. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott E, Hadlanda B, Werb D, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and risk for initiating injection drug use: A prospective cohort study. Prev Med. 2012;55:500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyatt GE, Myers HF, Williams JK, et al. Does a history of trauma contribute to HIV risk for women of color? AJPH. 2002;92(4):660–665. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engstrom M, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L. Childhood sexual abuse characteristics, intimate partner violence exposure, and psychological distress among women in methadone treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43(3):366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, et al. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psych. 2003;71(4):692. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Vinocur D, Chang M, Wu E. Posttraumatic stress disorder and HIV risk among poor, inner-city women receiving care in an emergency department. AJPH. 2011;101(1):120. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cavanaugh C, Hansen C, Sullivan TP. HIV sexual risk behavior among low-income women experiencing IPV: the role of posttraumatic stress disorder. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):318–327. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9623-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Rajah V, et al. Fear and violence: Raising the HIV stakes. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(2):154–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. Lancet. 2015;385(9962):55–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wirth KE, Tchetgen EJ, Silverman JG, et al. How does sex trafficking increase the risk of HIV Infection? An observational study from Southern India. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(3):232–241. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prowse KM, Logue CE, Fantasia HC, et al. Intimate partner violence and the CDC’s best-evidence HIV risk reduction interventions. Public Health Nurs. 2014;31(3):215–233. doi: 10.1111/phn.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eckhardt CM, Murphy CM, Whitaker DJ. The Effectiveness of Intervention Programs for Perpetrators and Victims of Intimate Partner Violence. Partner Abuse. 2013;4:196–231. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tiwari A, Leung WC, Leung TW, et al. A randomised controlled trial of empowerment training for Chinese abused pregnant women in Hong Kong. BJOG-Int J Obstet Gy. 2005;112(9):1249–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parker B, McFarlane J, Soeken K, et al. Testing an intervention to prevent further abuse to pregnant women. Res Nurs Health. 1999;22(1):59–66. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199902)22:1<59::aid-nur7>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilbert L, Shaw SA, Goddard-Eckrich D, et al. Project WINGS: A randomized controlled trial of a screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) service to identify and address intimate partner violence among substance-using women receiving community supervision. Crim Behav Ment Health. doi: 10.1002/cbm.1979. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tirado-Munoz J, Gilchrist G, Farre M, et al. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and advocacy interventions for women who have experienced intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Ann Med. 2014;46(8):567–586. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.941918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Manuel J, et al. An integrated relapse prevention and relationship safety intervention for women on methadone: testing short-term effects on intimate partner violence and substance use. Violence Vict. 2006;21(5):657–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson JC, Campbell JC, Farley JE. Interventions to address HIV and intimate partner violence in Sub-Saharan Africa: a review of the literature. J Assoc Nurse AIDS C. 2013;24(4):383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalichman S, Simbayi L, Vermaak R, et al. Randomized trial of a community-based alcohol-related HIV risk-reduction intervention for men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(3):270–279. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sikkema KJ, Neufeld SA, Hansen NB, et al. Integrating HIV prevention into services for abused women in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):431–439. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9620-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wechsberg WM, Luseno WK, Lam WK, et al. Substance use, sexual risk, and violence: HIV prevention intervention with sex workers in Pretoria. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(2):131–137. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Goddard-Eckrich D, et al. Efficacy of a group-based multimedia HIV prevention intervention for drug-involved women under community supervision: Project WORTH. PLoS Med. 2014;9(11):e111528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, et al. Couple-based HIV prevention in the United States: advantages, gaps, and future directions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:S98–S101. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbf407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiwatram-Negrón T, El-Bassel N. Systematic review of couple-based HIV intervention and prevention studies: advantages, gaps and future directions. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(10):1864–1887. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0827-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wray AM, Hoyt T, Gerstle M. Preliminary examination of a mutual intimate partner violence intervention among treatment-mandated couples. J Fam Psychol. 2013;27(4):664–670. doi: 10.1037/a0032912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hien DA, Jiang H, Campbell AN, et al. Do treatment improvements in PTSD severity affect substance use outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial in NIDA’s Clinical Trials Network. Am J Psychiat. 2010;167(1):95–101. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09091261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, Perez S. Cognitive behavioral treatment of PTSD in residents of battered women’s shelters: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psych. 2011;79(4):542–551. doi: 10.1037/a0023822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sikkema KJ, Wilson PA, Hansen NB, et al. Effects of a coping intervention on transmission risk behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS and a history of childhood sexual abuse. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(4):506–513. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318160d727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amaro H, Larson MJ, Zhang A, et al. Effects of trauma intervention on HIV sexual risk behaviors among women with co-occurring disorders in substance abuse treatment. J Community Psychol. 2007;35(7):895–908. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wyatt GE, Hamilton AB, Myers HF, et al. Violence prevention among HIV-positive women with histories of violence: healing women in their communities. Women Health Iss. 2011;21(6 Suppl):S255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wyatt GE, Longshore D, Chin D, et al. The efficacy of an integrated risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive women with child sexual abuse histories. AIDS and behavior. 2004 Dec;8(4):453–462. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7329-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hobbs JD, Kushner MG, Lee SS, et al. Meta-analysis of supplemental treatment for depressive and anxiety disorders in patients being treated for alcohol dependence. Am J Addiction. 2011;20(4):319–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00140.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Torchalla I, Nosen L, Rostam H, et al. Integrated treatment programs for individuals with concurrent substance use disorders and trauma experiences: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;42(1):65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Najavits LM, Hien D. Helping vulnerable populations: a comprehensive review of the treatment outcome literature on substance use disorder and PTSD. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(5):433–479. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hien DA, Campbell AN, Killeen T, et al. The impact of trauma-focused group therapy upon HIV sexual risk behaviors in the NIDA Clinical Trials Network “Women and Trauma” multi-site study. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):421–430. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9573-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chin D, Myers HF, Zhang M, et al. Who improved in a trauma intervention for HIV-positive women with child sexual abuse histories? Psychol Trauma. 2014;6(2):152–158. doi: 10.1037/a0032180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Leserman J, et al. Gender-specific effects of an augmented written emotional disclosure intervention on posttraumatic, depressive, and HIV-disease-related outcomes: a randomized, controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psych. 2013;81(2):284–298. doi: 10.1037/a0030814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meade CS, Drabkin AS, Hansen NB, et al. Reductions in alcohol and cocaine use following a group coping intervention for HIV-positive adults with childhood sexual abuse histories. Addiction. 2010;105(11):1942–1951. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sikkema KJ, Ranby KW, Meade CS, et al. Reductions in traumatic stress following a coping intervention were mediated by decreases in avoidant coping for people living with HIV/AIDS and childhood sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psych. 2013;81(2):274–283. doi: 10.1037/a0030144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hien D, Levin FR, Ruglass LR, et al. Combining Seeking Safety with Sertraline for PTSD and alcohol use disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psych. doi: 10.1037/a0038719. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brady KT, Sonne S, Anton RF, et al. Sertraline in the treatment of co-occurring alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(3):395–401. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000156129.98265.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ellsberg M, Arango DJ, Morton M, et al. Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, et al. Findings from the SASA! study: a cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of a community mobilization intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV risk in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Med. 2014;12:122. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0122-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wagman JA, Gray RH, Campbell JC, et al. Effectiveness of an integrated intimate partner violence and HIV prevention intervention in Rakai, Uganda: analysis of an intervention in an existing cluster randomised cohort. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(1):e23–33. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70344-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. Impact of Stepping Stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9551):1973–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):55–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zweig JM, Schlichter KA, Burt MR. Assisting women victims of violence who experience multiple barriers to services. Violence Against Wom. 2002;8(2):162–180. [Google Scholar]