Do androids dream of electric penguins?

In the decade since its founding in a Palo Alto garage, the name "Google" has become practically synonymous with the Internet. Thus it was that the search company's celebrated entry into the mobile market was met with significant enthusiasm from those who believed that Google would be able to use its immense resources and Internet savvy to produce a next-generation mobile product that would deliver "the cloud," in its vast entirety, into the eager hands of consumers. Some of the biggest names in the tech industry flocked to Google's banner and affirmed their support for the Open Handset Alliance, which promised to liberate the mobile masses by building a blooming garden without walls.

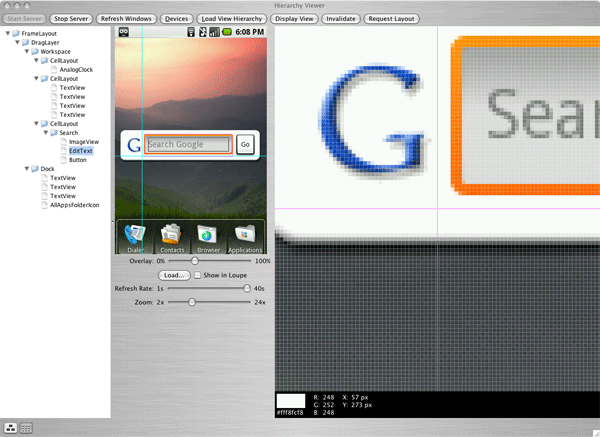

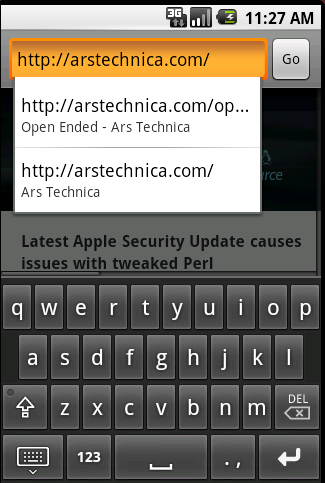

After the fanfare faded, we ended up with Android—a platform that launched with some limitations but nonetheless has significant potential. Although the first Android devices leave a lot to be desired when compared to competing products, the platform itself is evolving quickly, and it offers the advantages of openness and collaborative development. In this article we'll take a close look at the underlying technology of Android and what the platform means for developers.

Design philosophy

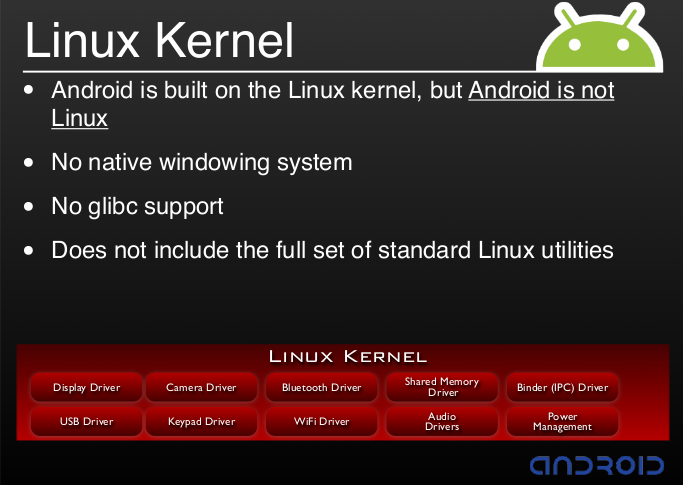

Although Android is built on top of the Linux kernel, the platform has very little in common with the conventional desktop Linux stack. In fact, during a presentation at the Google IO conference, Google engineer Patrick Brady stated unambiguously that Android is not Linux.

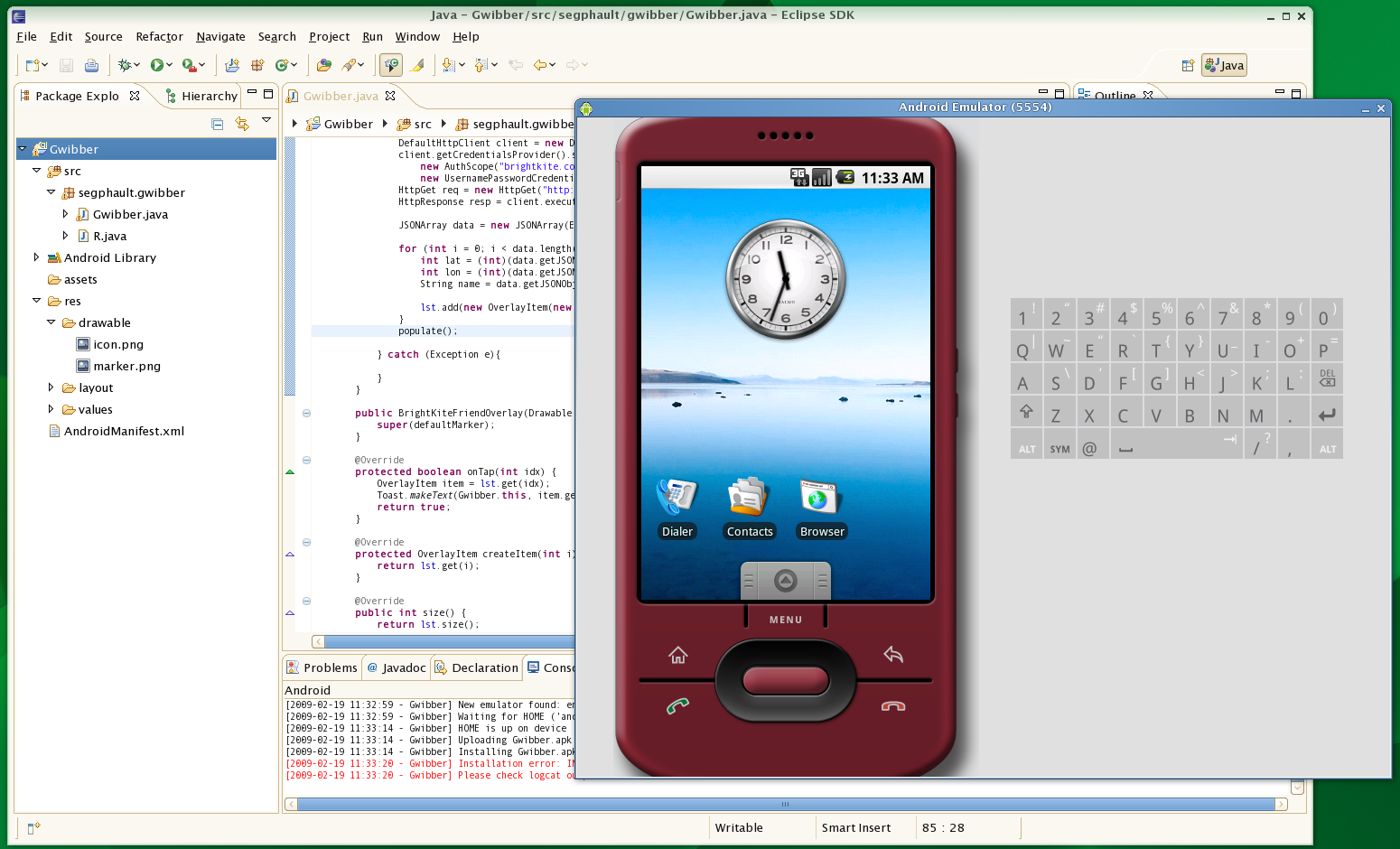

Much of the Android userspace operates within the constraints of Dalvik, Google's own custom Java virtual machine. Dalvik uses its own bytecode format called Dex, and is not compatible with J2ME or other Java runtime environments. Third-party Android applications are written in Java using Android's official APIs and widget toolkit. The Android SDK includes special compilation tools that will translate Java class files into Dex bytecode and generate an installation package that can be deployed on Android devices.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...