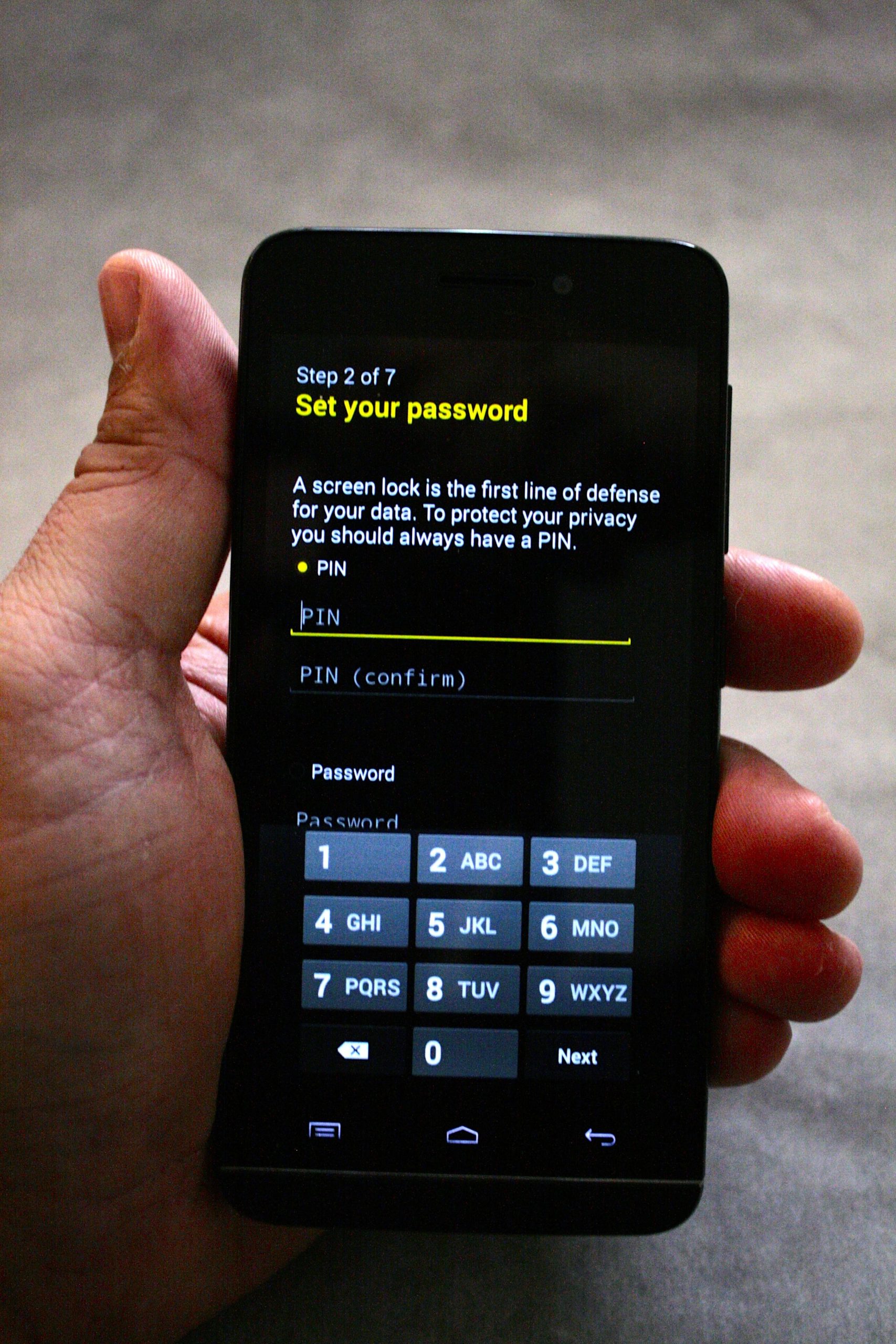

Based on some recent experience, I'm of the opinion that smartphones are about as private as a gas station bathroom. They're full of leaks, prone to surveillance, and what security they do have comes from using really awkward keys. While there are tools available to help improve the security and privacy of smartphones, they're generally intended for enterprise customers. No one has had a real one-stop solution: a smartphone pre-configured for privacy that anyone can use without being a cypherpunk.

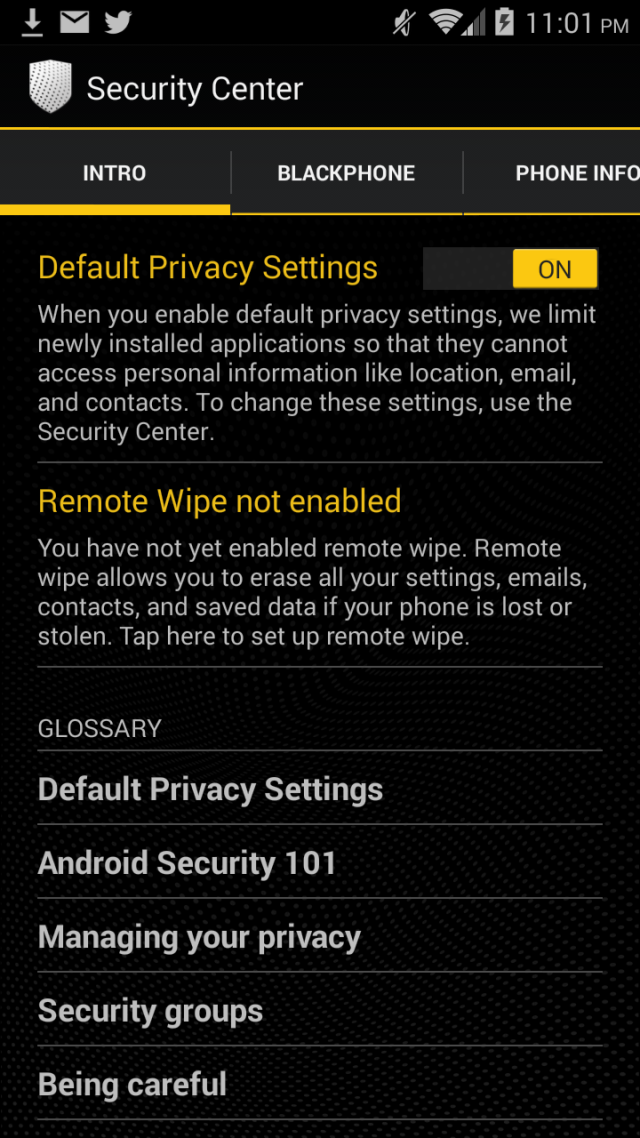

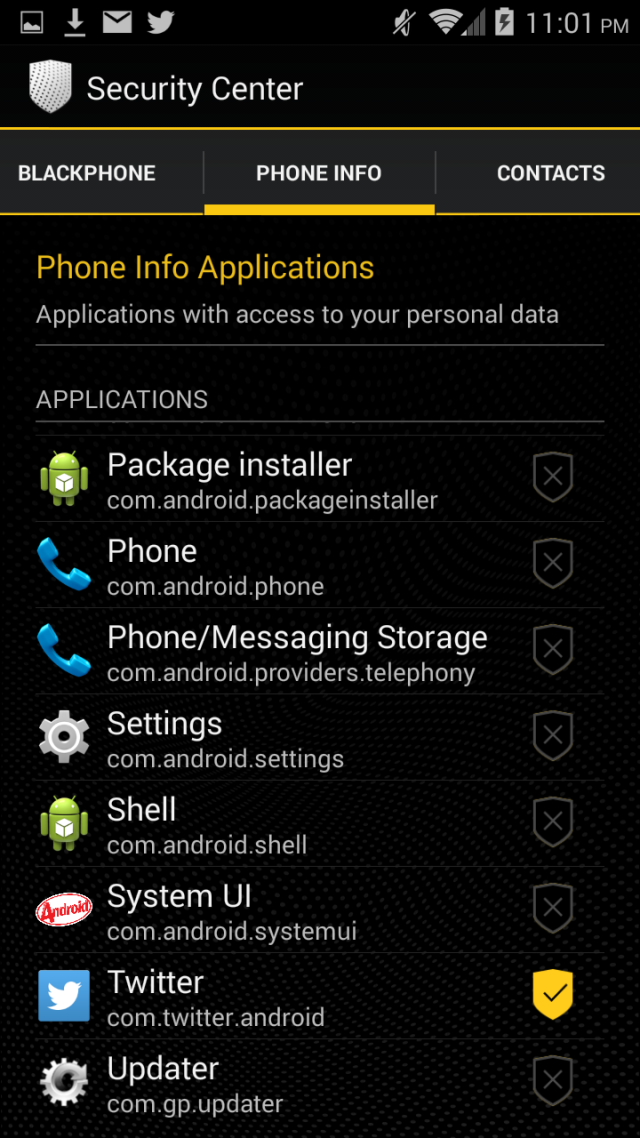

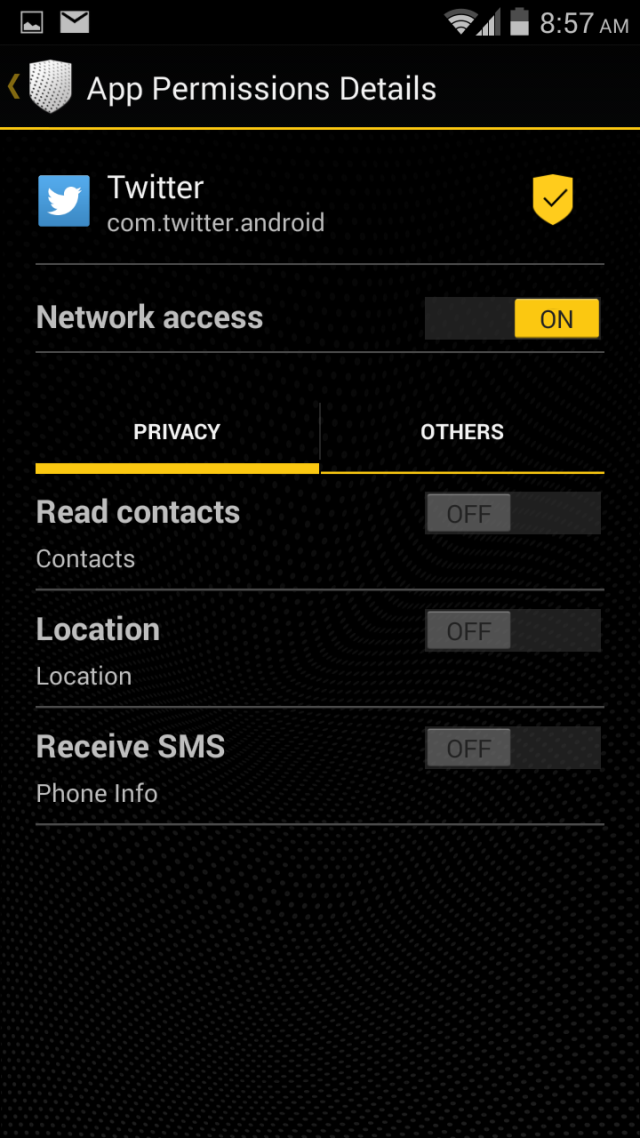

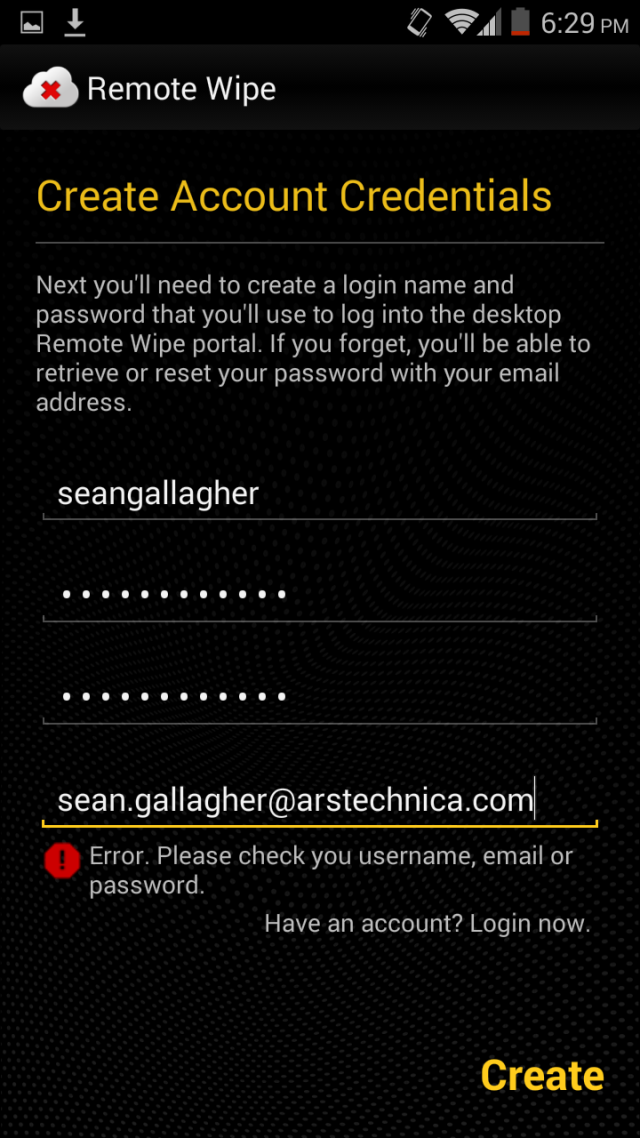

That is, until now. The Blackphone is the first consumer-grade smartphone to be built explicitly for privacy. It pulls together a collection of services and software that are intended to make covering your digital assets simple—or at least more straightforward. The product of SGP Technologies, a joint venture between the cryptographic service Silent Circle and the specialty mobile hardware manufacturer Geeksphone, the Blackphone starts shipping to customers who preordered it sometime this week. It will become available for immediate purchase online shortly afterward.

| Specs at a glance: Blackphone | |

|---|---|

| SCREEN | 4.7" IPS HD |

| OS | PrivatOS (Android 4.4 KitKat fork) |

| CPU | 2GHz quad-core Nvidia Tegra 4i |

| RAM | 1GB LPDDR3 RAM |

| GPU | Tegra 4i GPU |

| STORAGE | 16GB with MicroSD slot |

| NETWORKING | 802.11b/g/n, Bluetooth 4.0 LE, GPS |

| PORTS | Micro USB 3.0, headphones |

| CAMERA | 8MP rear camera with AF, 5MP front camera |

| SIZE | 137.6mm x 69.1mm x 8.38mm |

| WEIGHT | 119g |

| BATTERY | 2000 mAh |

| STARTING PRICE | $629 unlocked |

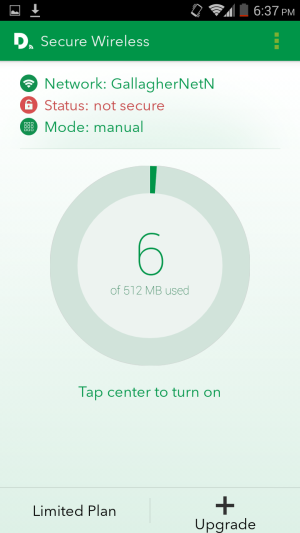

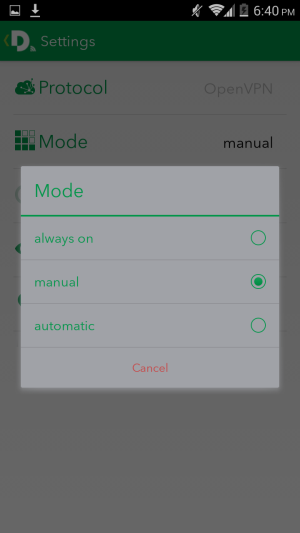

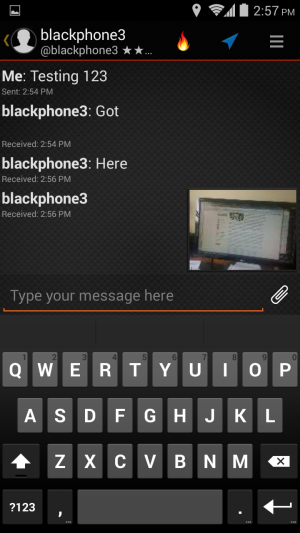

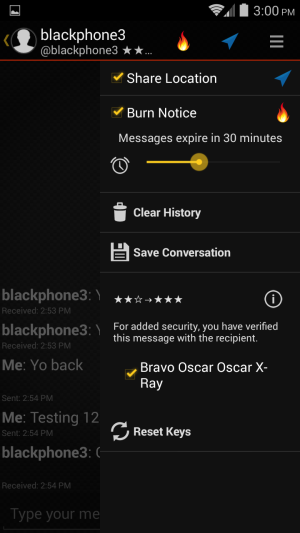

| OTHER PERKS | Bundled secure voice/video/text/file sharing, VPN service, and other security tools. |

Dan Goodin and I got an exclusive opportunity to test Blackphone for Ars Technica in advance of its commercial availability. I visited SGP Technologies’ brand new offices in National Harbor, Maryland, to pick up mine from CEO Toby Weir-Jones; Dan got his personally delivered by CTO Jon Callas in San Francisco. We had two goals in our testing. The first was to test just how secure the Blackphone is using the tools I’d put to work recently in exploring mobile device security vulnerabilities. The second was to see if Blackphone, with all its privacy armor, was ready for the masses and capable of holding its own against other consumer handsets.

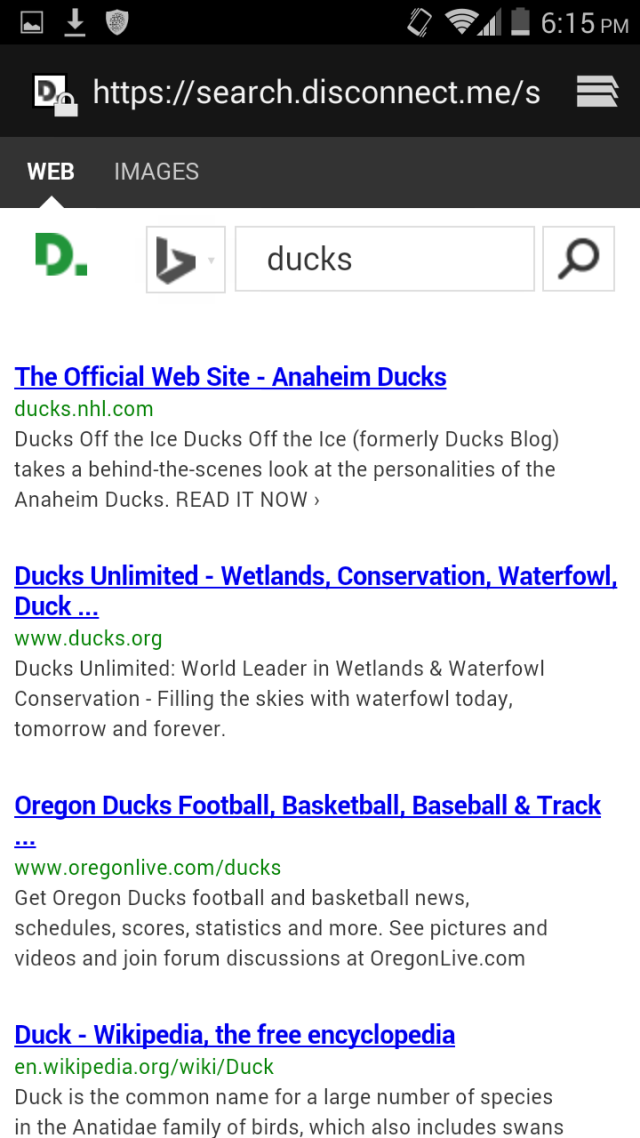

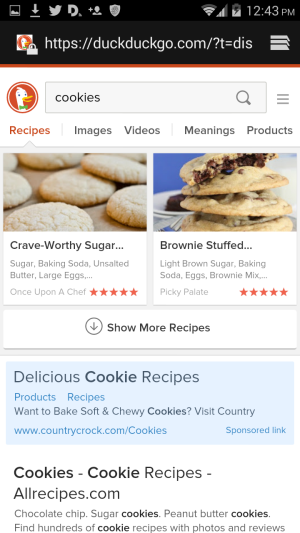

We found that Blackphone lives up to its privacy hype. During our testing in a number of scenarios, there was little if any data leakage that would give any third-party observer anything usable in terms of private information.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...